Rebecca Clarke

We have not exhausted the gorgeous cello music written by women composers by any means. Here are three more outstanding gems.

Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) is another composer who deserves the limelight. A world-class viola soloist, chamber musician, and composer, Clarke not only had to deal with Victorian prohibitions but also her controlling and abusive father. Clarke began music lessons at the age of nine on the violin. She was allowed to enroll at the Royal Academy of Music during her teenage years, that is, until one of her professors proposed marriage when she was only 19. Clarke’s father immediately withdrew Rebecca from the university and enrolled her at the Royal College of Music instead. But she was unable to complete her studies. In 1910 Clarke’s father abruptly barred her from home and cut her off financially. Somehow, she was able to support herself as a performer—one of the first female orchestral players in London. She toured extensively and internationally as a viola soloist and as a chamber musician eventually settling in America before World War II. Earlier in the century, in 1919, renowned American patron of the arts Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge held the Berkshire Chamber Music Prize competition and Clarke’s viola Sonata tied for first place with a work by Ernest Bloch. Coolidge awarded the first prize to Bloch. It was thought perhaps Clarke’s sonata was written by Bloch under a pseudonym. How could a woman write such poignant music? After her marriage in 1944 Clarke ceased writing music and increasingly battled depression. Only twenty of her works were published during her lifetime, many of them remaining unpublished until recently.

The heart-rending Rhapsody for Cello is a masterful work. It’s inexplicable that the piece went unpublished for almost a century after it was commissioned by Coolidge for her 1923 Berkshire Festival. The piece was premiered there by the great British musicians cellist May Mukle, Clarke’s best friend and collaborator, and Myra Hess on piano.

The Rhapsody begins molto lento (very slow) with a captivating melancholy line, to me reminiscent of Bloch’s music. In fact, the Adagio e molto calmato second movement begins very low in the cello range and incorporates harmonies and intervals very like Bloch but as it progresses, more impressionistic effects are introduced including veiled melodies and nebulous rhythms fading away with otherworldly pizzicatos. In contrast, the third movement is vehement and ardent, which moves directly to the unrestrained opening of the Lento finale, but soon it returns to the affecting mood of the opening. What a captivating, powerful, and important cello work!

Rebecca Clarke: Rhapsody (Raphael Wallfisch, cello; John York, piano)

Raphael Wallfisch the brilliant cellist, recorded several of Clarke’s works for cello in 2016 including her Sonata for Violoncello and Piano—a reworking by Clarke of her viola sonata. The Impetuoso first movement begins with a dramatic cello cadenza—romantic and powerful. A contrasting, dreamy middle section is in the richest range of the cello and evokes repose. The passion of the opening returns with thrilling turns in the piano. The second movement vivace and almost scherzo-like is impressionistic in style with a bevy of effects—muted sections, pizzicato, harmonics. A wistful and tender slow movement follows connecting or attacca to the breathless last movement.

Rebecca Clarke: Cello Sonata – I. Impetuoso (Raphael Wallfisch, cello; John York, piano)

Clarke’s oeuvre includes several songs and choral works as well as chamber music and today there is abundant and much-deserved interest in her compositions.

Rita Strohl © lepetitrenaudon.blogspot.com

Rita Strohl (1865-1941) the pseudonym for Aimée Marie Marguerite Mercédès Larousse La Villette, was a French composer and pianist. By the age of 13 she was studying piano at the Paris Conservatoire and receiving private lessons in singing and composition. Her compositions include songs, music for orchestra, chamber music, a mass, works for orchestra and organ, and large-scale productions including operas. Acclaimed by illustrious composers of the time including Saint-Saëns, Vincent d’Indy, and Gabriel Fauré, her music is lyrical, and expansive. Strohl’s Great Dramatic Sonata in four movements was premiered in 1892, and it’s impressive. The music tells the story of Titus and Bérénice, based on quotations from Racine’s tragedy Bérénice (1670).

Throughout, the piano and cello are on equal footing. The beginning is mysterious, hesitant, and free in rhythm. When a captivating melody enters, the enigmatic elements linger and the movement continues powerfully almost symphonic in its breadth, covering the entire range of the cello with scintillating soprano melodies and deep baritone phrases. The movement ends delicately muted. The second movement, a vivace is quite delightful sounding and reminiscent of the Mendelssohn Scherzo, and with a gorgeous lyrical second theme. This is so enjoyable to play. The Lento Tristamente (slow and sadly) opens with the piano solo and beautifully sets the tone when the cello enters soulfully and with heartbreak. Such poignant writing! The finale, an Allegro molto movimento, full of dramatic sweeping lines and rhythmic vitality, is breathtaking and virtuosic. Acclaimed cellist Gary Hoffman recently performed Strohl’s sonata for the 4th Palazzetto Bru Zane Festival in Paris from the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, and the program was broadcast on Medici.tv. If you enjoy the music of César Franck you will love this piece.

