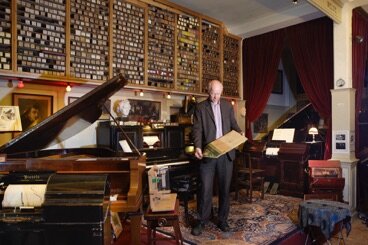

A few days ago, we were invited to an historic home on a nearby lake, a rambling manor that had been in one family for generations. Inside we encountered sensory overload—antiques, and collectibles, decades-old toys, hundreds of books, silver sets, beer mugs, games, stained glass, china, and musical instruments. In the center of the room sits a player piano. My host showed me how it works, as I had never seen the mechanism up close. He dug through boxes of piano rolls and came up with a gem—George Gershwin playing his Rhapsody in Blue. My host put in the roll, set the tempo, and off it went. I sat at the keyboard mesmerized by the electrifying playing. I felt as if I was in the presence of the master!

Player piano

Once we returned home I quickly did some research and discovered there is a Pianola Museum in Amsterdam. I learned that many distinguished artists produced piano rolls.

Owning a piano implied you had attained a certain stature in society in the 19th century. Refined, well-bred women were expected to play the instrument, but not everyone could master the art of piano-playing. The dearth of good teachers and endless hours of daily practice discouraged more than a few young ladies. A piano that could play itself, and entertain guests seemed like the perfect answer, though a bit far-fetched.

The first ‘piano players’ appeared in the 1890s and were on wheels. “You rolled it up to your piano keyboard, adjusted several knobs for height, then sat in front of it (some distance by now from the piano itself) and pumped two treadles that worked its pneumatic insides. A traveling perforated paper roll from forty-four to sixty-five notes’ compass actuated felt-tipped wooden rods that dropped down on the piano keys and played them.”

The French and Italians attempted their own versions as early as 1874, but not until Edwin S. Votey developed a pneumatic piano player, which was available by 1898, did the instrument capture the imaginations of the general public. By 1914 several companies vied to produce the popular piano player, which outsold regular pianos. The manufacturers realized that building the mechanism into the piano would make much more sense (and money.) The instruments became so popular, and gaudy, that every saloon had to have one, and all types of music—ragtime, film music, and Sousa marches—were produced by the mechanical perforating device.

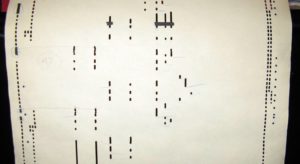

Roll innards

Meanwhile, the well-known German company Freiburg, M. Weite & Söhn, took the piano player in another direction—the rolls made by the painstaking transcription from actual performances of the greatest artists of the day. It was a complex process, which offered more dynamic variety, rubato, and even the touch and shadings of the particular player, and he or she could edit the performance before it was finalized.

The Welte-Mignon, as it was called, became the first self-playing piano utilizing rolls performed by these artists. By 1913, in America, the Aeolian company, in a partnership with Steinway, released their version of a reproducing piano—the Duo-Art, which could create a remarkably authentic duplicate of the artist’s performance.

The excitement was palpable. The piano could now be heard everywhere, including in people’s homes. Music critic Ernest Newman, “listened to a performance in London in which passages of a Liszt rhapsody were played on a Duo-Art in Aeolian Hall, alternately by a pianist and by a roll he’d made. ‘With one’s eyes closed,’ Newman remarked afterward, ‘it was impossible to say which was which.’

Duo-Art original roll showing hand-punched accents

Those who made piano rolls in the 20th century and preserved their artistry, reads like a who’s who of notable music figures—composers Debussy, Prokofiev, Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, the 80-year-old Saint-Saëns, even Mahler; pianists, Josef Hofmann, Myra Hess, and Alfred Cortot; jazz and popular artists, such as Fats Waller, Liberace, and Scott Joplin.

And over 100 composers wrote music for the instrument. Stravinsky rewrote many of his works for pianola, such as the Firebird, Petrushka, The Rite of Spring, Song of the Nightingale, and Pulcinella, and when he began work on the ballet Les Noces he worked with the Aeolian company to perforate an accompaniment to his score. Subsequently, in 1917, Stravinsky wrote Etude for Pianola, premiered by Reginald Reynolds in 1921 at London’s Aeolian Hall.

Eventually with the advent of the radio and improved recordings, the player piano died out. Nonetheless rolls continue to be made today and companies have specialized in restoring player pianos.

Player pianos became stunning works of art inside and out. Juan Sánchez, a pianist and composer sent me a photo of the Farrand-Cecilian Craftsman Style Player Piano made of beautiful quarter sawn oak with hammered copper hinges, pedals, and hardware. Two authentic Gustav Stickley hammered-glass lamps adorn either side of the keyboard. One of Votey’s earliest instruments is in the collection at The Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C. and more information can be had at the Pianola Institute’s website.

What a privilege to gain insight into performances of 100 years ago, before CD’s, recordings, tapes, and wax cylinders. These high-quality recordings teach us about the historic fashion, performance practices, and the style, and techniques of the day. I marveled at the long sheet of paper with hole punches and frayed edges, rolling by, the dots connecting, the piano keys bouncing up and down as if by magic, and I loved every second of it.

I have three dual art piano rolls how do I find the value of them