RIGOLETTO (1967) – at the end of the performance, L to R: Naval Havaldar, Cesar Coelho (Conductor), Imelda Lobo (Maddalena), Paolo Silveri (Rigoletto),

Celia Lobo (Gilda), David Parker (the Duke) and Derek Bond (Director)

“I always sang. Both my father (Edwin) and his sister, Muriel were gifted singers, but Edwin was streets ahead because he was also a brilliant pianist and, from my very youngest years, I had the pleasure and honour of listening to him play. His love for music was great and he and my mother (Emma) had a vast collection of records. So, all my life, almost from infancy, I was surrounded by music of the operatic and symphonic styles,” is Celia Lobo’s (née Baptista) clipped response in a vivace to the question when did she start singing? Music was her constant companion from childhood, whether as family entertainment or her healing.

THE GEISHA (1956) – Celia Lobo (Geisha)

Musical soirées were common at their home with Edwin, a tenor baritone, at the piano.

“He was a Fellow of Trinity College, London and encouraged me totally till I went to Gool Dotivala (voice trainer in Bombay of old). With Gool I learnt a lot from her over three or four years.”

That’s when Celia realised that to master her passion she would have to wend her way to the UK, the best known location for voice training in 1956, she believes.

THE GEISHA (1956) – Celia Lobo (Geisha)

Aspiring to study music, mother Emma made it clear that there was no music study unless Celia was a graduate. After passing her general BA, the 17 year-old, sashayed to the Guildhall School of Music, London from the Gothic corridors of Sophia College, Mumbai, her town of birth. She also recalls her older sister Shirley who would set off a song and four of the five siblings would harmonise in parts. All five children, three girls and two boys, of Edwin and Emma learnt music. Celia started with the piano and recounts the raps on her knuckles for errant playing. She found her voice soon and never looked back.

LA TRAVIATA (1962) – Celia Lobo (Violetta)

Just before she took to the sea, she was offered her first light opera of the Geisha Girl by Lionel Monckton in 1956 at Sophia College. Celia sang whenever she heard the piano in the basement in a sing-along with other hostelites of the college. At one such outpouring, her friend Pinky Dotivala told her to audition for the operetta. Before she knew it Celia was rehearsing for the lead role Mimosa San with barely a month at hand. That catapulted her to heady fame for a teenager.

The year 1952-’53 was annus mirabilis for Celia, barely 15 years old, Celia met her future husband Trevor. However, Trevor marched into the National Defence Academy in Poona with a view to join the army for his career. That accelerated the friendship to something more meaningful till Celia’s determination to go study voice training. This dramatically changed the romance to a rallentando in 1956. They decided to go their separate ways – and she sailed her way to the UK.

LA TRAVIATA (1962), ACT I

With a few cents in her pocket and determination worth a million, Celia set sail for London. It was the era when one voyaged by ship between India and England. Straight off the boat in London, she studied diligently for five years, two years of which were under Sumner Austin – the longest stint she had under one trainer at the Guildhall.

With financial help from aunts and friends, Celia was met in London by none other than her future brother-in-law, to be betrothed to Shirley! Life consisted of soup and operas – the parsimony of soup traded in for the extravagance of the opera! A few Maria Callas and Joan Sutherland concerts later, she ended in a job as a secretary – which she found was the best paid job that suited her keeping body, soul and the Guildhall together. The speed typist found herself at the Indian High Commission and ultimately as Secretary to the Managing Director of Blackwood Hodge.

LA TRAVIATA (1962), ACT II – Celia Lobo (Violetta) with Conal Almeida

(the elder Germont)

It was already time to return to India, to a Bombay, Celia found much changed. Though five years had sailed past, meeting Trevor again seemed like only yesterday. But in your early twenties, being in a duet with your love, makes the world a wonderful place.

Recently returned, Bombay saw her sharing a recital with violinist Adrian D’Mello, Theresa Halloween accompanying both the soloists in 1960. Celia recounts one of her may-the-earth-swallow-me moments when she forgot to acknowledge her pianist, Theresa – a well celebrated accompanist those decades! A lesson well learnt, never to be repeated.

Lucia di Lammermoor (1964), ACT I – Celia Lobo (Lucia)

and Conal Almeida (Enrico)

The music scene in Bombay had picked up considerably by the time of her homecoming; The Bombay Madrigal Singers’ Organisation (BMSO) had been formed to produce operas with local talent. Being a fresh artist who returned from training in the UK, made her a clear choice for the newly upcoming opera of Giuseppe Verdi’s Il Trovatore. The Organisation offered her the mezzo soprano role of the old Gypsy Azucena. Despite straining her natural high soprano range, she accepted it. She managed the lower notes but regrets taking it on as she believes that the dark tone the character of the gypsy must have, eluded her natural range. Some of these blunders can never be lived down but continue to elicit a smile decades later.

