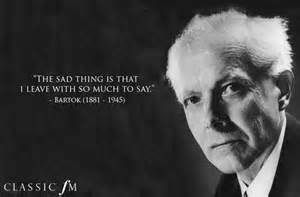

Béla Bartók my father’s Hungarian countryman, is considered a composer of profound influence in the 20th century. If you haven’t yet met him I am delighted to share some of my favorite works with you.

Béla Bartók my father’s Hungarian countryman, is considered a composer of profound influence in the 20th century. If you haven’t yet met him I am delighted to share some of my favorite works with you.

Béla Bartók was born in 1881 to a musical family. His father was the director of an agricultural school, but at the same time he was a talented amateur musician playing both the piano and the cello. Bartók Senior founded a music society and an amateur orchestra in his town. Bartók’s mother who also played the piano began teaching Béla. By the time he was five years old he could play 40 piano pieces. His debut as a pianist occurred when he was eleven but by then he had several compositions under his belt.

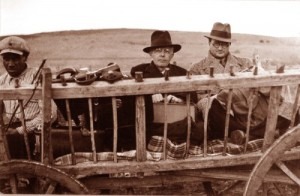

Bartók with peasants

Bartók plays the piano Allegro Barbaro

By 1907 Bartók was teaching at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest along with his lifelong fiend Zoltán Kodály both of whom my father encountered. Interestingly, Bartók didn’t teach composition. His philosophy was that one couldn’t teach composing.

Bartók in Turkey

Janos Starker Rumanian Folk Dances

Bartók’s music is infused with these folk tunes and experimental harmonies which created modern, Hungarian music. His scientific classification of folk music is often considered the beginning of ethnomusicology.

A Hungarian peasant singing

As the political situation of Hungary became more and more unsettled in the mid-1930s, Bartók produced prodigiously, some of his most important works, despite his staunch stance against fascism—Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion the Contrasts for violin, clarinet, and piano, the Violin Concerto as well as his Sixth String Quartet. When Nazi Germany annexed Austria in 1938, he decided he must leave Hungary. After his mother’s death in 1939 Bartók moved to the United States. It was tough emotionally and physically.

Columbia University appointed Bartók to a one-year research position in 1941. But his ill health prevented him from composing anything from 1940 to 1942 and he was unable to perform publicly. Bartók barely eked out a living. This was compounded by the fact that he was a shy and very proud man refusing financial help from friends and colleagues.

Fortunately, he was able to resume composing producing two of his best-loved works. Bartók got assistance from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers and several important commissions— Serge Koussevitzky commissioned The Concerto for Orchestra and Yehudi Menuhin commissioned the solo Violin Sonata. The Viola Concerto, commissioned by famed violist William Primrose, was left unfinished subsequently completed by Tibor Serly, one of Bartók’s pupils. Bartók was working on his Third Piano Concerto, composed for his wife, until a few days before he died of leukemia Sept. 26, 1945. The last 17 measures were still incomplete.

Rhapsody No. 1, BB 94a

Joseph Szigeti and Béla Bartók

Personally I have loved to play his music. One of my favorite pieces to play is his Rumanian Folk Dances. His Hungarian Rhapsody No. 1 is a work I grew up hearing my father play. In these works you can hear the folk elements clearly. Such fun to play too!

A csodalatos mandarin koncertszvit (The Miraculous Mandarin Suite), Op. 19, BB 82

The Concerto For Orchestra is standard repertory for every orchestra and a huge romantic tour de force. The Music for Strings Percussion and Celeste and the ballet Miraculous Mandarin—a contemporary story of prostitution, robbery, sexuality and murder, somewhat in the primitive vein of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring— though much more challenging for both the performers to play and audience members to listen to, are favorite masterworks. I dare you to sit still during the last three minutes of the piece!