| Canción de Jinete Córdoba Lejana y sola. Jaca negra, luna grande, Por el llano, por el viento Córdoba. | The Horseman’s Song Córdoba Distant and lonely. Black steed, big moon, Across the plain, through the wind Córdoba. |

In this poem ‘Canción de Jinete’ (from Lorca’s Canciones) García Lorca uses an ancient Hispano-Arab form of poetry, wonderfully musical in its repetition and sound, where the real meaning of the poem is obscured. Who is this rider, what does his destiny hold for him, and why does death await him before reaching Córdoba? The Moorish poets of the Middle Ages used similar forms of allusion and repetition. The ‘Ay’ in García Lorca’s poem recalls the Flamenco tradition of the ‘cante jondo’, the profoundly musical tradition of Andalusia, which García Lorca and Mañuel de Falla started to revive in 1922.

Manuel de Falla: Noches en los jardines de Espana (Nights in the Gardens of Spain) (1915)

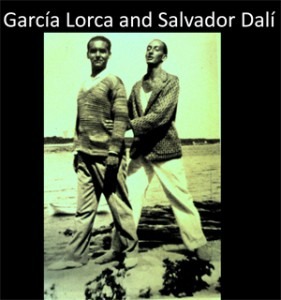

A true Andalusian, García Lorca was born in 1878 in Fuente Vaqueros near Granada. He was taught, initially as a classical pianist, by his mother, a teacher and gifted pianist, and only later in his youth turned to poetry and theatre. His first written works carry the titles of musical compositions, such as “Nocturne”, “Ballade” and “Sonata”, reminiscent of Chopin and Debussy, whom he admired. At the famous Oxbridge-inspired ‘Residencia de Estudiantes’ in Madrid, where García Lorca studied from 1919 onward, he met and befriended Manuel de Falla, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel and many other young artists, musicians and writers of his time. Juan Ramon Jimenez, one of the greatest Spanish poets of the so-called 1898 generation (others include Antonío Machado and Miguel de Unamuno) took him under his wing.

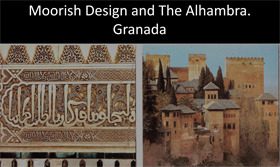

García Lorca published his first collections of poems in 1921, followed by ‘Canciones’ and ‘Romancero Gitano’. His poems express, as he says “… carved altar pieces of Andalusia with gypsies, horses, archangels, planets, its Jewish and Roman breezes, rivers, crimes, the everyday touch of the smuggler and the celestial note of the naked children of Córdoba … a book that hardly expresses visible Andalusia at all, but where the hidden Andalusia trembles”. Their musicality is reminiscent of the Hispano-Arabic tradition of poetry of the Middle Ages (see our previous article for Interlude). The poem above, as well much of his oeuvre including his plays, Yerma and the Blood Wedding, which he considered written as a “trilogy of the Spanish earth” although never completed (García Lorca was shot by Franco’s forces in 1936 in the beginning of the Spanish Civil War), should be seen in reference to the Moorish tradition of poetry, song and architecture.

García Lorca published his first collections of poems in 1921, followed by ‘Canciones’ and ‘Romancero Gitano’. His poems express, as he says “… carved altar pieces of Andalusia with gypsies, horses, archangels, planets, its Jewish and Roman breezes, rivers, crimes, the everyday touch of the smuggler and the celestial note of the naked children of Córdoba … a book that hardly expresses visible Andalusia at all, but where the hidden Andalusia trembles”. Their musicality is reminiscent of the Hispano-Arabic tradition of poetry of the Middle Ages (see our previous article for Interlude). The poem above, as well much of his oeuvre including his plays, Yerma and the Blood Wedding, which he considered written as a “trilogy of the Spanish earth” although never completed (García Lorca was shot by Franco’s forces in 1936 in the beginning of the Spanish Civil War), should be seen in reference to the Moorish tradition of poetry, song and architecture.

Manuel de Falla: Noches en los jardines de Espana (Nights in the Gardens of Spain) (1915)

Manuel de Falla: Noches en los jardines de Espana (Nights in the Gardens of Spain) (1915)

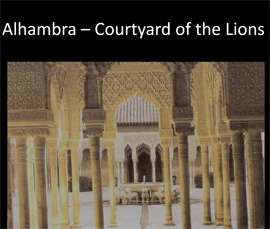

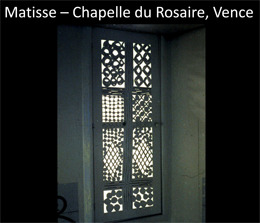

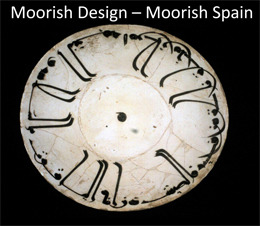

In Moorish architecture and art, as discussed in my previous article on the Alhambra in Granada, there is also never a direct way into the various courtyards … the path to the most important dwellings is always obscured and circuitous. Moorish design emphasizes nature, the garden of paradise, but within the volutes and arabesques are hidden poems and inscriptions from the Koran – nothing is direct, everything is circuitous, allusions and metaphors hide ‘reality’, just as the louvered doors of the harems hide their inhabitants – the women can see, but cannot be seen. With his poems and plays, García Lorca brings these concepts into the 20th century, just as Matisse would use them in his architectural designs of the Chapelle du Rosaire in Venice, France.

