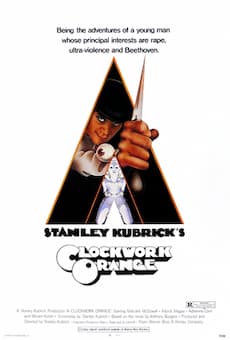

Some say that feminist musicology started at the movies, and that it all kicked off with Stanley Kubrick’s dystopian crime film “A Clockwork Orange” of 1971. The central character Alex is a charismatic and antisocial delinquent who is interested in classical music, specifically the music of Beethoven. He leads a small ultra-violent gang, commits rape, theft and other horrific crimes. Once he is captured, he agrees to become a test subject for the Minister of the Interior. As part of an experimental aversion therapy for rehabilitating criminals, Alex is strapped to a chair. His eyes are clamped open and he is injected with drugs. He is then forced to watch films of sex, violence and rape accompanied by the music of his favorite composer Ludwig van Beethoven. After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, but the music of Beethoven becomes pure torture. The connection between rape and Beethoven’s 9th stipulated in the film subsequently became a hot topic in feminist musicology, with one academic writing that Beethoven’s 9th symphony represents the “throttling murderous rage of a rapist incapable of attaining release.” It has to be said, however, that there is no evidence that Beethoven ever committed a rape or even harbored an urge to do so.

Some say that feminist musicology started at the movies, and that it all kicked off with Stanley Kubrick’s dystopian crime film “A Clockwork Orange” of 1971. The central character Alex is a charismatic and antisocial delinquent who is interested in classical music, specifically the music of Beethoven. He leads a small ultra-violent gang, commits rape, theft and other horrific crimes. Once he is captured, he agrees to become a test subject for the Minister of the Interior. As part of an experimental aversion therapy for rehabilitating criminals, Alex is strapped to a chair. His eyes are clamped open and he is injected with drugs. He is then forced to watch films of sex, violence and rape accompanied by the music of his favorite composer Ludwig van Beethoven. After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, but the music of Beethoven becomes pure torture. The connection between rape and Beethoven’s 9th stipulated in the film subsequently became a hot topic in feminist musicology, with one academic writing that Beethoven’s 9th symphony represents the “throttling murderous rage of a rapist incapable of attaining release.” It has to be said, however, that there is no evidence that Beethoven ever committed a rape or even harbored an urge to do so.

A Clockwork Orange: Beethoven, “9th Symphony”

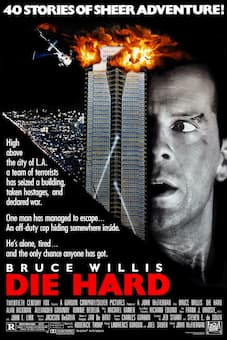

Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, and particularly the concluding “Ode to Joy” seem like an uneasy fit for an action blockbuster movie. But that’s exactly what happened in one of the greatest actions films, “Die Hard” from 1988. Based on the 1979 novel “Nothing Lasts Forever,” it tells the story of police detective John McClane, portrayed by Bruce Willis, who is caught up in a terrorist takeover of a Los Angeles skyscraper while visiting his estranged wife. Director John McTiernan had seen Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” and wanted to include the “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. However, the hired composer Michael Kamen objected, “not wanting to tarnish Beethoven’s music in an action movie and offered to used the music of Richard Wagner instead.” In the end, they agreed to use Beethoven, alongside “Singin’ in the Rain,” and “Winter Wonderland” to underscore the villains in the film. If you have a chance to view “Die Hard,” also watch out for Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3.

Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, and particularly the concluding “Ode to Joy” seem like an uneasy fit for an action blockbuster movie. But that’s exactly what happened in one of the greatest actions films, “Die Hard” from 1988. Based on the 1979 novel “Nothing Lasts Forever,” it tells the story of police detective John McClane, portrayed by Bruce Willis, who is caught up in a terrorist takeover of a Los Angeles skyscraper while visiting his estranged wife. Director John McTiernan had seen Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” and wanted to include the “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. However, the hired composer Michael Kamen objected, “not wanting to tarnish Beethoven’s music in an action movie and offered to used the music of Richard Wagner instead.” In the end, they agreed to use Beethoven, alongside “Singin’ in the Rain,” and “Winter Wonderland” to underscore the villains in the film. If you have a chance to view “Die Hard,” also watch out for Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3.

Die Hard: Beethoven, “Ode to Joy”

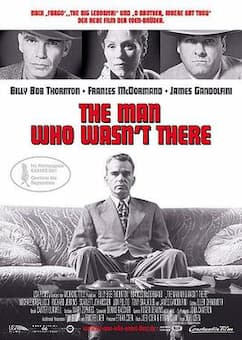

It’s hardly surprising that the multifaceted sound world of Beethoven is prominently featured in countless motion picture. Such is the case in the 2001 crime film titled “The Man Who Wasn’t There.” Set in 1949, Ed Crane is a barber working in the town of Santa Rosa, California. He is married to Doris, a bookkeeper with a drinking problem. A customer is looking for investors for a new technology called dry cleaning, and Ed decides to anonymously blackmailing Doris’ boss Dave, whom he suspects is having an affair with her. Dave embezzles money from his department store to pay the blackmail, and he eventually confronts Ed. Dave attempts to kill Ed, but instead he is fatally stabbed by Ed. Doris is arrested, and hangs herself in her cell. Ed now turns to alcohol, and he regularly visits a friend’s teenage daughter to hear her play the piano. In the end, the whole sordid tale is revealed and Ed is electrocuted, “hoping to see Doris in the afterlife.” The slow movement of Beethoven’s “Pathetique” is used throughout the film, becoming a seemingly knowing and ironic bystander and commentator.

