“A Gentleman Is Someone Who Knows How to Play the Banjo and Doesn’t”

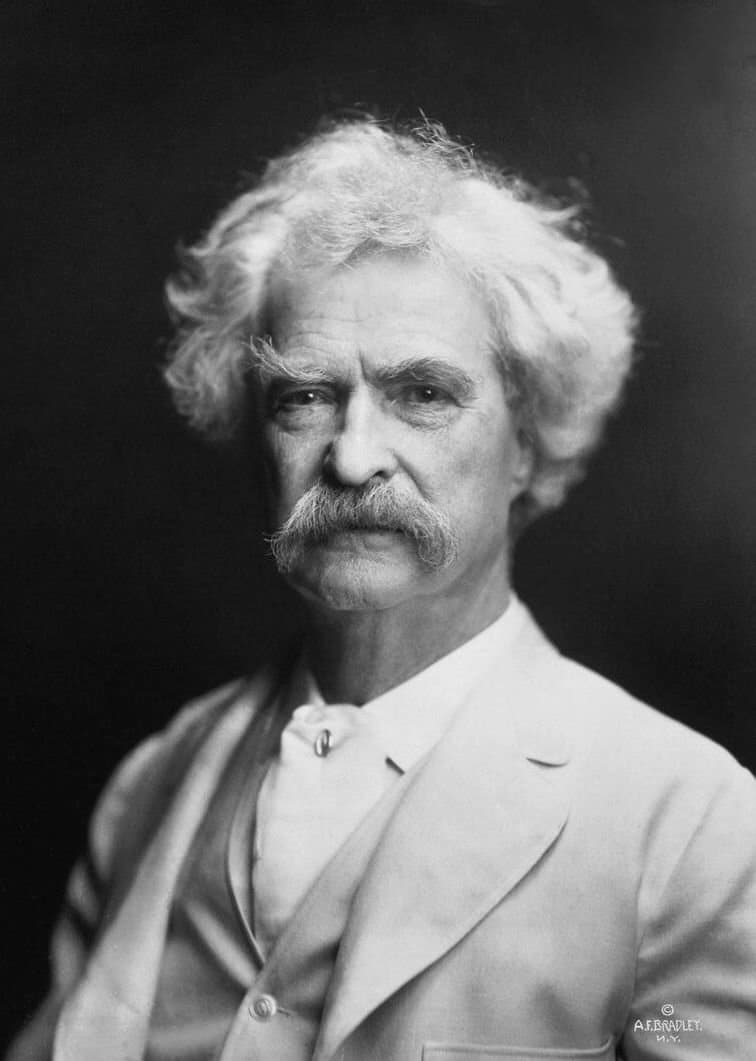

Mark Twain

Considered the “greatest humorist the United States has produced,” Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known as Mark Twain (1835-1910), had an uneasy relationship with classical music. He wrote in his diary that he would “rather have my leg amputated than listen to classical music.” When he declared, “Wagner’s music is better than it sounds,” he gave voice to his intense dislike of opera. “I have attended opera,” he writes, “whenever I could not help it, for fourteen years now; I am sure I know of no agony comparable to the listening of an unfamiliar opera. I am enchanted with the airs of ‘Trovatore’ and other old operas, which the hand-organ and the music box have made entirely familiar to my ear. I am carried away with delighted enthusiasm when they are sung at the opera. But oh, how far between they are! And what long, arid, heartbreaking and head-aching ‘between-time’ of that sort of intense but incoherent noise which always so reminds me of the time the orphan asylum burned down.” As he tellingly wrote, “we often feel sad in the presence of music without words; and often more than that in the presence of music without music.” In his wildest dreams, Mr. Clemens could not have foreseen that his daughter Clara—a competent pianist and accomplished singer—would marry the pianist, composer, and eventual conductor Ossip Gabrilowitsch.

Ossip Gabrilowitsch: Theme and Variation for Piano, Op. 4 (Tobias Bigger, piano)

