Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, 1829

Musicologists have suggested that “the life of Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1805-1847) is compelling proof that women’s failure to compete with men on the compositional playing-field has been the result of social prejudice and patriarchal mores, which in the nineteenth century granted only men the right to make the decisions in bourgeois households.” To be sure, Fanny’s father Abraham Mendelsohn did not actively support her compositional activities. As he wrote in 1820, “Music will perhaps become Felix’s profession, while for Fanny it can and must be only an ornament.”

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, 1842

Fanny was four years older than Felix, and both were musically precocious. Her virtuosity on the piano equaled, if not surpassed, that of her brother. Goethe paid her the ultimate compliment for a woman at that time when he wrote, “she plays like a man.” Both siblings started composing at an early stage, and although her brother was supportive he wrote, “From my knowledge of Fanny I should say that she has neither inclination nor vocation for authorship. She is too much all that a woman ought to be for this. She regulates her house, and neither thinks of the public nor of the musical world, nor even of music at all, until her first duties are fulfilled.”

The music room of Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel

According to scholars, “Fanny Mendelssohn struggled her entire life with the conflicting impulses of authorship versus the social expectations for her high-class status… her hesitation was variously a result of her dutiful attitude towards her father, her intense relationship with her brother, and her awareness of contemporary social thought on women in the public sphere.” When Fanny fell in love and married the court painter Wilhelm Hensel in 1829, she eventually settled into a prescribed domestic role. In all, Fanny wrote well over four hundred pieces, with only some of her compositions published and many more unavailable or destroyed. According to a contemporary critic, “The expressiveness of her compositions was unmatched.” Her last major work, the Piano Trio in D minor dates from 1847 and overflows with great energy and passion. It is a masterwork in the chamber music genre.

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel: Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 11 (London Bridge Trio)

Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen

The Italian composer, violinist and singer Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen (1745-1818) did not come from a musical family, but attained musical fame entirely through her own efforts. She became an outstanding violinist and was hired by the Ospedale dei Mendicanti in Venice as a musician. After studying violin and composition with Tartini in Padua, and spending 13 years at the Ospedale, Maddalena married the violinist and composer Lodovico Sirmen. The couple embarked on a highly successful European tour, performing several times at the Concert Spirituel in Paris. In London, she was advertised as “the celebrated Mrs Lombardini Sirmen,” and she performed to great acclaim in the Bach-Abel concert series. She also expanded her repertoire and became a singer. We know that she appeared as a vocalist in London, Paris, Dresden, St Petersburg, and various cities in Italy.

Her compositions were widely known, and after hearing a performance of her violin concerto, Leopold Mozart excitedly wrote, “After the symphony Count Czernin played a beautifully written concerto by Sirmen.” Publishers were eager to print her compositions, with most of them focused around the violin. Her string quartets are primarily in two movements, and “are notable for their interesting inner parts.” Written during a transitional period from the baroque to the early classical, these works feature beautiful melodic and modulatory ideas, “full of charm and feeling for sound as well as an early classical inflection.” Set in a clear structural form, Lombardini is constantly looking for an equal dialogue between the four voices. She composed her string quartets at the tender age of 24, but no compositions survive from the last three or four decades of her life because she had set new priorities as a singer. As such we are unable to trace her development from a highly talented violinist and composer to a mature artist.

Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen: String Quartet No. 5 in F Minor (Musica Fiorita)

Mélanie Bonis

Mélanie Hélène Bonis (1858-1937) was born into a Parisian lower-middle-class family and initially discouraged from pursuing music. Undeterred, she taught herself how to play the piano, and only at the urging of a family friend, and with help from César Franck, she was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire. Among her fellow students we find Gabriel Pierné, Claude Debussy, and the charismatic Amédée Hettich. She fell in love with Hettich, but her parents disapproved and married her to the industrialist Albert Domange. He was a widower, father of five children, hated music, and was 22 years her senior. Bonis raised her stepchildren and had three children of her own. When Hettich entered her life again in the early 1890s she devoted all her energies to composition. She became a highly esteemed composer, and when Saint-Saens first heard her piano quartet, he exclaimed, “I would never have believed that a woman could be capable of writing something of this kind. She knows all the tricks of our trade.”

