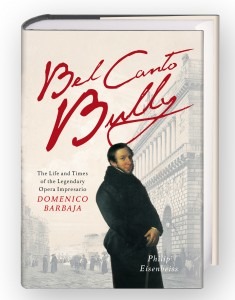

He was a drunkard, a nearly illiterate loudmouth, and a serial womanizer with a natural gift for seemingly endless self-promotion. He strong-armed and bullied his way to personal fame and fortune by building a gaming syndicate, and intuitively and prosperously navigated the treacherous political and cultural landscape of his day. Yet, he also collaborated and helped to discover some of the greatest operatic composers active during the ‘bel canto’ period, including Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Saverio Mercadante. Efficient and profit-orientated he managed a stable of legendary opera singers and dancers, and he certainly revolutionized the way many Europeans enjoyed music and opera. His name was Domenico Barbaja (1777-1841), and he is the subject of Philip Eisenbeiss’ engaging, entertaining and highly informative book Bel Canto Bully.

He was a drunkard, a nearly illiterate loudmouth, and a serial womanizer with a natural gift for seemingly endless self-promotion. He strong-armed and bullied his way to personal fame and fortune by building a gaming syndicate, and intuitively and prosperously navigated the treacherous political and cultural landscape of his day. Yet, he also collaborated and helped to discover some of the greatest operatic composers active during the ‘bel canto’ period, including Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Saverio Mercadante. Efficient and profit-orientated he managed a stable of legendary opera singers and dancers, and he certainly revolutionized the way many Europeans enjoyed music and opera. His name was Domenico Barbaja (1777-1841), and he is the subject of Philip Eisenbeiss’ engaging, entertaining and highly informative book Bel Canto Bully.

From the very onset, Eisenbeiss suggests that he is not presenting a work of academic scholarship nor specialist musicological research, and that is clearly one of the strengths of this publication. This is no dry textbook, but fluently written prose that affords us a unique glimpse into the world behind the operatic curtain. Whether Barbaja is paying off the local police force, seducing the Spanish prima donna Isabella Colbran or locking the famously tardy Rossini into his apartment until he has completed the musical score, Eisenbeiss keeps the reader engaged and in suspense throughout. In fact, we can’t wait to find out what political schemes, romantic intrigues or operatic projects that scoundrel Barbaja will engage with next!

From the very onset, Eisenbeiss suggests that he is not presenting a work of academic scholarship nor specialist musicological research, and that is clearly one of the strengths of this publication. This is no dry textbook, but fluently written prose that affords us a unique glimpse into the world behind the operatic curtain. Whether Barbaja is paying off the local police force, seducing the Spanish prima donna Isabella Colbran or locking the famously tardy Rossini into his apartment until he has completed the musical score, Eisenbeiss keeps the reader engaged and in suspense throughout. In fact, we can’t wait to find out what political schemes, romantic intrigues or operatic projects that scoundrel Barbaja will engage with next!

In a sense, it’s easy because Barbaja is a character we all love to hate! While rags to riches stories endlessly fascinate us, his tactics and gnarly business practices are occasionally at bit too close for comfort. Entertaining prose and colorful personalities none withstanding, the book is full of important and valuable details about the role and function of a promoter/producer navigating the tumultuous political, cultural, and social environment of the 19th century. Above all, Barbaja not merely collaborated and commissioned unforgettable works from the greatest composers of the ‘bel canto,’ he was also partly responsible for turning opera into the premier art form in the second half of the 19th century. His efforts in Naples involving the young Rossini made the two royal stages the most admired operatic performing venues in Europe. He certainly also made an impression in Vienna—although the opera Fierrabras he commissioned from Franz Schubert failed to be performed—and he eventually helped to turn Milan into one of the leading European stages. Clearly not everything Barbaja touched turned into gold, but it would be of enormous interest to further explore the cantatas, hymns, ballets and other compositions he commissioned and inspired. Philip Eisenbeiss has provided us with a compelling look behind the operatic curtain, and Naxos Records have issued a companion CD to musically illustrate Barbaja’s extraordinary legacy; what a delightful combination!

In a sense, it’s easy because Barbaja is a character we all love to hate! While rags to riches stories endlessly fascinate us, his tactics and gnarly business practices are occasionally at bit too close for comfort. Entertaining prose and colorful personalities none withstanding, the book is full of important and valuable details about the role and function of a promoter/producer navigating the tumultuous political, cultural, and social environment of the 19th century. Above all, Barbaja not merely collaborated and commissioned unforgettable works from the greatest composers of the ‘bel canto,’ he was also partly responsible for turning opera into the premier art form in the second half of the 19th century. His efforts in Naples involving the young Rossini made the two royal stages the most admired operatic performing venues in Europe. He certainly also made an impression in Vienna—although the opera Fierrabras he commissioned from Franz Schubert failed to be performed—and he eventually helped to turn Milan into one of the leading European stages. Clearly not everything Barbaja touched turned into gold, but it would be of enormous interest to further explore the cantatas, hymns, ballets and other compositions he commissioned and inspired. Philip Eisenbeiss has provided us with a compelling look behind the operatic curtain, and Naxos Records have issued a companion CD to musically illustrate Barbaja’s extraordinary legacy; what a delightful combination!

Gioachino Rossini: Maometto, Act II, “Non temer d’un basso affetto”

Vincenzo Bellini: Il pirata, Act 1, “Per te di vane lagrime”

Gaetono Donizetti: Roberto Devereux, Act III, “Quel sangue versato al cielo s’innalza”