“Never play faster than you can think”

“Never play faster than you can think”

This well-known maxim by pianist, teacher and composer Tobias Matthay has a relevance both in day-to-day practice, and also in performance. When we practice, in our eagerness to move on to a new section or movement, we may rush ahead without taking the time to fully absorb what we are learning. There is also the habit, particularly among young students, of playing everything too fast without taking the time to think. And how often have we played a piece marked Allegro and taken it at such a lick that the fingers work ahead of the brain and we end up in an unholy muddle?

Music, like speech, needs to “breathe”. This is a perfect analogy, not least because the melodic line in piano music can, and should, be approached as sung line. On a practical level, where a singer might take a breath marks the natural end and beginning of a phrase, but singing also lends shape to music: the human voice has a natural rise and fall and cadence, something we should strive to imitate at the piano. Other physical gestures and body language can also help to enhance both sound and mood: the wistful lifting of the fingers off the keyboard to allow the music to float around the room; the speed and angle of attack and lift off, to suggest different moods; differentiation between the various “layers” of sound/melodic line within a piece; “implied dynamics” rather than actual volume of sound (for example, a fortissimo marking in Schubert or Chopin can be suggestive or psychological rather than actual).

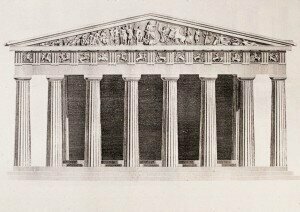

In his book The Craft of Piano Playing, Canadian pianist and professor Alan Fraser talks about “entasis” in music, the careful distortion of pulse, melodic shape or harmonic colour to enhance innate musical content. The term, derived from architectural language, means a slightly convex curve given to a column, pier or similar structure to correct the illusion of concavity created by a straight shaft. ‘Aural entasis’, Fraser says, can, just as in architecture, create the illusion of greater lengthening or shortening, thus highlighting the contours of the music, and should suffuse every bar we play (note: not to be confused with Rubato, which is a more deliberate action in music). At the simplest level, this can be the increase in dynamic level as the music ascends the register, and a softening the lower the music descends. It can also refer to rhythmic elements, such as waiting an instant longer before sounding a syncopation, or the shortening of the first part of a dotted rhythm to increase vitality, emphasis and drama. Waiting a microsecond longer before playing the next note in a sequence offers a wonderful sense of delayed gratification to the listener, especially if combined with ambiguous harmonic shifts, such as in Chopin’s First Ballade, or at the end of his Opus 62 Nocturnes, which have the most mesmerizing harmonies. No two beats will ever last exactly the same amount of time: only a metronome has this exacting regularity, and music that is played with such a rigid pulse will never sound natural.

Chopin: Nocturne No. 17 in B Major, Op. 62, No. 1

It is hard to teach such subtle elements as these, which are often very personal to the individual performer, but a good performer will employ ‘entasis’ almost unconsciously, thus giving the music its human, ‘speaking’ and ‘breathing’ qualities. Music which lacks these qualities can sound static, flat and dull, no matter how well it is played technically, and audiences will soon lose interest because mechanical music lacks a spiritual quality: as Aristotle observed “sameness of incident soon produces satiety” (Poetics XXIV). Mistakes, even very small slips or smudges, can also be far more obvious in music that is played without ‘entasis’, and the requirement to play with extreme accuracy, both of pitch and metre, is the cause of much performance anxiety amongst musicians.

Of course, too much ‘entasis’ may produce chaos in music, which listeners can find confusing and uncomfortable. To achieve a natural sense of pulse in music, drill the piece with the metronome until it is almost too fast, and then allow it to relax as you sense its metre from within, as you might your own heartbeat. The musical beat must fluctuate according to the emotional content of the music – just as the human heartbeat fluctuates at times of stress, excitement, contentment or relaxation. Remember, true musical perfection is in the soul of the listener, rather than in the performer’s ability to produce a performance in which each and every note is metrically and pitch perfect. ‘Entasis’ can be seen as the balance between a feeling of predictability and one of uncertainty, and this is what gives music its sense of anticipation, delayed gratification, excitement and musical thought.

More Opinion

-

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'?

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'? -

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans -

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here -

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'