Le Dome café, Paris, in the 1920s, central to these books.

Homer Evans makes his first appearance in The Mysterious Mickey Finn (1939), Hugger-Mugger in the Louvre (1940), Mayhem in B-Flat (1940), all of which are set in Paris in the years between the wars. Later books in the series take him to the US. As you can tell from the titles, these are parodies of the detective novel as much as they are contributions to the genre.

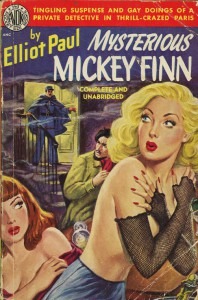

The Mysterious Mickey Finn

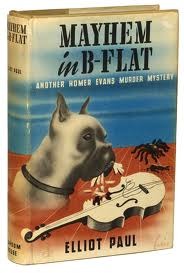

Mayhem in B-flat

The story closes with an escape from a lunatic asylum, with the noise described as something of “Wagnerian proportions, with Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps thrown in.”

In the third book, Mayhem in B-Flat, there’s a stolen Guarneri violin, owned by Andrew Flood (aka Anton Diluvio), and a concert with an unbelievable programme:

Sonata for Violin and Piano, op. 13 | Sauvequipeut |

Variations on an Air by Monteverdi | Vivaldi |

Concerto Serioso | Tienemiedo |

Elegie plus or moins in Ut | Philidor |

–Intermission– |

|

Narcissus | Nevin- Diluvio |

Star of the Sea | Old American |

Prelude in C sharp Minor, arr. for solo violin | Rachmaninov – Diluvio |

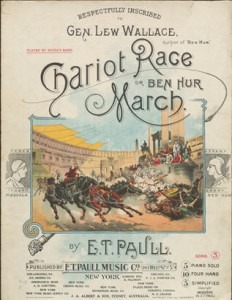

Course au Chariot de Ben Hur | Paull – Diluvio |

Cover of Edward Taylor Paull’s Chariot Race or Ben Hur March

Some of these are known works, others are delightful inventions. The composer Sauvequipeut’s name means “Every Man for Himself” but both Fauré and Grieg wrote Opus 13 Violin Sonatas. As many works as Vivaldi did write, a Variation on an Air by Monteverdi wasn’t one of them. Tienemiedo means “to be scared,” in Spanish. The French composer Philidor (1726 – 1795) wouldn’t have written a title as modern as “Elegie More or Less in C.” That sounds more like Satie.

For the second half of the concert, Ethelbert Nevin did write a piece called Narcissus, which is one of his best-loved pieces and is part of his Opus 13 Water Pieces. Star of the Sea is a translation of one of the names for the Virgin Mary, Stella Maris, but is not an old American song. Rachmaninov’s Prelude in C sharp minor doesn’t appear to exist in an arrangement for solo violin, and the last work, by E.T. Paull, is another piano work but is more famous for its cover than its contents.

Paull: Chariot Race, “Ben Hur March”

There are some wonderful asides, such as one about the critics and their grumblings about the concert: “The first part contained several little-known selections from the music of past age, which would necessitate the critics writing something out of their heads instead of looking what they had last said…. And the second half consisted principally of popular tunes which those blasé gentlemen could not contemplate without loathing.”

Elliot Paul knew enough of the musical world to pull its leg and, as musical readers, we can appreciate his humor.