Trevor and Celia were married in 1962 and the young couple was initially based in Delhi when she was offered the role of Violetta in “La Traviata” by Verdi in Bombay. “I was delighted with the offer and agreed on condition that I be paid a fee, per performance, plus all expenses” a stance unheard of those days. Derek Bond a theatre person with great knowledge of opera was appointed the Director. Once the music score and recording reached her in Delhi from Bombay, it took her three weeks to learn the part before she would fly intercity for rehearsals.

Lucia di Lammermoor (1964), ACT I

This was also the year China and India were at war and Trevor was summoned to a small town with accommodation in the troop’s barracks which were unused since the Second World War! They were given five lodgings in a row. He upped and resettled in the town of Shahjahanpur in the state of Uttar Pradesh. To add to the excitement, water was hosed into the house from a tap located outside at the rear of the barracks. In keeping with the high for opera, Celia flew back to this little town the day after the last performance in Bombay, the music capital of India.

The following year BMSO put up Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. Unfortunately Celia was unable to participate in all the performances as she was expecting their first child Deirdre who was born in January, whilst Celia rehearsed for performance that December. She says,

“That I had to work my tail off for this role is putting it very mildly. Lucia is a notoriously difficult role (for the soprano) with a great deal of coloratura work and many, many ‘showpiece’ arias, crowned by the famous “Mad Scene” which lasts for 27 minutes of solo singing of the most devilishly difficult kind. It’s a real ‘tour de force’ and it came off like that.”

The tenor lead of Edgardo was played by Luigi Infantino of Milan’s La Scala. Celia soon understood that he wanted to be showcased better than an Indian singer, given his pedigree, despite the opera being the soprano’s. Celia recounts,

RIGOLETTO (1967) – Celia Lobo (Gilda)

“…on opening night, in the first act love duet when Infantino and I had to end the beautiful love duet together, holding that last note for a given number of beats, he held on and on and on, whilst I had already cut out. The next night I got my own back and latched on to his voice, holding on till HIS breath ran out.”

He also demanded thigh-high leather boots two days before opening night, putting the costume ladies and the whole team into a tizzy, paying no heed to the fact that all assistance was amateur, voluntary and only passion drove them.

In 1965, BMSO produced Norma by Vincenzo Bellini. Celia had given birth to their second child Carolyn in October and sang the breathy Bellini in all his glory in December that same year. She sang ‘Casta Diva’ with reasonable execution, three months after giving birth. However, she advices singers never to attempt something similar as “I literally felt as if I had no diaphragm and my mid-section was woefully wanting in muscle control.”

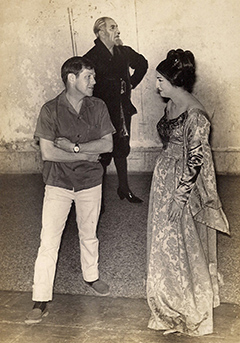

RIGOLETTO (1967) – Celia Lobo (Gilda) with Derek Bond (Director) backstage

The year 1966 saw her third child Ashley being born and so she was out of the opera Faust by Charles Gounod as even she could not manage two children and a third on its way. So Celia was not Marguerite that year but having delivered Ashley in March, she readied for Gilda in Verdi’s Rigoletto! Rehearsals were a cakewalk compared to the performances at the time of the infamous Koyna earthquake. Celia returned home after a week of not seeing her children as the rehearsal schedule forced her to banish that thought. Few days of her return, the earthquake struck and the family spent the night in the outdoors. Since power was not restored before the staging of the opera, the flounced lead singers had streams of perspiration running down their legs, as gravity took its own course. The theatre too had no air conditioning and the audience was given hand-held fans, leaving them to decipher whether the streams down the cheeks of the performers were sweat or tears.

RIGOLETTO (1967), Curtain Call – (L to R) Paolo Silveri (Rigoletto), Cesar Coelho (Conductor),

Celia Lobo (Gilda) and David Parker (the Duke)

Paolo Silveri (Rigoletto) was imported from Italy, and as the evening progressed he cautioned Celia that he was about to faint with the heat. Fearing his six feet frame may collapse on her, Celia led him to a chair to make his dramatic pass-out. Director Derek flew in a rage at curtain and sought an explanation from them as to why they changed the action and calmed down only when Celia told him why she thought on her feet rather than experience a personalized earthquake of their own on stage.

