Carl Nielsen

The tale of the Greek god Pan and the nymph Syrinx is a tale of unrequited love and the invention of a musical instrument. After doing readings in Ovid’s Metamorphses, the Danish composer Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) took up the take of the lascivious god and the fleeing nymph in his symphonic poem Pan og Syrinx (Pan and Syrinx).

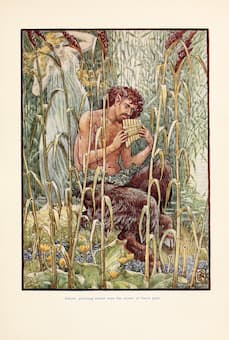

Walter Crane: Pan and his syrinx (ca. 1911)

In Ovid’s story, Pan, the god of the wild, saw the nymph Syrinx. He pursued her and she fled, not waiting to hear his compliments. She invoked the help of her sisters, the naiads, and they changed her into a reed, just as Pan reached out to grasp her. The wind, flowing over the reeds made a murmuring noise and, entranced with the sound and not knowing which reed she had become, Pan cut seven reeds and fashioned an instrument out of them, fastening it together with wax. Known as a syrinx, or pan-pipes, the instrument was henceforth the constant companion of the god and became one of his identifying characteristics.

Pál Szinyei Merse: Faun and Nymph (1868)

(Hungarian National Gallery)

In tales of Pan, the flute is the traditional instrument representing the goat-footed god. In Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, the faun, another goat-footed mythological creature who plays the syrinx, the flute is the instrument that represents the faun and his caprices. The flute stands for the syrinx, as pan-pipes aren’t instruments of the symphonic orchestra.

In Nielsen’s symphonic poem, the wind instruments come to the fore, with the melancholic sound of the English horn contrasting with the higher sound of the clarinet and the flute. The work opens against a background of rustling strings with the flute voice emerging from the background. As the chase progresses, the xylophone and the tambourine lead the percussion. Through the work, the tension rises, reaching a bright climax with full percussion. The work ends as it began – with shimmering violins and a solo flute and a cello that fades away at the end.

Carl Nielsen: Pan og Syrinx (Pan and Syrinx), Op. 49, FS 87 (City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra; Simon Rattle, cond.)

Nielsen’s work received its premiere in 1918 and was immediately called “Debussy-esque” as the critics heard many reflections of the French composer’s impressionistic style of 20 years earlier. Yet, the work is a harbinger of Nielsen’s own style, here demonstrating the upcoming change of style that would take place between his Fourth Symphony (1916) and his Fifth Symphony (1921) where he showed development in his approach to timbre and texture.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter