“I set down a beautiful chord on paper—and suddenly it rusts”

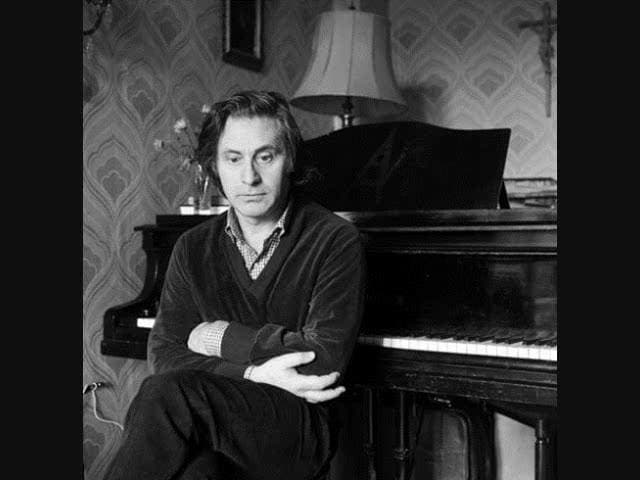

The music of Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998) is marked by an intense expressiveness, an unpredictable flow of ideas, an innate sense of drama, and a natural lyricism. Turning his back on the dissonant sounds of atonal academic modernism, Schnittke favored a synthesis of familiar styles. As he reintroduced traditional elements of musical styles he attempted to close the gap between himself and the listening public. As he once wrote, “The goal of my life is to unify serious music and light music, even if I break my neck in doing so.”

Twenty-five years after his death, it is becoming increasingly clear that Alfred Schnittke “was one of the few composers for whom traditional genres retained their relevance.” But more importantly, Schnittke gave new life to these old forms by squeezing radically different compositional styles, drawn from centuries of music history, into the same composition. His polystylistic approach and construction keep the music in constant dialogue with the past, and it generates extraordinary dramatic power with great audience appeal.

Alfred Schnittke: Sonata for Violin and Piano No. 2, “Quasi una Sonata”

Childhood

Alfred Schnittke was born in Engles, in the Volga-German Republic of the Soviet Union, but he received his earliest musical training in Vienna while his father served there as a translator. As he later wrote, “I felt every moment there to be a link of the historical chain: all was multi-dimensional.”

Alfred Schnittke as a young man

Once the family had moved to Moscow in 1958, Alfred Schnittke completed his graduate work in composition at the Moscow Conservatory and immediately fell into conflict with Soviet doctrine. His oratorio Nagasaki was condemned by the Union of Composers, and throughout this part of his career, he was constantly attacked in official publications. Much of his music was viewed with great suspicion by the Soviet bureaucracy and his First Symphony was effectively banned from performance in 1974.

Alfred Schnittke: Concerto Grosso No. 1 “Rondo”

Film Music

Making his living as a freelance composer, Schnittke wrote for the theatre and for film. In fact, between 1962 and 1984 he composed a total of 66 film scores. These scores offer a variety of simple and eclectic effects, and it is music of economy and sureness of touch. Every mood expresses itself immediately, with no preliminaries. A critic writes, “There is not a note too much.” Concurrently, Schnittke also wrote an extensive number of articles on issues in contemporary music.

As Schnittke later explained, “My musical development took a course similar to that of some friends and colleagues, across piano concerto romanticism, neoclassical academicism, and attempts at eclectic synthesis, and I also took cognizance of the unavoidable proofs of masculinity in serial self-denial. Having arrived at the final station, I decided to get off the already overcrowded train and proceed on foot.”

Alfred Schnittke: Adventures of a Dentist “Suite” (Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; Frank Strobel, cond.)

A New Path

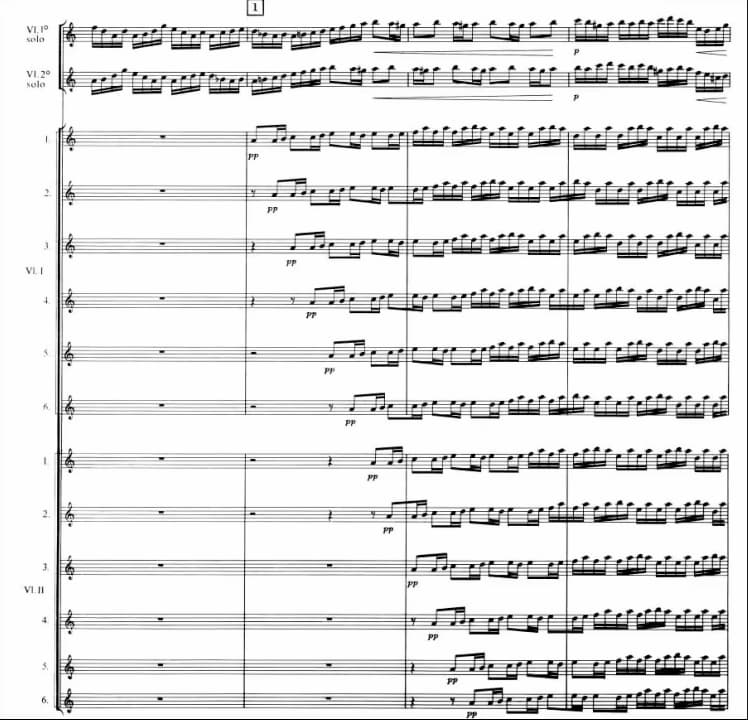

Alfred Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso No. 1

Following the death of his mother in 1972, Schnittke turned to Catholicism for solace. As a biographer writes, “he possessed deeply held beliefs in predestination and mysticism which greatly influenced his music.” Simultaneously, a more liberal political attitude allowed Schnittke to analyze in great detail the music of Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. However, he also studied scores by Stockhausen, Nono, and Ligeti, and he decided to abandon serial composition techniques.