TOSCA (1968) – Celia Lobo (Tosca)

With so many operas already staged, could Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca be far behind? In 1968 this grand opera was staged. By now Zarine Billimoria and Roshan Havaldar were adept at costume design and execution. “Zarine Billimoria did a splendid job of designing gowns meant to minimizing my shortcomings and maximizing my strengths,” Celia recalls. Unfortunately, no pomp and sartorial cover could masquerade her fear of jumping off the battlements as Tosca commits suicide at the end of the Opera. With her back to the audience, the heroine had eyes tightly shut and took a leap of faith in the waiting arms of Ratan Tata, the stage manager.

Celia had her share of personalised drama in the same Opera. Two choristers were overheard plotting to stop Celia from jumping off the stage onto the mattresses awaiting her fall. As she sang her last lines declaring to meet the villain Scarpia before God, the two plotters made a dash for her. However, being prepared, Celia made an even more dramatic exit. This did not stop Derek from raving “Who was that bloody idiot that made a dive for Celia’s legs?”

TOSCA (1968), ACT I – Celia Lobo (Tosca) with Otello Borganovo (Scarpia)

Otello Borgonova, also an Italian bass was in the role of Scarpia (the villain) in the same opera. Having to fall down at the end of the performance, he shot out a torrent of incomprehensible Italian that Celia had not given him enough room to drop. The fact was that his trousers had split at a vulnerable seam and there were a few seconds to curtain call. Celia and Ratan held the curtain for him as he bowed and literally bowed out into the wings. As the pants had seen better days, the second day was a repeat performance of this rupture. This time Celia dramatically loaned him her cloak, he draped her cloak over his arm and covered himself appropriately and took the bow!

Those years sponsorship was not the major way for minor things like opera. BMSO ran out of funds and were unable to do full scale productions and did two operettas but with piano accompaniment. Needless to say, the audience also found these disenchanting.

TOSCA (1968), ACT II – Celia Lobo (Tosca) with Otello Borganovo (Scarpia)

Almost a decade later, Celia went back to the Guildhall to do a refresher course under Walther Gruner, who was transiting Bombay. So Celia waved good bye to her city and was back in London the summer of 1978. She found herself auditioning for a German company who wanted copies of her brochure and her headshot to cast her for future performances. However, circumstances made up her mind for her. Trevor was hospitalized with acute sciatica. That was the double bar at the end of the page of her performing career.

On her return, the opera performer went back to stenography and held jobs in two corporations for practically two decades with intermittent performances and productions of musical and other light operas. She also conceived and wrote a musical on Broadway hits termed Best of Broadway and incorporated Cats, I love Paris, Surprise form Chorus Line and Hookers on Broadway – the story of an old hooker and a young one. Cabaret, Man of La Mancha, were also represented with different songs. Practices were at home which meant the house was the teaching room for 12 soloists who came in and out for training, perfecting, polishing and everything that goes into a finished performance.

TOSCA (1968), ACT II – (L to R) Otello Borganovo (Scarpia), Rowland Jones (Cavaradossi)

and Celia Lobo (Tosca)

Celia’s artistic passion has given two of her three children their profession. Deirdre is a professional singer in San Francisco. Among the several hats she wears she has founded the Celia Lobo Academy of Voice to carry on her mother’s legacy. Carolyn pours her energies in building communities and neighbourhoods in Brisbane, Australia and gives talks to make communities aware. Ashley, the youngest, is a choreographer, dancer and founder of a dance school in India called Danceworx Performing Arts Academy. He is also a founder director of Navdhara India Dance Theatre, located at Bombay. Trained in Australia, Ashley decided to return home and enthuse the underprivileged to step out with their creative compulsions.

Celia scales life between three continents, in two hemispheres and three homes. That is her current stage on which she continues to perform. No curtains for this diva.

Celia Lobo and Tehmie Gazdar – NCPA Recital

All images have been sourced from the private collection of Celia Lobo.

By Mehroo Kotval

This Article first appeared on Serenade Magazine on August 21st, 2019.

Celia Lobo passed away in Bombay on June 17, 2024, at the age of 88. Her funeral is set for Sat., June 22, 4.00 pm local time. The funeral will be live streamed. On the East Coast of the US this makes it the following morning, Sun. June 23 at 6.30 am.