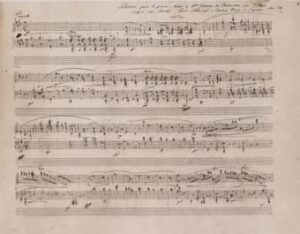

Chopin: Waltz Op. 18

Chopin did not gain an international reputation as a composer until 1833. And while his reception was generally positive, he certainly had his detractors. The influential editor and critic Ludwig Rellstab writes, “In his dances the author satisfies the passion of writing affectedly and unnaturally to a loathsome excess. He is indefatigable, and I might say inexhaustible in his search for ear-splitting discords, forced transitions, harsh modulations, and ugly distortions of melody and rhythm.” We can safely assume that Emma and Laura Horsford disagreed with Rellstab’s assessment. They were the daughters of General George Horsford, who had been Lieutenant Governor of the Bermudas between 1812 and 1814. The family subsequently moved to Paris and daughters Emma and Laura became students of Chopin. He dedicated his Opus 12 “Variations brillantes on a rondo from Halévy’s Ludovic to Emma, and his probably most famous waltz—the E-flat Op. 18—to Laura. Laura must really have liked the Chopin waltzes, as he dedicated a further dance, Opus 70, No.1, to her as well.

Frédéric Chopin: Waltz in E flat Major, Op. 18

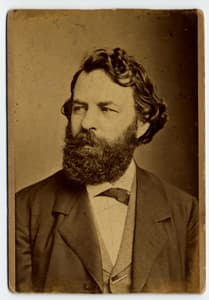

Ferdinand Hiller

Chopin wrote to his friends in Poland in 1831. “Hiller is an immensely talented fellow – a former pupil of Hummel – whose concerto and Symphony produced a great effect three days ago. He’s on the same lines as Beethoven, but a man full of poetry, fire, and spirit.” Ferdinand Hiller originally hailed from Frankfurt, but based himself in Paris from 1828 to 1835. He quickly made friends with Cherubini, Meyerbeer, Rossini, Berlioz, Liszt, Kalkbrenner and Chopin. And he played on the first Chopin concert in Paris on 25th February 1832. Even more astonishingly, he performed Bach’s Concerto for 3 pianos together with Liszt and Chopin. Chopin wrote of Hiller, “a boy of great talent, full of poetry, passion, and spirit.” For a while, Hiller and Chopin became inseparable at social events. Hiller was with Chopin on the fateful day he met George Sand, and they also visited Felix Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn noted his two visitors “suffer somewhat from the Parisian mania for despair and emotional exaggeration.” Hiller eventually moved to Cologne, but not before Chopin dedicated his Op. 15 Nocturnes to his close friend.

Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne in F sharp major, Op. 15, No. 2 (Samson François, piano)

Chopin: Scherzo Op. 54

For over five months of the year, roughly from October or November until May, Frédéric Chopin received an average of five students a day. Each lesson theoretically lasted between 45 minutes and an hour, but frequently it stretched over several hours in succession. His lessons were in high demand, and they were very expensive. Chopin did not accept beginners or children, with the exception of certain prodigies, and he was difficult to approach as he was always surrounded and protected by enthusiastic friends. To be sure, Chopin had some exceptional students, among them the sisters Jeanne and Clothilde de Caraman. He enthusiastically once said to Jeanne, “I give you carte blanche to play all my music. There is in you this vague poetry that is needed to understand it.” Chopin, however, made a rather big mess with the dedication of his 4th Scherzo, Op. 54. The German edition was dedicated to Jeanne, but in the last minute he decided to dedicate the Paris edition to Clothilde. His decision came too late as the title page with Jeanne’s name had been printed already. A more than clumsy attempt to alter the page was too embarrassing, and a completely new title page had to be printed.

Frédéric Chopin: Scherzo No. 4, Op. 54 (Mitsuko Uchida, piano)

Julian Fontana

Julian Fontana (1810-1869) studied music at the University of Warsaw, where he met Frédéric Chopin. They became very close friends and even performed in public together. Fontana left Warsaw in 1831, after the November Uprising, and he settled in Hamburg before becoming a pianist and teacher in Paris in 1832. Unsurprisingly, the two friends reconnected, and starting in 1835 Fontana became Chopin’s copyist and personal secretary. Fontana produced about 50 manuscript copies, which served as the foundations for French, English and German editions of Chopin’s music. In addition, Chopin delegated his musical interests to Fontana, who negotiated with publishers and corrected manuscripts for print, even suggesting changes to the musical text. In 1855, Fontana published a collection of Chopin’s unpublished manuscripts under the opus numbers 66 to 73. And he added 16 of Chopin’s Polish Songs as Op. 74 in 1859. And as you might know, the “Military” Polonaise Op. 40 is dedicated to Julian Fontana.

Frédéric Chopin: Polonaise in A Major, Op. 40, No. 1 (Arthur Rubinstein, piano)

Auguste Franchomme

When Chopin arrived in Paris he quickly struck up a close friendship with the cellist and composer Auguste Franchomme. Franchomme was the appointed court cellist who held first chair in several Parisian orchestras, and at age 20 was one of the founders of the Conservatory Concerts. He also dabbled in composition, and during his long career a number of important composers wrote concertos and other pieces for him. Their first important collaboration was the Grand Duo Concertant, a work canvassing themes from Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le Diable. It proofed popular, and the Parisian publisher Schlesinger subsequently agreed to publish all of Chopin’s previous and future works. And that eventually included the sonata for cello and piano, opus 65. They performed the last three movements at Chopin’s last concert in 1848. Franchomme helped Chopin to assemble a thematic catalogue of his compositions, took him to his relatives in the country for convalescence, and eventually looked after Chopin’s financial accounts. Providing a final service for his friend, Franchomme was one of the bearers of Chopin’s coffin.

Frédéric Chopin: Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 65 (Natalie Clein, cello; Charles Owen, piano)

Jane Stirling

The Scottish amateur pianist Jane Stirling was six years Chopin’s senior when he took her on as a piano student. He regarded her as “a middle-aged spinster,” but Stirling had high hopes of replacing George Sand in Chopin’s affections. With Chopin’s permission, Stirling became his agent and business manager, and she arranged a trip to England and Scotland for him. His health was deteriorating fast, and he was making very little money. Stirling kept arranging concerts in Manchester and Glasgow, and rumors of a forthcoming marriage reached Paris and Warsaw, with Chopin famously stating, “I am closer to a coffin than a marriage bed.” When he returned to London he weighed less than 45 kg, and although he managed one final concert for the Friends of Poland, his doctors were well aware that he was in the terminal stages of his illness and recommended that he return to Paris as soon as possible. Chopin died in October 1849, and Jane Stirling remained a devoted disciple until her death 10 years later. And just in case you didn’t know, Chopin dedicated his two Nocturnes Opus 55 to Stirling.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne in F minor, Op. 55, No. 1

An exceptional account of the people who meant most to Chopin.