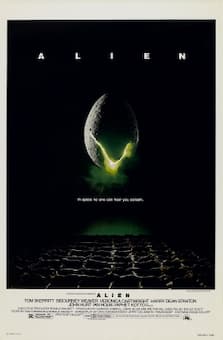

The music of American composer Howard Hanson entered popular consciousness when excerpts of his 2nd Symphony were used in the 1979 sci-fi horror movie “Alien.” Although the musical excerpt was used without permission, the composer decided not to fight the infringement in court. The movie itself was a resounding success, and it spawned sequels and a media franchise featuring novels, comic books, video games and toys. The plot features a commercial space ship returning to earth when they intercept an emergency transmission. Landing on an alien moon, the crew discovers a chamber containing hundred of large, egg-like objects. When a crewmember touches the egg, a creature jumps out and attaches itself to the face of the explorer. Eventually a small alien creature burst from the explorer’s chest and escapes into the ship. The crew attempts to located the now fully-grown creature, but they are killed one by one. In the end, it is left to Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver, to kill the pesky creature. To the sounds of Hanson’s richly orchestrated neo-romantic music, she calmly dispatches the monster and places herself into stasis for the long trip back to Earth.

The music of American composer Howard Hanson entered popular consciousness when excerpts of his 2nd Symphony were used in the 1979 sci-fi horror movie “Alien.” Although the musical excerpt was used without permission, the composer decided not to fight the infringement in court. The movie itself was a resounding success, and it spawned sequels and a media franchise featuring novels, comic books, video games and toys. The plot features a commercial space ship returning to earth when they intercept an emergency transmission. Landing on an alien moon, the crew discovers a chamber containing hundred of large, egg-like objects. When a crewmember touches the egg, a creature jumps out and attaches itself to the face of the explorer. Eventually a small alien creature burst from the explorer’s chest and escapes into the ship. The crew attempts to located the now fully-grown creature, but they are killed one by one. In the end, it is left to Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver, to kill the pesky creature. To the sounds of Hanson’s richly orchestrated neo-romantic music, she calmly dispatches the monster and places herself into stasis for the long trip back to Earth.

Alien: Hanson, “Symphony No. 2”

The fifth installment of the “Mission Impossible” series “Rogue Nation” was released in 2015. Tom Cruise once again plays the agent Ethan Hunt, this time charged with the recovery of a package of nerve gas. He does succeed, but learns that a terrorist syndicate is operating behind the scenes. After he is nearly killed by a Syndicate operative, he spends six months trying to track the Syndicate. In the end, according to form, all conflicts are resolved. One of the most memorable scenes takes place on the rooftop, and in the rafters of the Vienna State Opera. To the sounds of Puccini’s “Nessun dorma,” Hunt is involved in a life or death struggle. The action is as tightly choreographed as any ballet performance, and the entire scene works seamlessly around an actual performance of the opera. For me personally, this is one of the most successful pairing of classical music with cinematography.

The fifth installment of the “Mission Impossible” series “Rogue Nation” was released in 2015. Tom Cruise once again plays the agent Ethan Hunt, this time charged with the recovery of a package of nerve gas. He does succeed, but learns that a terrorist syndicate is operating behind the scenes. After he is nearly killed by a Syndicate operative, he spends six months trying to track the Syndicate. In the end, according to form, all conflicts are resolved. One of the most memorable scenes takes place on the rooftop, and in the rafters of the Vienna State Opera. To the sounds of Puccini’s “Nessun dorma,” Hunt is involved in a life or death struggle. The action is as tightly choreographed as any ballet performance, and the entire scene works seamlessly around an actual performance of the opera. For me personally, this is one of the most successful pairing of classical music with cinematography.

Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, Puccini, “Turandot”

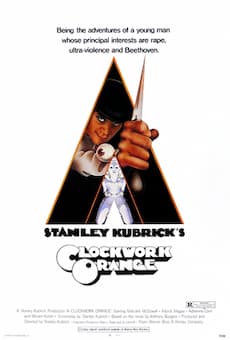

The film director Stanley Kubrick is frequently considered one of the greatest filmmakers in cinematic history. By all account, he was a demanding perfectionist who assumed control over most aspects of the filmmaking process, including music. Jack Nicholson stated “Kubrick listened constantly to music until he discovered something he felt was right or that excited him.” It has even been rumored that Kubrick made his film crew listen to Mozart before starting each day of filming. For Kubrick, music was a vital element in film, not merely in terms of heavy hitting soundtracks but by adding additional layers of meanings. In fact, he frequently uses classical music to change the overall tone of the film. His psychological horror film “The Shining,” based on a novel by Stephen King, first screened in 1980. Jack Torrance, an aspiring writer and recovering alcoholic accepts a position as caretaker of an isolated hotel in the Colorado Rockies. He brings along his wife Wendy and their young son Danny, who has the psychic ability to see into the hotel’s horrific past. A previous winter caretaker went insane and killed his family and himself, and when an enormous winter storm leaves Jack and his family snowbound, things start to quickly unravel. Kubrick incorporates the medieval hymn “Dies Irae” (Day of Judgment), an excerpt by Krzysztof Penderecki, and Bartok’s “Music for String, Percussion, and Celeste” to terrifying effect.

