As soon as you start trading wildlife for food, scary things can, and will happen. The newest virus capturing the world’s attention is a bug belonging to the coronavirus family that originated in a live-animal market in Wuhan, in Hubei Province, China. Bats, civets, porcupines, turtles, bamboo rats, many kinds of birds and other exotic animals are piled together and readily sold for home and restaurant cooking. Many of these exotic species harbor unknown viruses, and always looking for new hosts, they easily pass to other creatures, which occasionally includes you and me. It gets truly scary when the mutated virus gains the ability of human-to-human transmission, as the mobile world including a pandemic is merely a flight or two away. It is now believed that Coronavirus nCoV-2019 originated with bats. Bats have never had the best reputation, and while they do provide some benefits to humans, they are natural reservoirs of many pathogens. As such, many cultures associate bats with witchcraft, malevolence, vampires, and even death. Given such notoriety, it’s only natural that they turn up in literature and music as well. The Norwegian composer Harald Lie (1902-1942), who died of tuberculosis at a young age, composed a stunning orchestral song entitled “A Bat’s Letter,” based on poetry by Aslaug Vaa.

As soon as you start trading wildlife for food, scary things can, and will happen. The newest virus capturing the world’s attention is a bug belonging to the coronavirus family that originated in a live-animal market in Wuhan, in Hubei Province, China. Bats, civets, porcupines, turtles, bamboo rats, many kinds of birds and other exotic animals are piled together and readily sold for home and restaurant cooking. Many of these exotic species harbor unknown viruses, and always looking for new hosts, they easily pass to other creatures, which occasionally includes you and me. It gets truly scary when the mutated virus gains the ability of human-to-human transmission, as the mobile world including a pandemic is merely a flight or two away. It is now believed that Coronavirus nCoV-2019 originated with bats. Bats have never had the best reputation, and while they do provide some benefits to humans, they are natural reservoirs of many pathogens. As such, many cultures associate bats with witchcraft, malevolence, vampires, and even death. Given such notoriety, it’s only natural that they turn up in literature and music as well. The Norwegian composer Harald Lie (1902-1942), who died of tuberculosis at a young age, composed a stunning orchestral song entitled “A Bat’s Letter,” based on poetry by Aslaug Vaa.

Harald Lie: A Bat’s Letter, Op. 6 (Anne-Lise Berntsen, soprano; Norwegian Radio Orchestra; Ari Rasilainen, cond.)

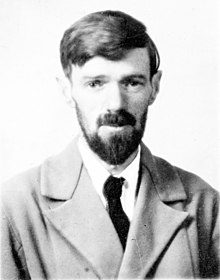

David Herbert Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (1885-1930) wasn’t shy about exploring issues such as sexuality, emotional health, spontaneity, and instinct. High on his list were reflections dealing with the dehumanizing effects of modernity and industrialization. According to literary critics, Lawrence didn’t particularly like bats but that didn’t stop him from writing about them in his poetry. In essence, “he constructs a dummy creature with a mask-like face which parodies and subverts the very notion of an essential batness.” In the long and amusing poem “Man and Bat” he has a bat fly round and round in mad circles. Encoding his own experience, Lawrence demonstrates how the every day might be transfigured into art and given poetic expression, and how writing is “inseparable from a process of becoming.” In the hands of composer Howard Skempton Man and Bat becomes a dramatic and lively conflict ending in an act of compassion.

Howard Skempton: Man and Bat (Roderick Williams, baritone; Ensemble 360)

Batman over the years

Contrary to the world of poetry, popular culture has embraced the bat in the shape of the comic superhero Batman. In the United States at least, Batman has turned out to be one of the most enduring superhero figures. His existence started in the metropolis Gotham City, where he still battles the most evil and brilliant criminals. He was only eight years when he persuades his parents to leave an opera performance before it is over. Outside in an ally, his parents are shot and killed by a criminal while the boy watches. At that point he decides that all criminals must be punished. Batman’s worst enemies are the Joker, Two-Face and the Penguin, all psychopathic adversaries with deliciously sadistic inventiveness. While you might possibly have seen some of the more recent cinematographic efforts, you might not know that the Danish composer Niels Marthinsen (b. 1963) has written a Concerto for 3 Trombones subtitled “In the Shadow of the Bat.” The work opens with the creation of Batman, and is followed by a “Villainous Fugue” featuring all three already mentioned villains. For Marthinsen, “Pop culture can renew classical music. Not by banalizing art to pop, but by acknowledging the cultural references of people of our time.”

Niels Marthinsen: Concerto for 3 Trombones, “In the Shadow of the Bat” (Hakan Bjorkman, trombone; Stefan Schulz, trombone; Jörgen van Rijen, trombone; Aarhus Symphony Orchestra; Christian Lindberg, cond.)

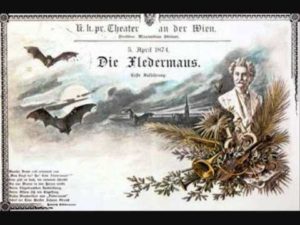

Strauss’ Die Fledermaus

And how about this for a famous Bat story? Gabriel von Eisenstein is due to report to prison, having defaulted on his taxes. Before he heads for jail, he is invited by his friend Dr. Falke to attend a fancy-dress part at the home of Prince Orlofsky. Falke is actually plotting revenge, having been abandoned drunk and dressed like a bat at an early costume party. Eisenstein’s wife Rosalinde takes advantage of her husband’s absence to meet with her former lover Alfred, who is mistaken for her husband and taken to prison. Eisenstein’s maid Adele has secretly borrowed a dress pretending to be an actress, and Rosalinde also appears disguised as a Hungarian countess. Mistaken identities abound, and Eisenstein flirts with his own wife. In the meantime, the prison warden Frosch is unhappy with Alfred’s singing, and the confusion continues once the real Eisenstein arrives. He immediately suspects his wife, and disguised as the lawyer Dr. Bling, he cross-examines Rosalinde and Alfred. Rosalinde retaliates by revealing his identity by producing Eisenstein’s watch, which the supposed Hungarian countess had received from him at Prince Orlofsky. Falke admits his part in the plot and all ends in apparent satisfaction. In brief, that’s the story that provides the foundation for Johann Strauss II’s operetta “Die Fledermaus”. And in his “Fledermaus Paraphrase” of 1912, Leopold Godowsky provides “the last word in terpsichorean counterpoint.” You can certainly hear the sparkling champagne everywhere, or was it the fluttering of the bat?