Watching cattle graze in their natural environment is one of life’s bucolic pleasures. As natural herbivores, they eat a lot of grasses and hay. Yet in commercial farming, various feeds are used, which may contain ingredients such as antibiotics, hormones, pesticides, fertilizers. In addition, feeding them protein supplements such as meat, bone and fishmeal produced from the ground and cooked leftovers from the slaughtering process, as well as from the carcasses of sick and injured animals used to be a widespread practice. You’ve got to scratch your head on this one. Turning a natural herbivore into a protein-munching cannibal seems the height of human folly.

Watching cattle graze in their natural environment is one of life’s bucolic pleasures. As natural herbivores, they eat a lot of grasses and hay. Yet in commercial farming, various feeds are used, which may contain ingredients such as antibiotics, hormones, pesticides, fertilizers. In addition, feeding them protein supplements such as meat, bone and fishmeal produced from the ground and cooked leftovers from the slaughtering process, as well as from the carcasses of sick and injured animals used to be a widespread practice. You’ve got to scratch your head on this one. Turning a natural herbivore into a protein-munching cannibal seems the height of human folly.

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE)

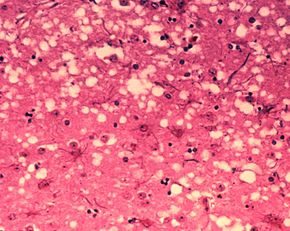

Unsurprisingly, it led to a horrible neurodegenerative disease in cattle called bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease. This disease is not caused by a virus, but by a misfolded protein, known as a prion, and it is not destroyed by heat treatment. When humans come in contact with contaminated butchery equipment or eat infected beef or blood products, it results in Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. In essence, brain cells begin to die in massive number leading to microscopic holes in the brain. The patient experiences psychiatric problems, behavioral changes, painful sensations, degeneration of physical and mental abilities, coma, and ultimately death. Average life expectancy following the onset of symptoms is 13 months, and treatment involves supportive care. Maybe Edvard Grieg should have thought twice before calling the cows to come home?

Edvard Grieg: 2 Nordic Melodies, Op. 63 – No. 2a. Kulok (Cow Call) (Camerata Oslo; Stephan Barratt-Due, cond.)

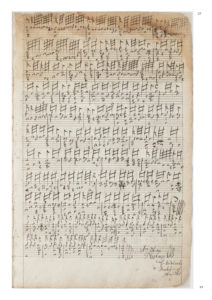

Lute Intabulation

Lute music was all the rage during the Renaissance. Much of the instrumental music during that period was written for that particular instrument, and a good education simply meant mastery of the instrument. With the advent of printing, independent instrumental music not connected to vocal music was proliferating, but vocal, polyphonic music was happily performed on the lute. Vocal music was intabulated, that is, written in shorthand musical code so it could be performed on the lute. Sometimes voices were left out of difficult vocal parts and adorned with ornaments and trills. Bálint Bakfark (1526–30 to 15 or 22 August 1576) was a Hungarian lutenist and composer, renowned as a virtuoso on the instrument. He traveled to Italy and France, and was eventually employed as court lutenist by Sigismund II Augustus. He still managed to travel around Europe and his fame increased exponentially. Bakfark died during a plague epidemic in 1576 in Padua, and as was common practice at the time, all his possessions were destroyed by fire. As such, the vast majority of his music has been lost. However, his intabulation of the highly popular folk song “Black Cow” has luckily survived.

Bakfark: Czarna krowa (Black Cow) (Canor Anticus)

Alexander Tcherepnin

When Alexander Tcherepnin (1899-1977) settled in Paris, he completed his studies with Vidal and Isidor Philipp, head of the piano department at the Paris Conservatory. In addition, he became associated with a group of composers that included Bohuslav Martinů, Marcel Mihalovici and Conrad Beck. He also was a frequent visitor to the salon of Madame Mathilde Amos, a famous patroness of the arts in Paris. Widow of a Lorraine brewer, her salon helped to start the “Roaring Twenties of Montparnasse.” Apparently, Madame Amos had a vast collection of paintings by Raoul Dufy, and an enormous showcase holding various figurines. In his Le monde en vitrine, Op. 75, Tcherepnin musically depicted some of these figurines. “The first movement,” the composer writes, “is inspired by a group of miniature greyhounds in glass, which in the show-case stands next to a massive porcelain cow. The greyhounds are full of action, whilst the cow is placid. This contrast inspired me deeply. How often in life is our enthusiasm thwarted by something as placid as a cow!”

Alexander Tcherepnin: Le Monde en Vitrine, Op. 75 – I. The Greyhounds and the Cow (Giorgio Koukl, piano)

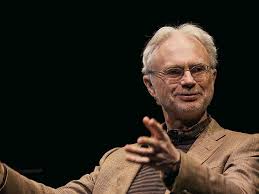

John Adams

BSE and Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease did not only have a devastating impact on cattle and human beings. It also caused billions and billions of dollars worth of damage to the economy. A North American case was first reported in Canada, and beef exports were severely restricted. With this frightening condition said to have originated in the United Kingdom, composer John Adams (b. 1947) decided to musically encode his distaste. As he writes in his notes for the second movement of Gnarly Buttons, “The Hoedown (Mad Cow) is normally associated with horses. This version of the traditional Western hoedown addresses the fault lines of international commerce from a distinctly American perspective.” Such enigmatic comments about this movement may in fact refer to the original performers being British—the composition for solo clarinet and chamber ensemble was premiered at Queen Elizabeth Hall in London with the London Sinfonietta—at a time when Britain was in the clutches of the BSE or mad cow crisis.

John Adams: Gnarly Buttons – II. Hoedown (Mad Cow) (Elizabeth Jordan, clarinet; Northern Chamber Orchestra; Stephen Barlow, cond.)