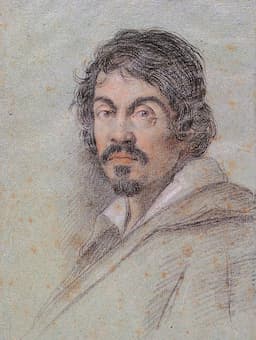

Portrait of Caravaggio by Ottavio Leoni

In 2021 we commemorate the Quincentenary of the birth of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610). He was an enigmatic, rebellious and dangerous individual, and he did affect a paradigm shift in the arts. His paintings probed the physical and emotional state of the human condition, and his dramatic use of lighting would become a dominant stylistic element.

Caravaggio: The Lute Player

Caravaggio painted the stories of the Bible as visceral and often bloody dramas. He staged the events of the distant sacred past as if they were taking place in the present day, often working from live models dressed in starkly modern dress. “Caravaggio had a noteworthy ability,” an art critic wrote, “to express in one scene of unsurpassed vividness the passing of a crucial moment.” These scenes often feature violent struggles, torture and death, with subjects transfixed in a blinding shaft of light. He preferred to paint “his subjects as the eye sees them, with all their natural flaws and defects instead of as idealized creations.” It is this intense realism and great sense of drama for which Caravaggio is now famous. Caravaggio’s effect on a new Baroque style directly influenced Rubens, Bernini, and Rembrandt. As was concisely formulated by an art historian, “what begins in the work of Caravaggio is, quite simply, modern painting.”

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina: Missa Tu es Petrus (King’s College Choir, Cambridge; Stephen Cleobury, cond.)

Caravaggio: The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew

Caravaggio hailed from Milan, but as we can tell from his name, grew up in the town of Caravaggio. He entered into an apprenticeship with the Lombard painter Simone Peterzano in 1584, and he might have visited Venice. In 1592, he was forced to leave Milan for Rome after having seriously wounded a police offer in a quarrel. Initially, Caravaggio worked in a factory-like workshop producing “painted flowers and fruit.” Leaving the workshop behind in 1594, Caravaggio was searching for ways to become an independent artist. He began to cultivate contacts with influential collectors and he attracted the patronage of Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte.

Caravaggio: The Calling of Saint Matthew

“For Del Monte and his wealthy art-loving circle Caravaggio executed a number of intimate chamber-pieces—The Musicians, The Lute Player, a tipsy Bacchus, an allegorical but realistic Boy Bitten by a Lizard, and other adolescent models.” His true reputation as an artist, however, would depend on public commissions, and he was contracted to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in 1599. The two works “Martyrdom of Saint Matthew” and “Calling of Saint Matthew” was an immediate sensation and the artist was hailed as a great visionary. “The painters then in Rome were greatly taken by this novelty, and the young ones particularly gathered around him, praised him as the unique imitator of nature, and looked on his work as miracles.”

Emilio Cavalieri: Representation of Soul and Body (excerpts) (Rosita Frisani, soprano; Alessandro Carmignani, tenor; Carlo Lepore, bass; Michel van Goethem, counter-tenor; Roberto Abbondanza, baritone; Giovanni Pentasuglia, tenor; Marcello Vargetto, bass; Patrizia Vaccari, soprano; Marinella Pennicchi, soprano; Alessandro Casari, counter-tenor; Gian Luigi Maria Ghiringhelli, counter-tenor; Gastone Sarti, bass; Prague Philharmonic Children’s Choir; San Petronio Cappella Musicale Orchestra; Sergio Vartolo, cond.)

Caravaggio: The Beheading of St John the Baptist

Empowered by his success, Caravaggio secured a string of prestigious commissions for religious works. His fame continually increased, but he seemed to have handled his success rather badly. A contemporary account informs us that “after a fortnight’s work he will swagger about for a month or two with a sword at his side and a servant following him, from one ball-court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or an argument, so that it is most awkward to get along with him.” A police report describes him as “a stocky young man with a thin beard, thick eyebrows and black eyes, who goes dressed all in black, in a rather disorderly fashion, wearing black hose that is a little bit threadbare, and who has a thick head of hair, long over his forehead.” On 29 May 1606, he killed a young man named Ranuccio Tomassoni in a formal duel on the “tennis court” (jeu de paume) of the French ambassador to Rome. While his patrons had generally been able to protect him, they could not cover for him this time. Caravaggio fled to Naples with a bounty on his head. Relying on family connections “the most famous painter in Rome became the most famous in Naples.” He immediately secured a stream of important church commissions, but fearful of being pursued, traveled to Malta.

Claudio Monteverdi: Vespers for the Feast of the Ascension (Irena Troupova-Wilke, soprano; Susanne Rydén, soprano; Detlef Bratschke, alto; Eric Mentzel, tenor; Hermann Oswald, tenor; Manuel Warwitz, tenor; Thomas Herberich, bass; Gunther Schmidt, bass; The Schutz Academy; Howard Arman, cond.)

Caravaggio: Judith Beheading Holofernes

Caravaggio began work on the largest of all his paintings, “The Beheading of St. John,” for the oratory of the conventual church, now co-cathedral, of Valletta in Malta. However, his stay in Malta was short-lived as he assaulted a senior knight of justice with a pistol. Caravaggio was thrown in jail, but with the aid of an accomplice managed to escape. He found refuge in Syracuse, Sicily, and created a number of haunting masterpieces.

Caravaggio: The Denial of Saint Peter

On the run from the man he had injured on Malta, Caravaggio returned to Naples in 1609. There he was attacked by four unknown assailants outside a Neapolitan tavern of ill repute and so severely wounded that he remained close to death for several months. While recovering from the attack he created his last two paintings, “The Denial of Peter” and “The Martyrdom of St. Ursula.” When he attempted to return to Rome, he was once more arrested and detained. He did manage to bribe his jailors and escape, but died on 18 or 19 June at the age of 38. His violent exploits and volatile character together with his presumed homosexual tendencies have greatly reawaked interest in Caravaggio ever since the mid-20th century. Caravaggio “was a violent man who lived in violent times, but he was a more subtle, sensitive, and intellectually ambitious artist than the myths that have accumulated around him might suggest.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Adriano Banchieri: Il zabaione musicale (Lino Toffolo, narrator; Prague Madrigalists; Damiano Binetti, cond.)

Excellent article. The music in the art of Caravaggio is abundantly clear and dramatic.