Does an audience have a right to boo? Or is it boorish, arrogant and rude? There is a long tradition of riots in the concert hall complete with hissing and catcalls and throwing food—tomatoes, radishes (in the case of Maria Callas) turnips (Renata Scotto) and even punches. As far back as the 1600’s, organized groups of professional applauders were hired to incite the audience—who clapped, laughed after jokes in the drama, or cried when tears were in order. Claques were common and considered essential. By the 1830’s claque behavior was well established and any performance was risky business without a claque! Some groups engaged in extortion— they were of course entitled to free tickets. Some demanded a bribe from the performers, so that the artist could ensure that they wouldn’t be heckled during the performance. Claques tried to out-scream each other in favor of one or another composer or style.

Does an audience have a right to boo? Or is it boorish, arrogant and rude? There is a long tradition of riots in the concert hall complete with hissing and catcalls and throwing food—tomatoes, radishes (in the case of Maria Callas) turnips (Renata Scotto) and even punches. As far back as the 1600’s, organized groups of professional applauders were hired to incite the audience—who clapped, laughed after jokes in the drama, or cried when tears were in order. Claques were common and considered essential. By the 1830’s claque behavior was well established and any performance was risky business without a claque! Some groups engaged in extortion— they were of course entitled to free tickets. Some demanded a bribe from the performers, so that the artist could ensure that they wouldn’t be heckled during the performance. Claques tried to out-scream each other in favor of one or another composer or style.

They did their damage. Composer Richard Wagner withdrew his Tannhäuser after Parisian opera society’s Jockey Club claque interrupted the first performance of his work. One of my favorite performances of the Overture is Klaus Tennstedt conducting the London Philharmonic. Think about the riot at the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, and the so-called Skandalkonzert of 1913 Vienna when Alban Berg’s Altenberg Lieder could not be heard above the booing. Audience members were injured when the evening degenerated and a fight broke out. More recent disruptions ensued when Steve Reich’s Four Organs was greeted with derisive applause and yelling at Carnegie Hall.

Nowhere is the booing tradition so ensconced than in Italy. Rossini’s The Barber of Seville was booed at its premiere, and so was Verdi’s La Traviata.

In fact, at the famed opera house La Scala, the boo-ers (the loggionisti)—audience members who sit in the cheap seats in the rafters—feel entitled to express their opinions. After all, they are knowledgeable opera patrons who show up with scores to the opera, unlike the people who are able to buy expensive seats and attend the opera to be seen.

In fact, at the famed opera house La Scala, the boo-ers (the loggionisti)—audience members who sit in the cheap seats in the rafters—feel entitled to express their opinions. After all, they are knowledgeable opera patrons who show up with scores to the opera, unlike the people who are able to buy expensive seats and attend the opera to be seen.

Today audiences tend to be polite but there have been notable exceptions. The 2012 Royal Opera performance of Rusalka, Dvořák’s opera based on fairy tales with similar themes as Hans Christian Andersen’s 19th century fable The Little Mermaid kindled vociferous booing. Patrons found the modern interpretation offensive. It portrayed the heroine as a prostitute in a squalid brothel.

LA Opera Die Walküre à la Star Wars

The Los Angeles Opera’s production of Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen in 2010 featured a stellar cast that included tenor Placido Domingo as Siegmund and German soprano Anja Kampe as Sieglinde in a bizarre production by the German director Achim Freyer. The singers and orchestra received an enormous ovation after the first performance of Die Walküre, but the Director, who staged the production, was loudly booed. Many audience members thought the dramatization was ridiculous and distracting with its odd two-toned futuristic costumes and a Ride of the Valkyries battle with Star Wars-like laser-spears.

Other theater directors are following suit staging operas in modern times with avant-guard props and themes. This occurred at the Met during the premiere of Bellini’s 19th-century opera “La Sonnambula” in 2000, produced by Mary Zimmerman, noted experimental theater director. The setting was catapulted to modern day New York. The singers wore leather and carried cellphones. The audience was angry and they booed.

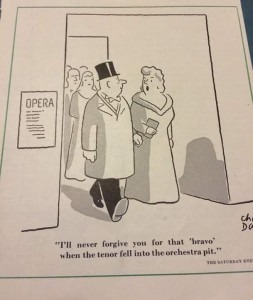

Some conductors have put their foot down. Riccardo Muti was booed at La Scala in 2000. He turned around and scolded the loggionisti telling them “that an opera house is not a circus”. In 1982 the Met audience booed tenor Carlo Bini. He had been a quick replacement for the ailing star Domingo. The conductor, Giuseppe Patane, was incensed. He stopped conducting and yelled, “Shame on you. At least have some respect for Ponchielli! If you don’t like it, don’t clap.”

Some conductors have put their foot down. Riccardo Muti was booed at La Scala in 2000. He turned around and scolded the loggionisti telling them “that an opera house is not a circus”. In 1982 the Met audience booed tenor Carlo Bini. He had been a quick replacement for the ailing star Domingo. The conductor, Giuseppe Patane, was incensed. He stopped conducting and yelled, “Shame on you. At least have some respect for Ponchielli! If you don’t like it, don’t clap.”

Are the audiences of today waking up from complacency? What’s wrong with a little passion from the mezzanine to show they are really listening? Booing can jolt audiences into being more engaged with the drama. Perhaps you agree with the opinion that without the possibility of “booing” a performance, applause or a standing ovation comes to mean nothing.

The ovation that shook the world of opera has to be the mesmerizing last performance of soprano Leontyne Price. Her farewell still sends chills down my spine. Before the historic aria, the audience at the Metropolitan Opera House was absolutely hushed. Price’s rendition so heart-rending and poignant received an almost hysterical audience ovation afterwards that went on for many emotional minutes.

Maestro Toscanini and composer-conductor Gustav Mahler intervened with disapproval of claques introducing proper concert etiquette. Perhaps the claque is the precursor to our present day “laugh-tracks.”

Tannhäuser overture with Klaus Tennstedt