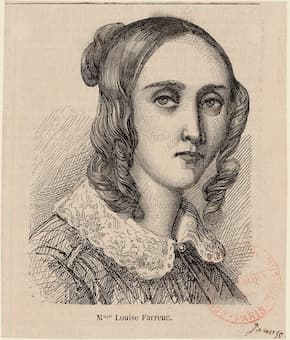

Louise Farrenc

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) was one of the first successful female composers in 19th century France. That opinion is not only based on 21st century assessments, but also on views expressed by her contemporaries. Robert Schumann wrote for example, “her works are so sure in outline, so logical in development that one must fall under their charm, especially since a subtle aroma of romanticism hovers over them.” The musicologist François-Joseph Fétis wrote in 1862, “Farrenc’s mind has conceptual strength of a consummate master,” and in the supplement to his Biographie universelle, Adolphe Julien wrote just three years after her death, “as a woman she has left us, but the teacher lives on in her pupils and the composer in her works.” Farrenc’s musical inheritance did not originate with her French compatriots but came from Vienna. More specifically, in her instrumental chamber works Farrenc primarily turns to Ludwig van Beethoven as a compositional model. After the premiere of her first piano trio, a critic placed Farrenc “in the first rank among composers of chamber music, as she is among the first who have sought to reconcile purity and solidity of style with the resources of the modern piano; she has studied the great works of the old masters, and has restored their true meaning.”

Louise Farrenc, 1855

Farrenc’s Sextet in C minor exhibits great imagination and inventiveness. Composed in 1852 it is the first work in history that uses the combination of the piano and wind quintet. In composing the Sextet, Farrenc did follow the models of the quintets of Mozart and Beethoven, “which were well known in Parisian music circles.” Interestingly, Farrenc added the flute to the instrumentation in possible reference to her mentor Antoine Reicha, who famously had published 24 wind quintets some decades earlier. The wind quintet functions as an orchestral ensemble, “supported by a delicate and sparkling piano part.” Farrenc was an exceptional pianist, and her piano parts were greatly admired “for a simplicity of style and delicacy of touch.”

Louise Farrenc: Sextet in C minor, Op. 40 (Stuttgart Wind Quintet; Gitti Pirner, piano)

Amy Beach

When Amy Beach (1867-1944) celebrated her 75th birthday, a critic wrote “she has always been a romantic in the best sense of the word—a devotee of beauty and a follower of the gleam. She has not been tempted into impressionism or atonality, nor has she strayed into the jungle of discords. Her music has a timelessness that should make it enduring.” To be sure, Beach was profoundly influenced by the Germany Romantic tradition, and she enhanced her rudimentary composition lessons by tirelessly studying the musical scores of Bach and Brahms. One of her most popular works, the Quintet for Piano and Strings in F-sharp minor had its origins in her public performance of Brahms’s Quintet Op. 34. The Brahmsian influence is unmistakable in sound and style, and also in form and harmonic language. However, in her final piano chamber work, the Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 150, Beach looks beyond Brahms and fashions a work original in style and composition. The trio “showcases Beach’s evolution as a composer and represents the peak of her creativity during her late years.”

Amy Beach

Beach started work on the piano trio in 1938, and she notes in her diary, “Trying a trio from old material. Great fun.” In an attempt to sum up her compositional career, Beach drew together sketches and ideas from earlier works. In fact, the “old material” refers to an arts song, a piano piece, and two folk songs. It only took her fifteen days at the MacDowell Colony to complete the work, and it premiered with Beach at the piano in New York on 15 January 1939. In this work, according to critics, “Beach artfully combines French modernism with late Romanticism and elements of American folklore. The transparency and lightness are reminiscent of Ravel, whereas the major emotional intensification later in the movement tends more to evoke Rachmaninoff.” Showcasing her evolution as a composer, Beach sounds a compact style with elements taken from French impressionism and her own unique American voice.

Amy Beach: Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 150 (Trio des Alpes)

Phyllis Tate

English composer Phyllis Tate (1911-1987) started composing during her teenage years. She formerly studied composition with Harry Farjeon at the Royal Academy of Music and wrote an operetta, songs, a string quartet, a violin sonata, a cello concerto and a symphony. In addition, she also wrote and arranged commercial light music under the pseudonyms Max Morelle or Janos. Highly self critical, Tate destroyed almost all her pre-war music, and acknowledged her Saxophone Concerto of 1944 as her first work. “She was often attracted by the sounds and textures of unusual combinations of instruments,” and later in life wrote much music for amateur performers and children. Tate believed that music should entertain and give pleasure. She wrote, “I must admit to having a sneaking hope that some of my creations may prove to be better than they appear. One can only surmise and it’s not for the composer to judge. All I can vouch is this: writing music can be hell; torture in the extreme; but there’s one thing worse; and that is not writing it.”

