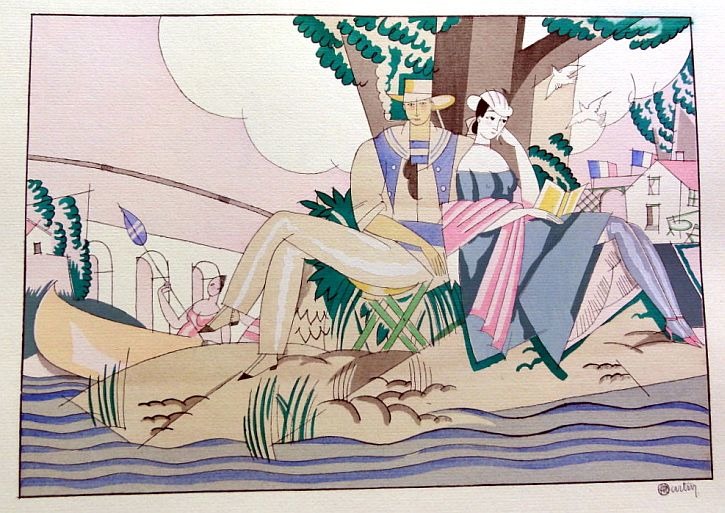

Recently, I came across a composition entitled Three Boneless Preludes for a Dog. With a name like that, it was instantly clear that it could only have come from the pen of Erik Satie. But it was still rather surprising to learn that Satie composed these piano miniatures as love songs for Suzanne Valadon. He performed the pieces in the studios of his friends, with Valadon settled at his feet and sporting a delicious necklace of sausages! Satie first met Suzanne Valadon on 14 January 1893 at the “Auberge du Clou,” a boisterous and inexpensive nightclub, where he had taken a job as the second pianist. She was sitting at a corner table with her current lover when Satie joined them. Within minutes he was in love, and within hours he proposed. She immediately agreed, but since it was 3 in the morning, it was “an impossible time to get to the mairie.” So they retired to opposite rooms in 6 rue Cortot and commenced a torrid affair that lasted six months.

Recently, I came across a composition entitled Three Boneless Preludes for a Dog. With a name like that, it was instantly clear that it could only have come from the pen of Erik Satie. But it was still rather surprising to learn that Satie composed these piano miniatures as love songs for Suzanne Valadon. He performed the pieces in the studios of his friends, with Valadon settled at his feet and sporting a delicious necklace of sausages! Satie first met Suzanne Valadon on 14 January 1893 at the “Auberge du Clou,” a boisterous and inexpensive nightclub, where he had taken a job as the second pianist. She was sitting at a corner table with her current lover when Satie joined them. Within minutes he was in love, and within hours he proposed. She immediately agreed, but since it was 3 in the morning, it was “an impossible time to get to the mairie.” So they retired to opposite rooms in 6 rue Cortot and commenced a torrid affair that lasted six months.

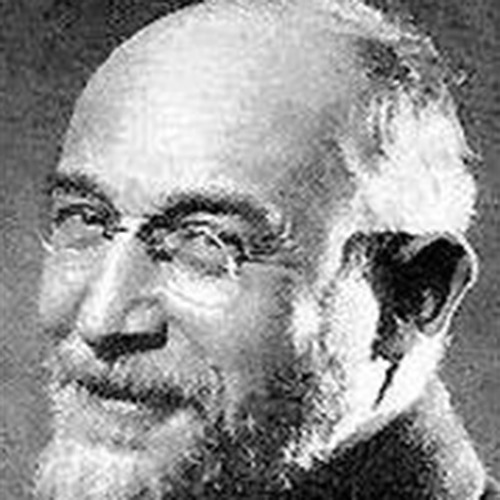

Satie came from a comfortable bourgeois background and received his first music lessons from a local Parisian organist. He started a little publishing venture, issuing salon compositions by his stepmother and himself. By 1879 Satie entered the Paris Conservatoire, but was soon labeled “the laziest student in the world.” His piano technique was described as “insignificant and laborious, and entirely worthless.” Satie was unceremoniously expelled after a couple of years, but at the petition of his father, readmitted soon thereafter. After a couple of months he was expelled again, and counseled to take up military service. That career was also short-lived, as he deliberately infecting himself with bronchitis to escape the army. Penniless, but full of youthful exuberance and eccentricity he took up lodgings in Montmartre, rubbing shoulders with the artistic and literary elite.

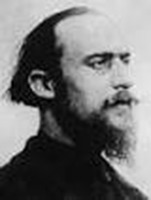

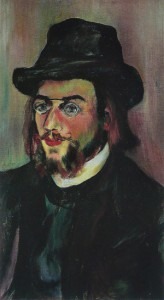

Suzanne Valadon was only a year older than Satie but no less eccentric. Daughter of an unmarried laundress, she left school at age nine to work in a clothing sweatshop. Other occasional employments included waitressing, selling peanuts from a pushcart, and grooming in a livery stable. She even joined the circus at age fifteen, but a fall from the trapeze sadly ended that particular career ambition. So she became an artist’s model, sitting for Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes. While Toulouse-Lautrec gave her painting lessons, Renoir and Chavannes gave her physical comfort and a son. An unbridled free spirit, she “wore a corsage of carrots, kept a goat at her studio to eat her bad drawings, and fed caviar to her ‘good Catholic’ cats on Fridays.” She painted portraits, flowers and landscapes, but was best known for her female nudes. Even Edgar Degas was thoroughly impressed by her paintings, and even arranged for exhibitions of her works.

