Alexandre Tansman

The idea of using jazz idioms in an otherwise “serious” composition was a recurrent element in European music between the two World Wars. Composers of all nationalities sought to break down the distinction between high and popular art, and the blues became a favorite vehicle. Rooted in African American folk forms, the blues arose in the Southern United States and became internationally popular in the 20th century. Various types of vocal folk music merged into a type of folk song having the formal and stylistic traits that characterize the blues: strophic variations on a simple harmonic pattern, texts that deal with melancholy and hardship, and a highly expressive vocal style. Although the content and definitions of blues have changed to fit shifts in musical fashions, technologies, performance styles, and audiences, the blues has maintained its own identity and evolutionary history. And while it is regarded as the foundation for nearly all later American popular forms, it’s impact on the European music scene cannot be emphasized strongly enough. Alexandre Tansman (1897-1986) hailed from Poland but spent most of his life in France. He spoke seven languages, traveled extensively, and was celebrated as “one of the leading composers of his time.” Tansman’s music features a particular light charm intertwined with tenderness and melancholy, and his blues compositions disclose his abiding love of lyricism.

Alexandre Tansman: 3 Preludes en forme de Blues (Iva Vaglenova, piano)

Aaron Copland in Paris

Eager to seek out the newest European musical styles, the emerging American composer Aaron Copland (1900-1990) travelled to Paris to first study with the famed pianist Isidor Philipp. However, for instruction in composition he soon consulted the legendary Nadia Boulanger. Initially, Copland had reservations about “studying with a woman,” but he soon found her instruction much to his liking. “This intellectual Amazon,” he writes, “is not only familiar with all music from Bach to Stravinsky but is prepared for anything worse in the way of dissonance.” In deep gratitude to his teacher, Copland later wrote, “I shall count our meeting the most important of my musical life. Whatever I have accomplished is intimately associated in my mind with those early years, and with what you have since been as inspiration and example.” In Paris, Copland became highly interested in jazz idioms, a fascination and inspiration that would stay with him throughout his career.

Aaron Copland: 4 Piano Blues (Robert Silverman, piano)

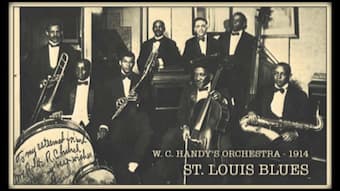

William Christopher Handy, 1914

In his autobiography, William Christopher Handy (1873-1958) referred to himself as the “Father of the Blues.” One of the most influential songwriters in the United States, Handy did not actually create the blues genre, but he took the blues from a regional musical style with a limited audience to a new level of popularity in urban centers. Through his publishing efforts, Handy sparked a jazz craze that saw over four hundred songs published that had “blues” in their titles within a couple of years.

Ravel in New York

The first article on jazz as a musical style was published in the Chicago Tribune in 1915 and titled “Blues Is Jazz and Jazz is Blues.” Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) quickly found inspiration in this popular American idiom as it was sweeping Paris in the 1920s. In due course, Ravel embarked on a 4-month tour of North America. In all, he visited 25 cities coast-to-coast, and performed and conducted the leading orchestras of Canada and the Unites States. Ravel also made tourist visits to Niagara Falls and the Grand Canyon, and he was fascinated by the dynamism of American life. He admired “the huge cities, skyscrapers, and its advanced technology, and was impressed by its jazz, Negro spirituals, and the excellence of American orchestras.” American cuisine was apparently a different matter altogether. His fascination with various jazz elements and forms emerges in a number of his composition, including the second movement his Violin Sonata No. 2 labeled “Blues.”

Maurice Ravel: Violin Sonata in G Major, “II: Blues” (Philippe Graffin, violin; Claire Désert, piano)

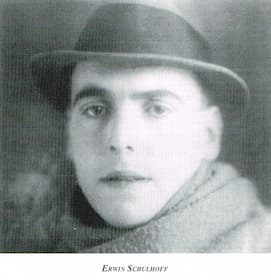

Erwin Schulhoff

Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) was a child prodigy who won the Mendelssohn Prize for piano and for composition in 1918. Drafted into the Austrian army, Schulhoff served for the duration of WW1, and the horrors of war caused a breakdown of all the values he had previously believed in. Returning home from the war he became a convinced socialist, and he began searching for a musical solution that would liberate him from his previous post-Romantic aesthetic. He initiated a series of concerts of atonal music, and he became acquainted with the Berlin Dadaists, particularly the painter George Grosz. Grosz was among the first collectors of gramophone recordings of contemporary American jazz, and for Schulhoff it became a compositional path to extricate European postwar music from its crisis. In his compositions, Schulhoff stretched the definition of jazz considerably by not drawing a definite line between jazz and popular entertainment culture of European origin. But he clearly understood that the jazz idiom was contemporary while remaining accessible to a broader audience.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Erwin Schulhoff: 5 Études de jazz (Charleston, Blues, Chanson, Tango, Shimmy) (Eldar Nebolsin, piano)