Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme

Credit: www.staragora.com

Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (Der Burger als Edelmann) Suite, Op. 60, TrV 228c

The original Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme— a play with dance, singing, and music composed by Jean Baptiste Lully, was performed for the court of Louis XIV. The piece is a satire decrying the vanity of aristocrats and the pretentiousness of the middle class. The title meaning “middle class aristocrat” is sarcastic— an oxymoron. In Molière’s time only someone of noble birth could be an aristocrat.

The nine parts of the work tell an amusing story. Monsieur Jourdain, our main character, vows to be accepted as an aristocrat. He orders splendid new clothes and tries to learn fencing, dancing, music making and philosophy— all the gentlemanly arts—but he only succeeds in making a fool of himself.

The chamber piece is a stunning tour-de–force for the concertmaster, principal cello, trumpet, piano, and oboe. Each instrument is featured in the several movement work.

The overture begins with bustling preparation for a feast hosted by Monsieur Jourdain in his house in Paris. As the chaos in the kitchen becomes frenzied, the music gets faster and faster—and tough to play, I should add. A beautiful oboe line interrupts. The dancing master enters, characterized by the utterly charming and disarming Menuett. Then the fencing master appears. They both struggle to teach our protagonist, but to no avail. Their ungainly pupil M. Jourdain has two left feet. The swashbuckling swordsmanship and the lumbering feet of Jourdain are evident in the fencing movement.

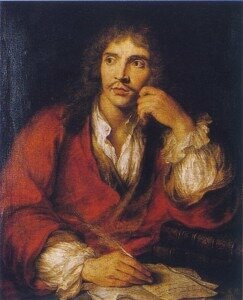

Molière

Credit: fr.wikipedia.org

Strauss honors other composers in the work and he quotes from his own music too. The hushed Menuett after Lully is a gentle almost hymn-like tribute to the composer. There are ravishing allusions to Strauss’ opera Der Rosenkavelier and quotes from Don Quixote, his tone poem for solo cello. The horn players bray like sheep, just as they do in Don Quixote, preceding the Intermezzo—a cello solo movement. This movement reveals everything expected of a cellist— a gorgeous sound, a heartfelt interpretation and a brilliant technique. Strauss certainly favored the golden tones of the cello. Strauss here writes a gentle accompaniment of one harp and a second solo cello to enrich but never cover the solo cello. Toward the end of the movement there is a long sigh in the cello and the sheep return, as do the cackling flute, oboe and piccolo.

This wonderful solo with its challenges is certainly why the movement is frequently required for principal cello orchestral auditions. I remember preparing this movement for my audition in Minnesota. Like other cello solos that Strauss wrote, it drifts up and up into the stratosphere on the highest string. Don’t try this if you have a fear of heights! To this day, it is one of my favorite cello solos ever and I loved to perform it later in my career—

after the audition, that is.

Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme requires close collaboration with the other players, especially the concertmaster. There are several places where there are duets between the cello and violin, cello and horn, and other instruments. Listen also for fancy finger work from the trumpet and piano.

The piece ends with the hectic bustle of the dinner being served. We can hear quotes from works of Meyerbeer, Wagner, and even Verdi all topped off when a serving boy leaps out to dance a Viennese waltz.

Other artists have been inspired by this charming music including George Balanchine, who choreographed a version of Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme for the New York City Opera in 1979 starring Rudolf Nureyev.

Like all of Strauss’ music, it is extremely difficult to perform well. One feels especially exposed, as this is such a small group of players. But it is a gorgeous work and if you’ve never heard this piece I am delighted to be able to introduce it to you!