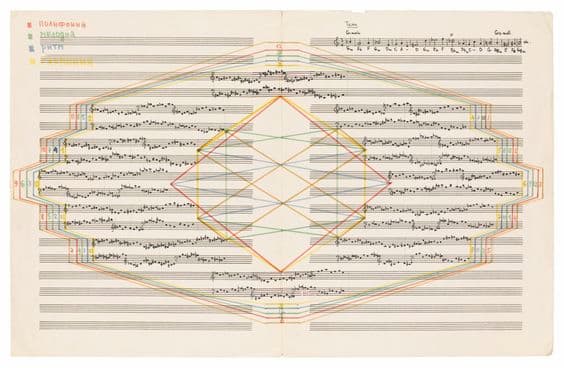

By merging Romanticism, church music, popular and ethnic music with scraps of historical materials, Schnittke creates startling sound vistas. As the composer puts it, “I set down a beautiful chord on paper—and suddenly it rusts.” In essence, the historical musical landmarks of the past are under immediate pressure from the present. Recalling his days in Vienna, Schnittke is particularly fond of metamorphosing sound bites ranging from Haydn to Schubert, and mingling them with rich veins of aggressive dissonances. These stylistic modulations are never arbitrary or random, but describe a progression from chaotic polystylism to heartfelt spirituality.

Alfred Schnittke: Piano Quintet

A World of Quotations

Alfred Schnittke’s Autograph graphic score of the “Cantus perpetuus”

His early music shows the strong influence of his teacher Shostakovich, but for many commentators, Mahler was the central reference point for Schnittke. A biographer saw Mahler as the source of Schnittke’s “sense of irreconcilable conflict,” and as Richard Taruskin writes, “With a bluntness and an immodesty practically unseen since the days of Mahler, Mr. Schnittke tackles life-against-death, love-against-hate, good-against-evil and (especially in the concertos) I-against-the-world.”

In his music, Schnittke often also quoted from composers such as Lassus, Bach, and Mozart, making connections with forms from the past such as the concerto grosso, the waltz and the passacaglia; he employed a mix of styles and techniques, including Russian Orthodox, folk music, Russian nationalist music, contemporary, tonal, atonal, and microtonal, in order to bridge the gap between the present and the past in works with a spiritual, ironic or expressionist slant.

Alfred Schnittke: String Trio (Ensemble Epomeo)

Declining Health

With Gorbachev coming to power in 1985, Alfred Schnittke was finally able to travel more freely and attended performances of his works outside the Soviet Union. Sadly, he began to be affected by health problems, suffering a serious stroke on 19 June, and the composer was pronounced clinically dead three times. He suffered a second stroke in 1991, after he had moved to Hamburg, and his music became more austere and more obviously concerned with mortality. Textures became very ascetic and the number of notes is reduced. “The meaning of his last few compositions is to be found between the notes rather than in the musical text itself.”

Schnittke’s music became tough, dissonant, and discordant, and it was very far removed from the easy-listening experience. In fact, at the first performance of Symphony No. 6 at Carnegie Hall, almost half the audience left before the end. However, to some scholars, “Schnittke’s late works will ultimately be the most influential part of his output.” To be sure, Schnittke was the recipient of numerous international prizes and awards, including the Russian State Prize and awards from Austria, Germany, and Japan.

Alfred Schnittke: Symphony No. 6 “Allegro moderato” (Russian State Symphony Orchestra; Valery Polyansky, cond.)

Death

Gravestone of Alfred Schnittke

Alfred Schnittke died in Hamburg on 3 August 1998 following a fifth stroke. His funeral in Moscow on 10 August 1998, attended by thousands of people, was a tribute of honor and admiration to the greatest Russian composer since Shostakovich. For many critics, “Schnittke was the last genius of the 20th Century. Those wishing to listen to his music will undoubtedly absorb the intense energy of the flow of the music, making it part of their being, part of their thinking, and part of their language.”

Schnittke was a man caught in between different traditions. “Although I don’t have any Russian blood,” he explained, “I am tied to Russia, having spent all my life here. Like my German forebears, I live in Russia and I can speak and write Russian far better than German. But I am not Russian. My Jewish half gives me no peace: I know none of the Jewish languages, but I look like a typical Jew.”

Alfred Schnittke: Three Sacred Hymns

Legacy

One of the most prolific composers of modern times, he became extraordinarily popular in Russia during the 1970s and 80s. As a critic wrote, “his music used to be our language, more perfect than the verbal one.” Performances of his music were important events for Soviet listeners, “for in it they found spiritual values that were absent from everyday life during the endless years of terror, thaw, cold war, and stagnation.”

Schnittke’s “musical vocabulary reveals the difference between the conceivable and the audible. With the passing of time, this vocabulary is changing and transforming from the strikingly individual to the universal; mankind is, as it were, appropriating the achievements of the composer and the music is losing its topical interest.” In some sense, Schnittke’s music has already become a part of the history of music as it expresses the very essence of 20th-century culture.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I truly wish I could somehow obtain an exact chronological list of Schnittke’s works.