What is it about conducting fathers whose sons followed in their footsteps? Many professional musicians sire musical offspring, (myself included) but I was struck by the number of conductors in the bunch and thought you’d like to hear more about them too.

Arvīds and Mariss Jansons

Arvīds and Mariss Jansons: Arvīds was a Latvian conductor who studied the violin at the Conservatory of Liepāja, and composition and conducting at the Conservatory of Riga. He had the honor of being chosen by the great maestro Yevgeny Mravinsky to be his assistant at Leningrad Philharmonic. Arvīds married the lovely singer Iraida. Soon, they were expecting their first child but World War II intervened. Despite being pregnant, she was incarcerated like other Jews in the Riga Ghetto. Somehow, she was smuggled out of the ghetto, and while in hiding, she gave birth to Mariss. After the war Arvīds was appointed to the Latvian Radio Orchestra, followed by the Leningrad Philharmonic as tour conductor, and the Hallé Orchestra. He was a respected teacher and recorded extensively.

Marris began his violin studies with his father and then attended the Leningrad Conservatory. A protégé of Herbert von Karajan, he later became the music director of the Oslo Philharmonic, and the principal guest conductor of the London Philharmonic. Jansons was one of the most respected and widely sought out maestros, winning numerous awards, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic’s New Year’s Eve celebrations, and holding positions with the Pittsburgh Symphony, Bavarian Radio Symphony, and Amsterdam’s famed Concertgebouw. His epic recordings include the symphonies of Mahler and Shostakovich. A much beloved and kind person, he knew his player’s names and respected everyone he encountered. Arvīds and Mariss both suffered from heart trouble, the father collapsing on the podium, the son very nearly following suit. Marris died in 2019 at home in St Petersburg.

Mahler: Symphony No. 7 in E Minor – II. Nachtmusik: Allegro moderato (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; Mariss Jansons, cond.)

The Järvi family

Neeme and Paavo Järvi: Estonian-American Conductor Neeme, at age 83, is still a busy international figure. He studied percussion and conducting at the Tallinn Music School, and made his debut at 18, quite a young age for conductors. Beginning his career in his native country, he was music director of the Estonian Radio and Television Orchestra, the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra, chief conductor of the Opera House Estonia and the Estonian State Symphony, and he lead the very first performances of Strauss’ Der Rosenkavelier and Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess in the USSR. The premiere of Credo, Arvo Pärt’s deeply religious work, earned Järvi the disfavor of the Communist government, which compelled him to leave Europe.

Almost immediately, orchestras all over the globe sought him out—the Boston, Philadelphia, and New York Philharmonic orchestras, and he received appointments to the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the Japan Philharmonic, the Royal Scottish Orchestra, the Gothenburg Symphony in Sweden, and the Detroit Symphony. When he guest-conducted the Minnesota Orchestra, I enjoyed his characteristic wit, his ease on the podium, and his varied programming, often introducing us to works we’d never played! His massive discography of both known and rare works is mind-boggling—well over 450 recordings. Stick-wielding, as he calls it, must include all of the music out there. He prides himself in helping composers by doing justice to their works, even if they are not the so-called “masterpieces.”

Paavo Järvi considers himself fortunate that there are several conductors in his family. He’s been privy to “insider” information, about repertoire, about the stumbling blocks, about how to build relationships with orchestras. His positions include Chief Conductor of such esteemed ensembles as the Tonhalle Orchester-Zurich, the NHK Symphony of Tokyo, and he is Artistic Director of Die Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, and the Estonian Festival Orchestra, a group he founded. Each season in Pärnu, father and son hold master classes, conduct performances, and tour with the Festival orchestra.

The conductor laureate of several ensembles including the Cincinnati Symphony and Orchestre de Paris, the Grammy-Award-winning maestro is in demand as guest conductor of some of the greatest orchestras in the world. Paavo does not see the role of the conductor as autocrat. He thinks of himself more as a teacher and collaborator. The conductor, he feels, must have a terrific technique to be able to communicate through gestures, and to build a collective interpretation with the musicians. Listen to his illuminating interview below. I can say, also from experience, that working with him was a pleasure.

Paavo’s two siblings are also outstanding musicians—Kristjan is a conductor (how did you guess?) and Maarika was principal flute of Madrid’s RTVE Orchestra.

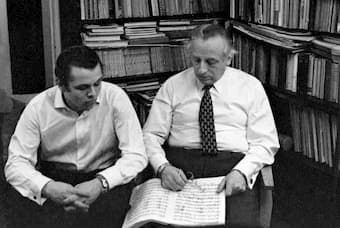

Kurt and Ken-David Masur

Kurt and Ken-David Masur: Distinguished maestro Kurt Masur, who passed away in 2015, is widely recognized for rebuilding the New York Philharmonic during his tenure (1991-2002) as music director. Previously the long-time conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra, one of the world’s first-class orchestras, he was chiefly known for his demanding and intense style and for his masterful interpretations of German and Austrian music, such as the works of Beethoven, Brahms, and Bruckner. Nonetheless, during his time with the New York Philharmonic, he oversaw 40 commissions, of composers Tan Dun, Ned Rorem, Kaija Saariaho and others, and he conducted premieres of Hans Werner Henze’s Ninth Symphony and music of Sofia Gubaiudulina.

Despite the fact his father wanted him to be an electrician, Kurt studied the piano, organ, cello, and percussion. When he sustained a tendon injury at age 14, Kurt turned to conducting. Due to the ethical, moral, and human dimensions he brought to the music-making, his tenure with the NY Philharmonic, is now deemed the orchestra’s golden years. Masur gave his support during the fall of the Berlin Wall, and after 9/11 he led a performance of Brahms’ German Requiem, which was nationally televised. When Masur left the orchestra, he was named their first music director emeritus. Subsequently, he took on the role of Music Director of the Orchestra National de France, the London Philharmonic, and he was also the honorary guest conductor of the Israeli Philharmonic. The New York Philharmonic has established the “Kurt Masur Fund for the Orchestra”, which finances a young conductor’s debut each season with the orchestra.

R. Strauss: Ein Heldenleben (A Hero’s Life), Op. 40, TrV 190 – Der Held (The Hero) (Richard Strauss 150th Anniversary “Ein Heldenleben” Orchestra; Ken-David Masur, cond.)

Ken-David Masur was born in Leipzig. He began piano lessons at age 6 and he sang in the Gewandhaus children’s chorus as a boy soprano. His affinity for singing led him to a formal vocal education. When his father came to this country, Ken-David continued his music studies at Columbia University. During his youth, he was certain he didn’t want to be a conductor in the shadow of his famous father. But an opportunity at Columbia fell into his lap. It was exciting to conduct Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas. Only after Kurt quietly approved, did Ken-David start making a name for himself, becoming principal guest conductor of the Munich Symphony, and resident conductor of the San Antonio Symphony. His Boston Symphony debut at Tanglewood in 2012, a performance where father and son shared the program, was not nepotism, but due to the fact that Kurt suffered from Parkinson’s and had become too frail to lead an entire program. Impressed by Ken-David, the Boston Symphony appointed him assistant conductor. Recently, Ken-David became music director of the Milwaukee Symphony beginning with the 2019-20 season.

There are several more father and son conducting dynasties. We will explore them in the next article.