© British Music Collection

After hearing her play at a lunch concert one day, Dame Ethel Smyth remarked, “At last I have heard a real woman composer!” Tate explored a wide variety of formal structures and harmonic language, “and her elegant and expressive music is always clear and accessible.” The three movements of her Triptych date from 1954 and according to a contemporary review disclose “one of the most important hall-marks of a composer, inventive imagination to a high degree. These are not miniatures, but extended works skillfully developed… The writing throughout is basically harmonic, though there is a brief excursion in loose fugal manner.” Tate once related “my professor was exceedingly upset about this; once maternity takes hold, and that in marriage is inescapable, that’s the end of your composing. True, we did indeed produce one S and one D as the dictionaries say, but oddly enough my output appeared to increase.”

Phyllis Tate: Triptych (Clare Howick, violin; Sophia Rahman, piano)

Nadia Boulanger

A noted composer once wrote, “As far as musical pedagogy is concerned—and by extension of musical creation—Nadia Boulanger is the most influential person who ever lived.” As a teacher, Boulanger greatly influenced several generations of young composers. She taught in music academies including Juilliard, the Yehudi Menuhin School, the Royal College of Music and countless others, but her principle base was her family flat in Paris. For over seven decades, it became the shining beacon for aspiring composers from around the world. Aaron Copland had initial reservations about “studying with a woman,” but soon found her instruction much to his liking. “This intellectual Amazon,” he writes, “is not only familiar with all music from Bach to Stravinsky, but is prepared for anything worse in the way of dissonance.”

Stravinsky and Nadia Boulanger, 1937

In deep gratitude to his teacher, Copland later wrote, “I shall count our meeting the most important of my musical life. Whatever I have accomplished is intimately associated in my mind with those early years, and with what you have since been as inspiration and example.” And let’s not forget that Boulanger was the first woman to conduct many major orchestras in America and Europe, leading world premier performances by Copland, Stravinsky, and countless others.

House of Nadia (1887-1979) and Lili (1893-1918) Boulanger

at No 3 Place Lili-Boulanger

Surprisingly, Nadia Boulanger believed that she had no particular talent as a composer. She did study at the Paris Conservatoire with Gabriel Fauré and her cantata “La Sirène” took second place in the Prix de Rome competition. Boulanger’s works as a solo composer include over 30 songs, chamber music and a Fantaisie variée for piano and orchestra. Her musical language has been described as “highly chromatic, though always tonally based, and Debussy’s influence is apparent in her fondness for modally-inflected melodic lines and parallel chord progressions.” Boulanger stopped composing in the early 1920s to follow her pedagogical calling, but her compositional legacy does include the delightful 3 pieces for cello and piano. Arranged in 1914, the pieces were originally written for organ in 1911, but her cello version has since become more popular.

Nadia Boulanger: 3 Pièces (Matt Haimovitz, cello; Mari Kodama, piano)

Liu Zhuang

Born in Shanghai, Liu Zhuang (1932-2011) initially studied piano with her father and entered the Shanghai Conservatory in 1950 to study harmony, counterpoint, orchestration and composition with Ding Shande, Sang Tong and Den Erjin. After completing her postgraduate studies, she taught composition at the Shanghai Conservatory and at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. In 1970, she was appointed professional composer to the Central Philharmonic Society in Beijing. Liu also was Asian scholar-in-residence at Syracuse University, and her compositions include symphonic works, songs and chamber music. Her music is “technically accomplished and characterized by clarity of structure and poetic expression, and unfolds in a style that paired classical modernism with the melodic contours and harmonies of traditional Chinese music.”

According to the composer, “Wind through Pines describes the tranquility of a night in which the wind blows through a pine forest, explores tone colors of traditional Chinese instruments through modern instruments. The title refers to ancient poetic rhythms in terms of style and form—a sonic exploration of the poetry of music. The piano is prepared to sound like a Ching, a unique ancient plucked instrument. The flute represents the Xiao, a low-pitched Chinese wind instrument. Utilizing overtones and harmonies, the cello serves as unfixed tone, both dotted and solid touch. The piece is free-form, but not formless, like Chinese calligraphy, or when reading a poem with some words exaggerated.”

Please join us next time for one more episode of chamber music composed by women, including works by Maier-Röntgen, La Guerre, Price, Frank, and Pejačević.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Liu Zhuang: Wind Through Pines (John Oberbrunner, flute; George Macero, cello; Steven Heyman, piano)