Princess Cristina Trivulzio Belgiojoso

Vincenzo Bellini: I Puritani, “Suoni la tromba”

Vincenzo Bellini: I Puritani, “Suoni la tromba” Vincenzo Bellini had come from humble beginnings in Catania to take the operatic stages in Italy, London and Paris by storm. His last opera I Puritani (The Puritans) was first staged in Paris in January 1835, and is based on a deeply obscure French play called “Roundheads and Cavaliers.” It turns on a remarkable change of heart by the English Puritan governor general, Lord Gualtiero Walton. Having promised the hand of his daughter, Elvira, to the stalwart Roundhead colonel Sir Riccardo Forth, he is persuaded by his brother Giorgio to allow her to marry the man with whom she has fallen in love, Lord Arturo Talbot, a Cavalier and Roman Catholic partisan of the deposed Stuart monarchy. Bellini wrote to his friend Francesco Florimo after the premiere, “The French have all gone mad; there were such noise and such shouts that they themselves were astonished at being so carried away … In a word, my dear Florimo, it was an unheard of thing, and since Saturday, Paris has spoken of it in amazement.” And the “revolutionary Princess Belgiojoso” took full advantage of Bellini’s fame and her stable of exceptional pianists and commissioned the Hexameron. Franz Liszt was in charge of assembling this set of variations on the march theme by consulting some of his pianist friends. And Liszt got the ball rolling with a substantial introduction and the transcribed theme.

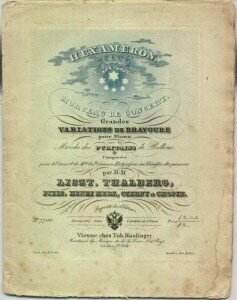

Hexameron: Grandes variations de bravoure sur le marche des Puritains, “Introduction, Tema” (Liszt)

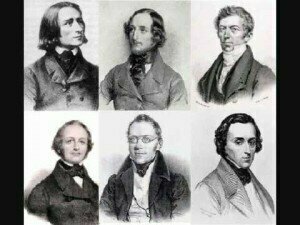

Liszt allocated the 1st Variation to his supposed rival Sigismond Thalberg, who characteristically placed the theme in the middle voice. Supported by right-hand flourishes and deep bass patterns, the music gives the impression of needing a three-handed pianist to be realized. A somber Liszt variation proceeds to a bravura version by Johann Peter Pixis, to which Liszt adds a transitional Ritornello.

Liszt allocated the 1st Variation to his supposed rival Sigismond Thalberg, who characteristically placed the theme in the middle voice. Supported by right-hand flourishes and deep bass patterns, the music gives the impression of needing a three-handed pianist to be realized. A somber Liszt variation proceeds to a bravura version by Johann Peter Pixis, to which Liszt adds a transitional Ritornello. Variation 1 (Thalberg)

Variation 2 (Liszt)

Variation 3 (Pixis), Ritornello (Liszt)

Henri Herz furnished variation 4, and Carl Czerny provided variation 5. In fact, Czerny had moved from Vienna to Paris just in time to take part in the Hexameron project. Liszt had written, “My dear and beloved Master, if you ever entertain this idea (moving to the piano-playing capital of Europe), I will do for you what I would do for my own father.” Liszt followed the Czerny variation with an interlude marked “Fuocoso molto energico,” and a tender recitative.

Variation 4 (Herz)

Variation 5 (Czerny), Fuocoso; Quasi recitative (Liszt)

The Hexameron was not finished in time for the intended performance after the Thalberg/Liszt duel, and it probably was Chopin’s fault. The princess writes to Liszt two full months after the deadline. “Here, my dear Liszt, are the variations of M. Herz and the others, which you already know. No news from M. Chopin, and since I am still proud enough to fear making a nuisance of myself, I do not dare ask him. You do not run the same risk with him as I, which prompts me to ask if you would find out what is happening to his adagio, which is not moving quickly at all.” In the end, Chopin did submit variation 6, which Liszt links to his own spirited Finale. Haslinger of Vienna published the Hexameron in 1839 with a dedication to the princess. And we know that Liszt played the work all over Europe as an encore piece, and that he even made a set of orchestral parts so that he could play the work with orchestra.

Variation 6 (Chopin)

Finale (Liszt)