Europeans had been importing porcelain, silk and lacquer goods from China and Japan ever since the 17th century. At the dawn of the 18th century, European craftsmen and designers were actively imitating Oriental designs, creating their own fanciful versions of the East. Chinoiserie, as it became known, took inspiration from exotic images of far-away China and decorated objects with Chinese figures, landscapes, pagodas, birds and dragons. However, inspiration did not only flow from objects and paintings, but also from literature. The collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales One Thousand and One Nights, or more commonly known as Arabian Nights in the English language, was first published in Venice in 1720. The Venetian dramatist and librettist Carlo Goldoni introduced The Persian Bride in 1753, and his bitter rival Pietro Chiari countered with The Chinese Slave of 1754. It is hardly surprising that Pietro Metastasio, the most important writer of opera seria libretti, decided to join the frenzy for exotic cultural goods from the Orient.

Europeans had been importing porcelain, silk and lacquer goods from China and Japan ever since the 17th century. At the dawn of the 18th century, European craftsmen and designers were actively imitating Oriental designs, creating their own fanciful versions of the East. Chinoiserie, as it became known, took inspiration from exotic images of far-away China and decorated objects with Chinese figures, landscapes, pagodas, birds and dragons. However, inspiration did not only flow from objects and paintings, but also from literature. The collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales One Thousand and One Nights, or more commonly known as Arabian Nights in the English language, was first published in Venice in 1720. The Venetian dramatist and librettist Carlo Goldoni introduced The Persian Bride in 1753, and his bitter rival Pietro Chiari countered with The Chinese Slave of 1754. It is hardly surprising that Pietro Metastasio, the most important writer of opera seria libretti, decided to join the frenzy for exotic cultural goods from the Orient.

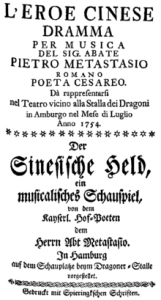

Johann Adolf Hasse: L’Eroe Cinese (The Chinese Hero)

For his L’Eroe Cinese (The Chinese Hero) Metastasio consulted an episode of ancient Chinese imperial history “La storia Tchao-kong” related in a popular Jesuit compilation of 1735. Based on a drama by the Chinese poet Hi-Him-Siang, it was translated into French by Joseph di Primare. The story concerns the Chinese Emperor Li-Vang, whose life was saved when a court minister sacrificed his own son to an angry mob and took the royal infant to safety. In Act I we learn that the anonymous prince Si-veng and Li-sing, a captive Tartar princess, are in love. They despair when her father sends word that she must marry the unknown heir to the Chinese throne. With this opportunity for an alliance with the Tartars, Si-veng is pressured to reveal his true identity, but he declines. In Act II, Si-veng prepares to flee but Le-ang, who substituted his own son Min-ti, bids him to remain silent while he departs to explain everything to Li-sing. Meanwhile Al-sing, an old man who found Min-ti wrapped as a royal baby and raised him in the belief that he was the true heir, informs Si-veng. Si-veng is thrown into confusion, while Li-sing delights at Le-ang’s revelation. In Act 3, Si-veng departs to suppress an insurrection, supposedly led by Min-ti. Challenged by Le-ang, Min-ti reveals that he is the true heir, but is corrected. Once he learns of Si-veng’s mission, he rushes to his friend’s aid. Rumors of Si-veng’s death are dispelled by his arrival with Si-veng, who is now officially identified.

For his L’Eroe Cinese (The Chinese Hero) Metastasio consulted an episode of ancient Chinese imperial history “La storia Tchao-kong” related in a popular Jesuit compilation of 1735. Based on a drama by the Chinese poet Hi-Him-Siang, it was translated into French by Joseph di Primare. The story concerns the Chinese Emperor Li-Vang, whose life was saved when a court minister sacrificed his own son to an angry mob and took the royal infant to safety. In Act I we learn that the anonymous prince Si-veng and Li-sing, a captive Tartar princess, are in love. They despair when her father sends word that she must marry the unknown heir to the Chinese throne. With this opportunity for an alliance with the Tartars, Si-veng is pressured to reveal his true identity, but he declines. In Act II, Si-veng prepares to flee but Le-ang, who substituted his own son Min-ti, bids him to remain silent while he departs to explain everything to Li-sing. Meanwhile Al-sing, an old man who found Min-ti wrapped as a royal baby and raised him in the belief that he was the true heir, informs Si-veng. Si-veng is thrown into confusion, while Li-sing delights at Le-ang’s revelation. In Act 3, Si-veng departs to suppress an insurrection, supposedly led by Min-ti. Challenged by Le-ang, Min-ti reveals that he is the true heir, but is corrected. Once he learns of Si-veng’s mission, he rushes to his friend’s aid. Rumors of Si-veng’s death are dispelled by his arrival with Si-veng, who is now officially identified.

Metastasio finished his libretto in 1752, and it was first staged to music of Giuseppe Bonno in the spring of 1753. The performance took place in the theater of the Schönbrunn Vienna residence, in the presence of king Francis I of Lorraine and empress Maria Theresa of Austria. Metastasio’s libretto proofed immediately popular and Johann Adolf Hasse premiered his musical setting on 7 October 1753 for the court of Frederick the Great. Such was the fascination with the Orient that throughout the eighteenth century almost 20 musical settings of this particular Metastasio libretto were composed by Galuppi, Perez, Conforti, Lenzi, Ballabene, Piazza, Uttini, Giordani, Majo, Sacchini, Colla, Mango, Bertoni, Bachschmidt, Checchi, Portogallo, Cimaroso, and Rauzzini. L’eroe cinese enjoyed numerous showings in at least twenty-four cities, including Munich and London, in the period from 1752 to 1784. Lots of colorful operas to explore, don’t you agree?