It’s hardly surprising that the multifaceted sound world of Beethoven is prominently featured in countless motion picture. Such is the case in the 2001 crime film titled “The Man Who Wasn’t There.” Set in 1949, Ed Crane is a barber working in the town of Santa Rosa, California. He is married to Doris, a bookkeeper with a drinking problem. A customer is looking for investors for a new technology called dry cleaning, and Ed decides to anonymously blackmailing Doris’ boss Dave, whom he suspects is having an affair with her. Dave embezzles money from his department store to pay the blackmail, and he eventually confronts Ed. Dave attempts to kill Ed, but instead he is fatally stabbed by Ed. Doris is arrested, and hangs herself in her cell. Ed now turns to alcohol, and he regularly visits a friend’s teenage daughter to hear her play the piano. In the end, the whole sordid tale is revealed and Ed is electrocuted, “hoping to see Doris in the afterlife.” The slow movement of Beethoven’s “Pathetique” is used throughout the film, becoming a seemingly knowing and ironic bystander and commentator.

The Man Who Wasn’t There: Beethoven, “Pathetique”

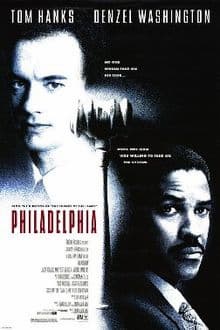

The 1993 legal drama “Philadelphia” was the first mainstream Hollywood film to deal with the subject of HIV/AIDS, homosexuality, and homophobia. It features Tom Hanks as Andrew Beckett, the senior associate at the largest corporate law firm in Philadelphia, and Denzel Washington as his personal injury attorney. Becket has been hiding his homosexuality and his status as an AIDS patient from the other members of the firm, and works from home to disguise the advancing disease. There is a mix-up concerning some important trial papers, and the firm dismisses Beckett. Beckett suspects that someone deliberately hid the paperwork to give the firm an excuse to fire him for his diagnosis with AIDS and his sexuality. Attorney Joe Miller finally takes on the case, and the jury votes in his favor, awarding him damages for pain and suffering and punitive damage. Beckett’s health is rapidly failing, and he peacefully dies in hospital. One of the most touching scenes is Beckett’s monologue and explanation of the aria “La Mamma Morta,” sung by Maria Callas.

The 1993 legal drama “Philadelphia” was the first mainstream Hollywood film to deal with the subject of HIV/AIDS, homosexuality, and homophobia. It features Tom Hanks as Andrew Beckett, the senior associate at the largest corporate law firm in Philadelphia, and Denzel Washington as his personal injury attorney. Becket has been hiding his homosexuality and his status as an AIDS patient from the other members of the firm, and works from home to disguise the advancing disease. There is a mix-up concerning some important trial papers, and the firm dismisses Beckett. Beckett suspects that someone deliberately hid the paperwork to give the firm an excuse to fire him for his diagnosis with AIDS and his sexuality. Attorney Joe Miller finally takes on the case, and the jury votes in his favor, awarding him damages for pain and suffering and punitive damage. Beckett’s health is rapidly failing, and he peacefully dies in hospital. One of the most touching scenes is Beckett’s monologue and explanation of the aria “La Mamma Morta,” sung by Maria Callas.

Philadelphia: Umberto Giordano, “La Mamma Morta” from Andrea Chénier

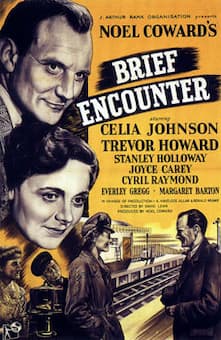

Romantic dramas frequently feature romantic music. And it doesn’t get any more romantic than the 1945 film “Brief Encounter” based on a screenplay by Noël Coward. Laura Jesson is a respectable middle-class woman in an affectionate but rather dull marriage. Every Thursday she goes shopping and catches a movie at the cinema. One day, on her way home she meets the general practitioner Alex Harvey who works as a consultant at the local hospital. Alex is married as well, and their casual relationship soon develops into something deeper. They soon realize, however, that an affair or a future together is impossible. Alex accepts a job in South Africa, and their final meeting occurs in the railway station to the heart-wrenching strains of Rachmaninoff’s 2nd piano concerto. If you ask me, the music is a perfect fit for this ill-fated love story.

Romantic dramas frequently feature romantic music. And it doesn’t get any more romantic than the 1945 film “Brief Encounter” based on a screenplay by Noël Coward. Laura Jesson is a respectable middle-class woman in an affectionate but rather dull marriage. Every Thursday she goes shopping and catches a movie at the cinema. One day, on her way home she meets the general practitioner Alex Harvey who works as a consultant at the local hospital. Alex is married as well, and their casual relationship soon develops into something deeper. They soon realize, however, that an affair or a future together is impossible. Alex accepts a job in South Africa, and their final meeting occurs in the railway station to the heart-wrenching strains of Rachmaninoff’s 2nd piano concerto. If you ask me, the music is a perfect fit for this ill-fated love story.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Brief Encounter: Rachmaninoff, “Piano Concert No. 2”