Musicians through the ages have had a keen sense of responsibility to the music of composers of their time. We are fortunate there were cellists who inspired composers to write new works for the instrument, (Rostropovich inspired both Prokofiev and Shostakovich); cellists who directly commissioned works, (in the case of Walton’s Cello Concerto: Gregor Piatigorsky) and cellists who advocated, sometimes strenuously, for new music for the cello (in the case of the Dvořák’s Cello Concerto: Hanuš Wilhan). It is no less important to champion the music written today. Many prominent composers are composing cello concertos and every cellist ought to include some of these works in their repertoire. I’d like to draw your attention to excellent works of six composers, which you may not know about.

Pēteris Vasks

Vasks: Cello Concerto No. 1 (David Geringas)

Vasks’ Concerto No. 2 Presence for cello and string orchestra, came to be due to the tenacity of cellist Sol Gabetta. When she was eighteen, she heard and fell in love with Vasks’ solo cello piece Grāmata čellam. Once she established a prominent career, Gabetta pursued Vasks until he agreed to write a piece for her. The composer explains the title Presence, “by which I mean that I am here. I am not distant. With every breath, I am here in this world, with all my ideals and dreams of a better world… [the work] is dominated by a mood that suggests the soul ascending into the cosmos. I was then inspired to conjure up the idea of the soul returning to earth and starting a new life…in the form of a lullaby.”

Sol Gabetta © Uwe Arens

Vasks: Presence Cello Concerto No. 2 (Sol Gabetta)

Errollyn Wallen, born in Belize in 1958, based in the UK, is considered “the Renaissance woman of contemporary British music”. Yet she has defied categorization. She is a singer-songwriter, a pianist, a composer of opera and stage works including ballet, a composer of chamber music, song cycles with dance and film, jazz, piano solos, choral music, a hit children’s opera, and an award-winning percussion concerto for Colin Curry. Her output is astonishing.

Errollyn Wallen © Martin Godwin for the Guardian

Wallen’s Cello Concerto was commissioned by The Orchestra of the Swan, and premiered in 2008 by cellist Matthew Sharp. It is also for cello and strings, and relatively short at twenty-two minutes, but don’t let that fool you. It is brilliant, full of jazz touches, intricate dance rhythms, and in improvisatory feel. This work also opens with a passionate and free-style cadenza of over four minutes. Much of the concerto is cantabile, (smooth and singing), and traverses the entire range of the cello. There are two short cadenzas, the first is technically complex, the second towards the end of the piece, intense and anguished. Wallen sums up in tragedy with a heart-rending melody accompanied by soft tremolo strings in the background, ending as if interrupted, with a trill, and leaving us with a question mark. Her music is free-spirited, gutsy, and enthralling.

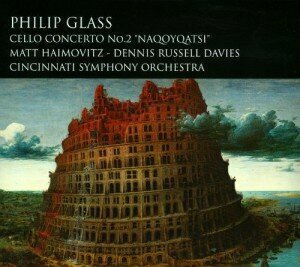

Philip Glass

Philip Glass: Cello Concerto No. 1 (Julian Lloyd Weber with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Gerard Schwarz)

Following the tradition of composers like Korngold and Rosza who wrote for movies and then adapted the music for solo cello, Philip Glass rewrote his score to the 2002 film Naqoyqatsi: Life as War, originally performed by Yo Yo Ma.

Glass: Cello Concerto No. 2

New World

Intensive Time

The Vivid Unknown

The new version was commissioned by the Cincinnati Symphony while Glass held the title of Creative Director with the orchestra. Cello Concerto No. 2 draws from the score of the film but is reduced from the eleven movements to seven. The work begins like Mars from Holst’s The Planets—a low robotic voice, in an irregular rhythm. When the cello enters with an undulating and beautifully written theme, we feel the power and passion conveying melancholy, remorse, and regret. The fourth part begins with pristine harmonics in the cello accompanied simply by soft percussion, like thunder in the distance. Movement seven also begins with a tender cello cadenza, some of it suggestive of solo Bach. This work, although it has all of Glass’ fingerprints—the minimalist ostinato configurations, prodding brass, and flowing melodic motifs, comes across as a romantic cello concerto would. Cellist Matt Haimovitz performed the premiere in 2012, with Dennis Russell Davies conducting the Cincinnati Symphony. Since then Haimovitz has recorded the concerto and it has received several performances from other cellists.

The next part of the series continues with six composers whose cello concertos we ought to listen to and perform.