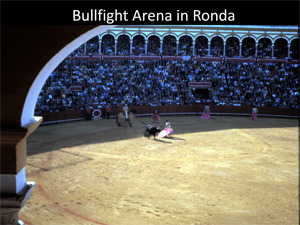

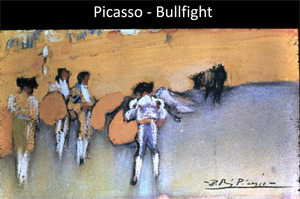

The ‘Olé, Olé’ of the bullfights may be a reminiscent cry of ‘Allah, Allah’ – a theme taken up by García Lorca in the “Lament for Ignazio Sánchez Mejías”, his bullfighter friend who was gored to death during a bullfight. Bullfighting plays an important role for Spanish artists from Goya to Picasso, where the symbolism of the bullring, of light and dark, sol y somber (sun and shade) equals life and death. The bull is always killed in the shady side of the bull ring (the main bullfights always start at 5:00 p.m. in the afternoon) – sacrificed by the toreador/priest in an ancient ritual. Light and dark, day and night, sun and moon are always powerful forces in García Lorca’s work.

The ‘Olé, Olé’ of the bullfights may be a reminiscent cry of ‘Allah, Allah’ – a theme taken up by García Lorca in the “Lament for Ignazio Sánchez Mejías”, his bullfighter friend who was gored to death during a bullfight. Bullfighting plays an important role for Spanish artists from Goya to Picasso, where the symbolism of the bullring, of light and dark, sol y somber (sun and shade) equals life and death. The bull is always killed in the shady side of the bull ring (the main bullfights always start at 5:00 p.m. in the afternoon) – sacrificed by the toreador/priest in an ancient ritual. Light and dark, day and night, sun and moon are always powerful forces in García Lorca’s work.

Manuel de Falla: Homenaje, “Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy” (version for piano) (1920)

The poem starts again with an almost musical repetition throughout the entire first part of the poem – here of impending doom, like a death bell — ‘at five in the afternoon”:

| “A las cinco de la tarde. Eran las cinco en punto de la tarde. Un niño trajo la blanca sábana A las cinco de la tarde. Una espuerta de cal y prevenida A las cinco de la tarde Lo demás era muerte y sólo muerte A las cinco de la tarde | At five in the afternoon. It was exactly five in the afternoon. A boy brought the linen sheet At five in the afternoon. A basket of lime standing ready at five in the afternoon Everything was death, only death, at five in the afternoon.” |

The bullfighter’s death is lamented throughout the poem, but in the end, García Lorca resurrects him and his memory with this elegy — an absence and presence at the same time … the song makes him eternal.

The bullfighter’s death is lamented throughout the poem, but in the end, García Lorca resurrects him and his memory with this elegy — an absence and presence at the same time … the song makes him eternal.

In my last article, I had written about the close friendship between García Lorca and Manuel de Falla.

Born in 1876 in Cádiz, Manuel de Falla was also inspired and tutored in piano by his mother. He studied in Madrid under Felipe Pedrell, who introduced him to 16th century Spanish church music, folk music and the zarzuela, the Spanish form of opera.

In 1907, Manuel de Falla moved to Paris where he met Debussy, Ravel, and later, Igor Stravinsky. In 1914, he returned to Madrid. He wrote his first great pieces: two ballets, El Amor Brujo (Love, The Magician), which uses Andalusian folk music and El Corregidor y la Molinera (The Magistrate and the Miller’s Wife), which Diaghilev asked him to rescore for a ballet by Léonide Massine, then called The Three-Cornered Hat. Picasso created the sets and designs for this ballet production.

Manuel de Falla continued to compose masterpieces, such as Noches en los Jardines de España (Nights in the Gardens of Spain), evoking the very same Andalusian atmosphere in music, which García Lorca evokes in his poems. The Spanish classical guitar features prominently in his music, in particular in his Homenaje: Pièce de Guitare écrite pour “Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy”, later re-orchestrated as larger works in orchestra and piano versions.

Manuel de Falla: El amor brujo (Love, the Magician) (excerpts) (1915)

Manuel de Falla wrote Homenaje in Granada in 1920 (Claude Debussy had died in 1918), in the house of García Lorca’s family, as an elegy, similar to Lorca’s elegy for Ignazio Sánchez Mejías. He uses a Habanera rhythm (which is not sad, but rather somewhat lively), but nevertheless conveys a feeling of grief conveyed by a ‘glissando’ in the composition which takes its inspiration from the ‘cante jondo’ of the flamenco tradition. This duality reflects again the Moorish tradition of art and song. An irregularity is created in that the notes in the score, marked with an x, should be held back, creating a notion of suspense, of time suspended, which are then contrasted with the strict tempo of the Habanera in another part of the composition. This feature of the piece is particularly important in the guitar version (for a detailed discussion of the piece, please read Rey de la Torre’s discussion with Walter Spalding on guitarist.com).

Manuel de Falla wrote Homenaje in Granada in 1920 (Claude Debussy had died in 1918), in the house of García Lorca’s family, as an elegy, similar to Lorca’s elegy for Ignazio Sánchez Mejías. He uses a Habanera rhythm (which is not sad, but rather somewhat lively), but nevertheless conveys a feeling of grief conveyed by a ‘glissando’ in the composition which takes its inspiration from the ‘cante jondo’ of the flamenco tradition. This duality reflects again the Moorish tradition of art and song. An irregularity is created in that the notes in the score, marked with an x, should be held back, creating a notion of suspense, of time suspended, which are then contrasted with the strict tempo of the Habanera in another part of the composition. This feature of the piece is particularly important in the guitar version (for a detailed discussion of the piece, please read Rey de la Torre’s discussion with Walter Spalding on guitarist.com).

García Lorca and Manuel de Falla’s friendship was truly one of reciprocal inspiration… they can be considered two of the greatest Spanish artists of the 20th century.

I return to Garcia Lorca’s poetry over and over again for the sheer pleasure of it. I can never be level-headed or academical about him,- he’s just pure beauty for me.

Thank you for the article.