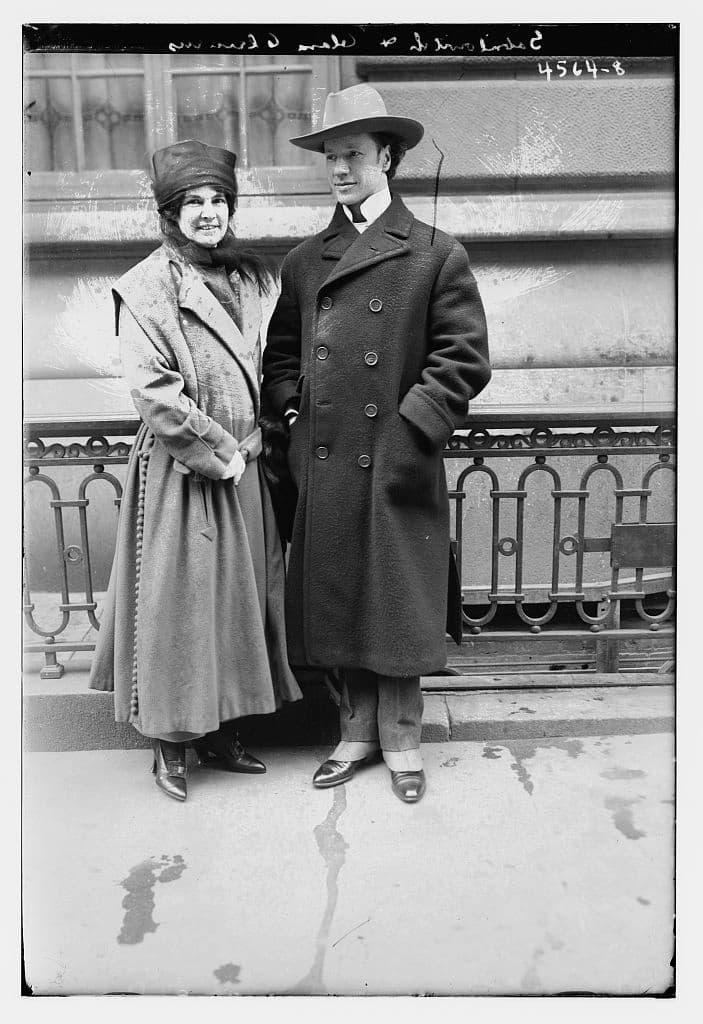

Clara Clemens and Ossip Gabrilowitsch

Mark Twain liked to project the American persona of a witty Mississippi River denizen. In reality, however, he was a man of the world. For most of the 1890s, he lived in Europe, and he was reasonably versed in German, French, and Italian. He was treated like an international celebrity in Vienna, and when Clara asked to bring her future husband Ossip Gabrilowitsch home for dinner, her father consented “provided that Gabrilowitsch promise not to play the piano.” Clara remembered, “my father was always ill at ease among the musical people, for they were concerned with a form of art that left him at that time wholly unmoved, and sometimes actually uncomfortable. The most that he got out of his association with these people was great admiration for their memory and the nimbleness of their fingers. He was sure that Leschetizky was the greatest pianist who ever lived and he was never hesitant about expressing his amazement that human hands could do what he did, and the human mind remembers how to do it.” As you might have guessed by now, the union of Clara and Ossip was forged in the piano studio of the great pianist and pedagogue Leschetizky.

Ossip Gabrilowitsch: Melodie in E minor, Op. 8 (Stephen Hough, piano)

Clara Clemens and Ossip Gabrilowitsch

Ossip Gabrilowitsch (1878-1936) initially entered the St Petersburg Conservatory at the age of ten and studied with the great Anton Rubinstein. He won the coveted Rubinstein Prize at age sixteen, and he moved to Vienna to further his studies with Leschetizky. Leschetizky considered him one of the greatest representations of his teaching, and he also greatly valued him as a composer. Remembering his time with Leschetizky, Gabrilowitsch wrote, “what Leschetizky was concerned about was the meaning of a composition as a whole, its poetic message and musical construction, then the beauty of tone with which it could be expressed…” Clara and her father, meanwhile, lived in Vienna for roughly 20 months between 1897 and 1899 so Clara could study piano with Leschetizky as well. Initially, Ossip and Clara did not seem to get on famously, and their courtship was seriously rocky at time. They were engaged twice, but both times the engagement was broken. He once wrote to her “I renounce our friendship,” but eventually they were married in Connecticut in 1909.

Ossip Gabrilowitsch: 3 Piano Pieces, Op. 2 (Margarita Glebov, piano)

Marriage of Clara Clemens and Ossip Gabrilowitsch

The couple, together with their young daughter established a base in Munich, and Ossip began to develop his credentials as a conductor. When war broke out between Germany and Russia in the summer of 1914, Ossip was arrested and accused of being a spy. Clara remembered, “a soldier suggested to her that if only your husband will think to say that he was about to become a naturalized German! Otherwise, you know how little justice is practiced in times of war.” When Clara said this would never happen, she was told: “Then, I don’t know what can save him.” Ossip was saved by the intervention of Bruno Walter, who talked a young cleric into offering support. That young cleric later became Pope Pius XII. After Ossip’s release, the family fled to New York and he first conducted there in 1916. Two years later, he was appointed conductor of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, a post he held until his death from cancer in 1936. During the roaring 1920s, Detroit was awash with automotive money, and “Ossip and Clara were the prince and princess of high culture.” They lived in a 10,000-square-foot home in the Boston-Edison neighborhood, “and the houseman brushed their cat every morning and filled the inkwells each Monday.” After Ossip’s death, Clara married the Russian conductor Jacques Alexandria Samossoud, and she died in San Diego at the age of 88.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ossip Gabrilowitsch: Caprice Burlesque, Op. 3 (Stephen Hough, piano)