The film director Stanley Kubrick is frequently considered one of the greatest filmmakers in cinematic history. By all account, he was a demanding perfectionist who assumed control over most aspects of the filmmaking process, including music. Jack Nicholson stated “Kubrick listened constantly to music until he discovered something he felt was right or that excited him.” It has even been rumored that Kubrick made his film crew listen to Mozart before starting each day of filming. For Kubrick, music was a vital element in film, not merely in terms of heavy hitting soundtracks but by adding additional layers of meanings. In fact, he frequently uses classical music to change the overall tone of the film. His psychological horror film “The Shining,” based on a novel by Stephen King, first screened in 1980. Jack Torrance, an aspiring writer and recovering alcoholic accepts a position as caretaker of an isolated hotel in the Colorado Rockies. He brings along his wife Wendy and their young son Danny, who has the psychic ability to see into the hotel’s horrific past. A previous winter caretaker went insane and killed his family and himself, and when an enormous winter storm leaves Jack and his family snowbound, things start to quickly unravel. Kubrick incorporates the medieval hymn “Dies Irae” (Day of Judgment), an excerpt by Krzysztof Penderecki, and Bartok’s “Music for String, Percussion, and Celeste” to terrifying effect.

The Shining: Bartok, “Music for String, Percussion, and Celeste”

The life of Australian concert pianist David Helfgott inspired the 1996 Academy Award-winning film “Shine.” Exceptionally talented, Helfgott won a number of prizes before continuing his studies at the Royal College of Music. For his performance of Rachmaninoff’s 3rd piano concerto, Helfgott won the Dannreuther Prize for Best Concert Performance, and the Marmaduke Barton Prize. During his time in London, Helfgott began to show manifestations of schizoaffective disorder. As portrayed in the movie, his behavior becomes increasingly unhinged, and he suffers a mental breakdown. He is admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where he receives electric shock therapy to treat his condition. Helfgott is able to return to Australia, but suffers a relapse and is readmitted to a mental institution. After several years a volunteer recognizes Helfgott, and with the help of his future wife Gillian, David stages a well-received comeback concert, presaging his return to professional music. That comeback concert, unsurprisingly, features Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3.

The life of Australian concert pianist David Helfgott inspired the 1996 Academy Award-winning film “Shine.” Exceptionally talented, Helfgott won a number of prizes before continuing his studies at the Royal College of Music. For his performance of Rachmaninoff’s 3rd piano concerto, Helfgott won the Dannreuther Prize for Best Concert Performance, and the Marmaduke Barton Prize. During his time in London, Helfgott began to show manifestations of schizoaffective disorder. As portrayed in the movie, his behavior becomes increasingly unhinged, and he suffers a mental breakdown. He is admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where he receives electric shock therapy to treat his condition. Helfgott is able to return to Australia, but suffers a relapse and is readmitted to a mental institution. After several years a volunteer recognizes Helfgott, and with the help of his future wife Gillian, David stages a well-received comeback concert, presaging his return to professional music. That comeback concert, unsurprisingly, features Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3.

Shine: Rachmaninoff, “Piano Concert No. 3”

The 2010 historical drama “The King’s Speech” is set at the closing of the British Empire Exhibition. The future King George VI addresses the crowds with a strong stammer. He has been unsuccessfully searching for treatment, and his wife Elizabeth eventually persuades him to see the Australian speech and language therapist Lionel Logue. “Bertie,” as his family calls the future king, initially believes that the therapy is not working. However, Lionel assures him that his new technique—reciting the famous “Hamlet” soliloquy while simultaneously listening to classical music—will eventually produce results. The two men become friends, and when Edward VIII has to abdicate as the result over his prospective marriage to twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson, George VI becomes the new king. He now has to heavily rely on his speech therapist to make his first wartime radio broadcast upon Britain’s declaration of war on Germany in 1939. Accompanying the speech is the second movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. The use of Beethoven is not meant to be ironic, but it parallels King George’s increasing self-confidence.

The 2010 historical drama “The King’s Speech” is set at the closing of the British Empire Exhibition. The future King George VI addresses the crowds with a strong stammer. He has been unsuccessfully searching for treatment, and his wife Elizabeth eventually persuades him to see the Australian speech and language therapist Lionel Logue. “Bertie,” as his family calls the future king, initially believes that the therapy is not working. However, Lionel assures him that his new technique—reciting the famous “Hamlet” soliloquy while simultaneously listening to classical music—will eventually produce results. The two men become friends, and when Edward VIII has to abdicate as the result over his prospective marriage to twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson, George VI becomes the new king. He now has to heavily rely on his speech therapist to make his first wartime radio broadcast upon Britain’s declaration of war on Germany in 1939. Accompanying the speech is the second movement of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7. The use of Beethoven is not meant to be ironic, but it parallels King George’s increasing self-confidence.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

The King’s Speech: Beethoven, “Symphony No. 7”