Mélanie Bonis, 1908

Bonis composed roughly 300 works, including 60 piano compositions, numerous songs, large polyphonic religious works, 30 organ and 11 orchestral pieces, and around 20 chamber music compositions. Stylistically her works are cast in a post-Romantic tradition, and “range from light pieces to mystic songs, from pieces for children to works for the concert hall.” She explored the various possibilities of harmony and rhythm, and her later work opens increasingly in the direction of Impressionism. To conceal her gender during a time when compositions by women were not taken seriously, she shortened her first name to “Mel.” A good many of her late compositions have still not been published, and as she wrote to her daughter, “My great sorrow is that I never get to hear my music.” It’s time to change that, don’t you think?

Mélanie Bonis: Piano Quartet

Julia Frances Smith

Pianist, conductor, composer and musicologist Julia Frances Smith (1905-1989) hailed from Texas. To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the State of Texas, Smith composed her first opera “Cynthia Parker.” Based on a Texan subject, the plot tells the story of Cynthia Parker, who is kidnapped by Native Americans. Raised by the Comanche tribe, she eventually marries a chief and raises three children. At some point she is found by Texas Rangers, and returned to white society. However, unable to adjust and deeply unhappy, she takes her own life. Smith went on to write five more operas, including “Daisy,” based on the life of Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts in the USA. Her compositional portfolio also includes a symphony, two orchestral suites, a wind overture, a piano concerto, chamber music works, piano pieces, choral works and songs. Smith was highly active in helping to promote the cause of women composers in the US and organized concerts of works composed by her colleagues.

Cynthia Parker

Smith was a sharp critic of the state of contemporary music in concert halls and opera houses. In a 1987 interview she saw music torn between the extremes of profound simplicity in the music of Glass and extreme complexity in the twelve-tone system practiced by Babbitt and Wuorinen.

Cornwall, New York

“If only the Americans would just have a little confidence in themselves,” she explained. “It’s all right to have observed what these people have done, but why copy every new trend that comes along? What is that? Don’t they have anything of their own to say?” Smith infuses her compositions with elements of jazz, folk, and 20th century French harmonies. As a critic wrote, “her compositional style has an appealing directness and is mostly tonal, and the use of dissonances provided color in a highly original way.” The “Cornwall Trio” dates from 1966 and does not refer to the county in southwest England; instead it references Cornwall on the Hudson River in the State of New York where the composer first heard the birdsong that she used as thematic material.

Julia Smith: Cornwall (Thomas Albertus Irnberger, violin; David Geringas, cello; Barbara Moser, piano)

Germaine Tailleferre, 1894

It is said that Germaine Taillefesse (1892-1983) changed her name to “Tailleferre” to spite her father who refused to support her music studies. He considered music an unworthy pursuit, and a “woman studying music” he once remarked, “was no better than her becoming a streetwalker.” She never forgave him for his inflexible attitude towards her artistic gifts. Embittered, “she is said to have regarded his demise in 1916 as something of a relief.” Studying at the Paris Conservatoire she immediately won various prizes and caught the eyes of her fellow students Darius Milhaud, Georges Auric and Arthur Honegger. When she published her first string quartet in 1918, she was welcomed as a major talent into the private musical club that eventually blossomed into “Les Six.”

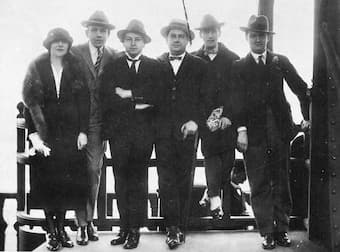

Les Six

Interestingly, she once remarked that Picasso gave her the “best lesson in composition” she ever received as he told her to “constantly renew yourself; avoid using the recipes that you have already found.” Tailleferre is considered the “most important French woman composer of all time.” She was an enormously productive composer, writing music until just a few weeks before her death at the age of 91.

Germaine Tailleferre, 1937

Tailleferre always had her finger on the pulse of her time and she composed in virtually every musical genre, ranging from opera and ballet to piano concertos, from symphonic works, solo piano pieces, music for small ensembles to well over 40 movie soundtracks. She left behind an extensive body of works representing almost 70 years of compositional engagement and over time forged a distinctive musical voice that valued clarity, spontaneity and charm. Her most famous compositions were written as early as the 1920’s and include her first Violin Sonata. Fresh, spontaneous and extremely effective, its four movements unravel lightly and elegantly. Imbued with ever-changing and unconventional harmonies each movement is strictly tied to different harmonic and rhythmic situations.

Germaine Tailleferre: Violin Sonata No. 1 (Malin Broman, violin; Simon Crawford-Philips, piano)

Please join us next time for more chamber music composed by women, including works by Cécile Chaminade, Rebecca Clarke, Grażyna Bacewicz, Jennifer Higdon, and Pauline Garcia-Viardot.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter