Joseph Marx

Joseph Marx (1882-1964) enjoyed an esteemed reputation as a major composer and teacher. Nikolay Medtner, one of the most important representatives of the group of composers based in Moscow that included Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Scriabin and Alexander Taneyev expressed his admiration for Marx in a letter of 1949. “It was an unexpected blessing to meet you—it was a sign that everything unexpected, marvelous and eternally romantic is still present among us, despite all the best efforts of the artistic world’s current movers and shakers to stamp it out.” Marx had a particularly low opinion of 20th-century experimentations, and in his criticisms and essays never even mentions Schoenberg, Berg or Hindemith. As a composer, he was deeply fascinated by Debussy, Scriabin and Reger, and he never made any secret of his profound admiration for the Classical giants of music. His Partita in modo antico pays tribute to the old masters of vocal polyphony combining church modes with linear counterpoint in a basic suite organization.

Joseph Marx: Partita in modo antico (Bochum Symphony Orchestra; Steven Sloane, cond.)

Alfredo Casella

Although Alfredo Casella (1883-1947) was born in Turin, he spent his formative years in Paris. By all accounts, he had a voracious musical curiosity and “his early influences from his teacher Fauré, his friend Enescu and his youthful idol Mahler were overtaken around the First World War by affinities with Bartók, Debussy, Schoenberg and above all Stravinsky.”

1910 letter from Mahler to Casella

Once he had returned to Italy, he made a springtime trip to Tuscany. “This region I barely knew,” he writes, “left a profound impression on me. Not only because of its art with which, obviously, I was well acquainted, but above all through its wonderful scenery. I now understood that an Italian can never be an impressionist, and that the transparent clarity of the Tuscan landscape is the same as that of our art.” The classical transparency he experienced in Tuscany informed his compositional language, and his Partita for piano and small orchestra, composed in 1924/25, emerged from this period of “profound reflection.” Casella pays homage to the Italian Baroque instrumental ancestry, and the Partita, according to the composer, “was for many years the most-performed modern piece for piano and orchestra.”

Alfredo Casella: Partita, Op. 42 (Sun Hee You, piano; Rome Symphony Orchestra; Francesco La Vecchia, cond.)

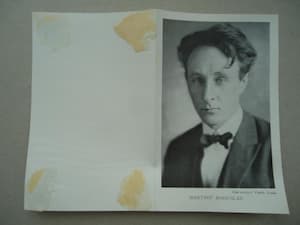

Bohuslav Martinů in Paris

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) was never entirely comfortable in the highly conservative musical environment of Prague. He left for Paris in 1923 and quickly assimilated a substantial variety of musical styles, drawing inspiration from sources ranging from Renaissance music to Jazz. As a result, his personal style was rich in “color without ever losing its unmistakable identity.” Although it is impossible to reduce his compositions to any particular musical style, the composer apparently had a close affinity to chamber music.

Bohuslav Martinů

The early 1930s were a particularly creative period in Martinů’s life, and he composed his Partita in 1931. Martinů revisits this Baroque genre by composing a series of dance movement. Simultaneously, Martinů designates the work as “Suite No. 1,” as it also shares its orientation with some pre-classical models. “The Partita forms a sequence of (virtual) dance movements, balanced by a highly refined tonal language that demands a virtuoso display from the entire orchestra. Its thematic material is derived from and modeled after traditional folk music, which Martinů develops in a modernist style.”

Bohuslav Martinů: Partita, H. 212 “Suite No. 1” (Ingolstadt Georgian Chamber Orchestra; Ruben Gazarian, cond.)

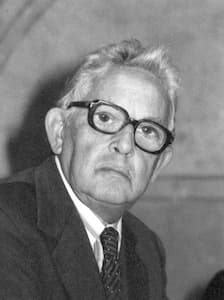

Goffredo Petrassi

Goffredo Petrassi (1904-2003) is considered the “most significant Italian composer of the mid-20th century.” Born in the Roman countryside, Petrassi became a chorister at the Schola Cantorum and received the “musical education that Palestrina and many other musicians had centuries before.” He taught himself to play the piano and studied at the Conservatorio di Santa Cecilia. While still in his twenties, he won two national music prizes with his Partita for orchestra as he attempted to create a national Italian revival in classical music. Concurrently, he was greatly influenced by the neoclassical styles of Bartók, Hindemith and Stravinsky. Various models and influences converge in his Partita for Piano dating from 1926. The use of dance forms is filtered through the chords of Ravel, the unexpected harmonies of Debussy and the abstraction of Hindemith counterpoint.

Goffredo Petrassi: Partita for Piano (Pietro Massa, piano)

Sigurd Raschèr

Sigurd Raschèr (1907-2001) was the son of an American military physician temporarily stationed in Germany. He studied piano and clarinet, and when the Berlin Philharmonic needed a saxophonist for a performance in 1930, Raschèr discovered his true calling. He made his American debut with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky in 1939, and he became a hugely important figure in the development of the 20th century repertoire for the classical saxophone. In all, 208 works for saxophone are dedicated to him, “and it is not without significance that among all the pieces written for and dedicated to him during his life, not one was commissioned. He inspired new music, he never needed to purchase it.” Among these dedicated compositions is a delightful Partita for alto saxophone and piano by Erwin Dressel (1909-1972). He became acquainted with Raschèr in the 1930s and began a series of dedicated compositions, including a Sonata and a Concerto. The Partita dates from 1964, and it unmistakably sounds the deeply voiced harmonies and arching melodies previously favoured by Johannes Brahms.

Erwin Dressel: Partita for Alto Saxophone and Piano (Ronald L. Caravan, alto saxophone; Sar Shalom Strong, piano)

Kenneth Leighton

The British composer and pianist Kenneth Leighton (1929-1988) came to the attention of Gerald Finzi, who introduced him to Vaughan Williams. In turn, Leopold Stokowski premiered his overture “Primavera Romana” in Liverpool in 1951. In the same year he was awarded a Mendelssohn Scholarship, which enabled him to study with Goffredo Petrassi in Rome. Upon his return to England, he held various appointments at the Universities of Leeds, Oxford and Edinburgh. His Partita for cello and piano, Op. 35 was completed in 1959 and already demonstrates his mature musical language. The composer himself gave the following description of the work, “The opening Elegy is an intense lyrical movement with two distinct themes and a final mysterious section in the manner of a slow march. This is followed by a brilliant and energetic Scherzo […] while the final movement, Theme and Variations, is more extended and carries the main emotional weight of the work. A bell-like theme […] is followed by variations which bear the titles – Allegro inquieto, Ostinato (a kind of Passacaglia), March, Appassionato, Waltz, and finally Chorale.”

Kenneth Leighton: Partita for cello and piano, Op. 35 (Raphael Wallfisch, cello; Raphael Terroni, piano)

Krzystof Penderecki

Krzystof Penderecki (1933-2020) considered music a fundamental and essential part of the human condition. As an artist, he went on a never-ending quest for self-expression. Possibly the most versatile, multi-faceted and stylistically diverse composers of modern times, Penderecki experimented with serialism, tonality, non-traditional means of expression and new techniques before settling on a Post-Romantic idiom. Penderecki had spent decades searching for and discovering new sounds. At a musical and personal crossroads, the composer “had to go and find other ways of writing music.” That new style evolved from his “studies of the forms, styles and harmonies of past eras.” He returned to Gregorian chant and sixteenth-century polyphonic conventions and created a synthesis of his lifelong devotion to music and to his devout spirituality. His Partita, composed in 1971, has notable roles for electric and bass guitars, harp and double bass. As the title implies, it references a musical style and genre that is securely located in the past. It is an exciting fusion of ancient and modern, “with a musical vocabulary that is patently modern, yet is animated by a spirit that is both ancient and timeless.”

Krzysztof Penderecki: Partita (Elzbieta Stefańska, harpsichord; Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra; Antoni Wit, cond.)

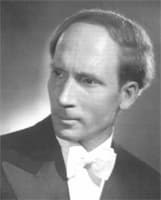

The young Arvo Pärt

Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) found his compositional voice by employing serial techniques. Sufficed to say, he was immediately at odds with the aesthetic ideals of the Soviet Union. Tikhon Khrennikov, the leader of the Union of Soviet Composers, officially renounced him as belonging to an “exclusive small group of composers existing in the backwater of the broad stream of musical life and engaged in formal searching and fruitless experimentation…These compositions make it quite clear that the twelve-tone experiment is untenable: ultra-expressionistic, purely naturalistic depiction of the state of fear, terror, despair and dejection.” Pärt ignored the official reprimand and continued to apply serial procedures throughout the 1960’s. However, his compositions gradually also became influenced by his interest in J. S. Bach. Serial techniques and his interest in Bach emerge forcefully in his Partita, Op. 2, dating from 1959. Uncompromising and atonally rambling, “all the seeds of his later musical language, including a general economy of material with an omnipresent focus on melody, are already firmly present.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arvo Pärt: Partita, Op. 2