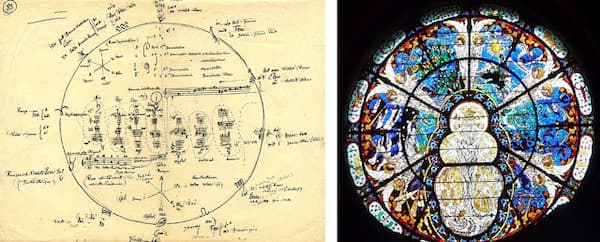

A “cosmic” score by Rita and a stained glass window produced by her husband © lepetitrenaudon.blogspot.com

Strohl’s vision and talent is astonishing now that we look back. Bristling with ideas, she attempted to found a festival entitled La Grange similar to the Bayreuth festival in Germany that primarily features the operas of Richard Wagner. She hoped to showcase her massive works—including grandiose operas with elaborate scenes and complicated equipment, one with a five-day Celtic cycle. But the First World War interceded. Afterwards, extremely disappointed and traumatized, she composed less and less and her dreams crumbled.

I hope very soon more performers and audiences will discover Strohl’s music. Many of her works are yet unrecorded, unedited, and in manuscript form.

Our series of articles featuring the outstanding cello music of women composers continues in part IV. I hope you’ll join me on this journey.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Rita Strohl: Titus et Bérénice (Edgar Moreau, cello; David Kadouch, piano)

I am a great-nephew of Rebecca Clarke’s and the owner of her rights as composer and author. Three things cry out for correction in your post. First, Clarke’s triumph at the 1919 Coolidge Competition was an international sensation, instantly making her a celebrity in her own right, in her own name. The worldwide newspaper coverage overwhelmed any speculative gossip about the Sonata’s authorship—indeed, much was made of the fact that several of the judges thought the piece was by Ravel until the moment the envelope was opened. Second, it is entirely explicable that Clarke’s Rhapsody went unpublished for so long: she was never satisfied with the piece, and did not offer it for publication—in fact, she gave the manuscript to Mrs. Coolidge and did not keep a copy for herself. The published edition (Nimbus Music Publishing, 2020), more than five years in the making, was the result of the first expression of interest actually received. Clarke’s other works for or with cello were published either by Clarke herself, or posthumously by Oxford University Press (2002, 2003). Finally, Clarke had her ups and downs, like anyone else, but she was charming, funny, kind, and as a professional almost hyperactive—possibly the least depressed person you might ever expect to meet; Clarke’s so-called “struggles with depression” were invented by latter-day musicologists, in order to shoehorn her into their own ideology. For accurate, up-to-date information on Clarke’s life, career, and works, please see her official website, http://www.rebeccaclarkecomposer.com. For further details, and for the only legitimate access to Clarke’s unpublished manuscripts and papers, use the “Contact” page on the website. (Christopher Johnson, Brooklyn, New York, USA)

Hello Christopher and thanks for the great information. Many women were often “shoehorned” and this prevented extremely gifted musicians, writers, and scientists from accomplishing what they might have. And like any great artist, the information that she was never content with her work is our artists’ fate but how else would one continue to improve and excel without constant probing, revising, exploring? Thanks for writing and we are pleased to know Ms. Clarke is at last getting the recognition she is due.

Best

Janet

Hello – My colleague and I would love to perform the Sonata Dramatique for cello and piano ‘Titus et Bérénice’ by Rita Strohl. Your site has wonderful information on this work – can you possibly let us know from where we might be able to purchase the music score? Thankyou!

Hello Brieley,

Thanks for writing. You should be able to ask the world catalogue at the link below to have a copy sent to your local library. I don’t think it’s readily available in music stores. I hope this works.

All best

janet

http://www.worldcat.org/title/titus-et-brnice/oclc/1022941676&referer=brief_results

I am a cellist and would love to perform Sonata Dramatique for cello and piano ‘Titus et Bérénice’ by Rita Strohl. can’t seem to find the score anywhere. could you please tell me how/where I can get the score? would appreciate it.