Suzanne Valadon was only a year older than Satie but no less eccentric. Daughter of an unmarried laundress, she left school at age nine to work in a clothing sweatshop. Other occasional employments included waitressing, selling peanuts from a pushcart, and grooming in a livery stable. She even joined the circus at age fifteen, but a fall from the trapeze sadly ended that particular career ambition. So she became an artist’s model, sitting for Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes. While Toulouse-Lautrec gave her painting lessons, Renoir and Chavannes gave her physical comfort and a son. An unbridled free spirit, she “wore a corsage of carrots, kept a goat at her studio to eat her bad drawings, and fed caviar to her ‘good Catholic’ cats on Fridays.” She painted portraits, flowers and landscapes, but was best known for her female nudes. Even Edgar Degas was thoroughly impressed by her paintings, and even arranged for exhibitions of her works.

Among her most famous works is a portrait of Erik Satie, dating from the very beginnings of their stormy affair. Dominated by Satie’s head, the painting reveals “a methodical frankness close to brutality. If she has rendered his powerful yet sensitive bohemian presence, she has not hidden an aloofness and judgmental quality.” Valadon painted Satie, and Satie painted Valadon. The two works hung together and were found in Satie’s room after his death. Satie was obsessed with Valadon, tenderly calling her his “Biqui” and composed a four-measure piece entitled Bonjour, Biqui, Bonjour as a tribute to their romance. He wrote impassioned letters, praising “her whole being, her lovely eyes, gentle hands and tiny feet.” For a while, Valadon became entirely domestic, cleaned his room, cooked his meals and darned his socks. However, after six months she abruptly packed her things and moved away. Satie wrote to his brother, “I shall have great difficulty in regaining possession of myself, loving this little person as I have loved her; she was able to take all of me. Time will do what at this moment I cannot do.” He composed Vexations to give voice to his emotions and his broken heart, and regretful adding “she just had too many things on her mind to get married.” He would continue to write her passionate letters over the next 30 years, as Suzanne Valadon’s departure left him “with nothing but an icy loneliness that fills the head with emptiness and the heart with sadness.” As far as we know, Suzanne Valadon was Satie’s only love affair!

Among her most famous works is a portrait of Erik Satie, dating from the very beginnings of their stormy affair. Dominated by Satie’s head, the painting reveals “a methodical frankness close to brutality. If she has rendered his powerful yet sensitive bohemian presence, she has not hidden an aloofness and judgmental quality.” Valadon painted Satie, and Satie painted Valadon. The two works hung together and were found in Satie’s room after his death. Satie was obsessed with Valadon, tenderly calling her his “Biqui” and composed a four-measure piece entitled Bonjour, Biqui, Bonjour as a tribute to their romance. He wrote impassioned letters, praising “her whole being, her lovely eyes, gentle hands and tiny feet.” For a while, Valadon became entirely domestic, cleaned his room, cooked his meals and darned his socks. However, after six months she abruptly packed her things and moved away. Satie wrote to his brother, “I shall have great difficulty in regaining possession of myself, loving this little person as I have loved her; she was able to take all of me. Time will do what at this moment I cannot do.” He composed Vexations to give voice to his emotions and his broken heart, and regretful adding “she just had too many things on her mind to get married.” He would continue to write her passionate letters over the next 30 years, as Suzanne Valadon’s departure left him “with nothing but an icy loneliness that fills the head with emptiness and the heart with sadness.” As far as we know, Suzanne Valadon was Satie’s only love affair!

Eric Satie: Preludes pour un chien

You May Also Like

-

Erik Satie: “Like a nightingale with toothache” Like many composers past and present, Erik Satie was in constant financial troubles. To escape his creditors he frequently changed his lodgings, ending up in a tiny room at 6 rue Cortot in the spring of 1890.

Erik Satie: “Like a nightingale with toothache” Like many composers past and present, Erik Satie was in constant financial troubles. To escape his creditors he frequently changed his lodgings, ending up in a tiny room at 6 rue Cortot in the spring of 1890. -

“Before I compose a piece, I walk around it several times” For Erik Satie, dance, theatre and cabaret music run as virtually continuous threads throughout his life.

“Before I compose a piece, I walk around it several times” For Erik Satie, dance, theatre and cabaret music run as virtually continuous threads throughout his life. -

Erik Satie “Memoirs of an Amnesiac”

Erik Satie “Memoirs of an Amnesiac”

When eccentricity and classical music are used in the same sentence, Erik Satie (1866-1925) immediately comes to mind. -

Georges Braque and Erik Satie – A Musical Friendship Violins, guitars, mandolins, music sheets and references to classical composers are very much part of Braque’s oeuvre...

Georges Braque and Erik Satie – A Musical Friendship Violins, guitars, mandolins, music sheets and references to classical composers are very much part of Braque’s oeuvre...

More Love

- Untangling Hearts

Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang What happens when two brilliant musicians fall in love - and then fall apart? -

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music?