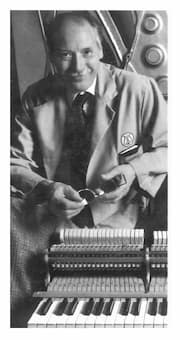

Franz Mohr

One very special person has played more in Carnegie Hall than all pianist superstars put together. His name was Franz Mohr, and he was the piano tuner to the stars. You see, he was the chief concert technician for Steinway & Sons for 24 years. As the close colleague of legendary musicians such as Vladimir Horowitz, Arthur Rubinstein, Glenn Gould, Rudolf Serkin and many others, Franz Mohr attended to their Steinway instruments, making delicate adjustments that affect tone, balance, and other characteristics of sound. It was Mohr who enabled these virtuosos to fully realize their own, individual interpretative styles, and to fully realize their concept of tonal color. Mohr was born in Duren, Germany on 27 September 1927 and he studied music at the Conservatory in Cologne and the Academy of Music in Detmold. Mohr trained to be a violinist, but he “developed a serious problem with his left wrist. “I was taking breaks and treatments and finally I had to come to the conclusion—after being already twenty-three or twenty-four years old and having sat in a string quartet—I had to give it up! I saw an ad in the paper; some people at the Ibach piano factory were looking for apprentices and I thought that has still something to do with music! So I went into it and I just loved it. I was working with my hands and worked my way up.”

Horowitz Plays Variation on a Theme of Bizet’s Carmen

Vladimir Horowitz

In 1962, Mohr made his way to the United States and became the assistant to Bill Hupfer, who was the Chief Concert Technician at that time. “Bill was a real legend. He had tuned for Paderewski, Myra Hess, and he traveled all his life with Rachmaninoff, and later he had Horowitz. A few years later I simply inherited all those people, like Rubinstein and Rudy Serkin and Horowitz. Mohr probably worked most closely with Vladimir Horowitz, and through their collaborations we are able to gain deep insights into the pianists’ character and thoughts.” Mohr tells the story that they were in Rochester “and just before the concert Horowitz went out onstage he was nervous, and I always had to hold his hands. He was always very cold and he said, “I admire you with your warm hands. Hold my hands!” But just before he walked out onstage to that lonely piano, he turns to me and he said, “Franz, it’s the most lonely place in the world,” and I said, “Oh, thank you, Lord, I’m just the piano tuner! I don’t have to work out there!”

Horowitz: Piano Recital 1987

Mohr’s devotion to Horowitz extended after the pianist’s death to keep his piano in perfect playing condition. “To this very day,” Mohr explained, “I still tune the piano in the Horowitz home, every month. Nobody plays it, but we keep it up.” Bill Hupfer initially took Mohr to the Horowitz residence, “but Horowitz didn’t even show his face. He was very much in seclusion at that time, although he did recordings. It took quite a few months; then all of a sudden, when I was in the home and had tuned the piano, he came down. I guess I was lucky enough that he liked me, and from that time on he always would come down as soon as he heard me finishing up my tuning. He would come down and talk or play.” Horowitz, like a good many pianists, used a different piano for touring and another one for recording. In all, he used about six pianos, and no two pianos are exactly alike. “Horowitz’s taste changed over time as the very, very super brilliant sound, which at one point he liked very much, gave way to much more mellow sound. Since it is impossible to give every piano the same touch, Horowitz selected the pianos that would come closest to what he wanted, and then I regulated them. Then there’s still a way to go to build the tone, which he likes, but a piano is born a certain way and you have to work with what is there.”

Mohr’s devotion to Horowitz extended after the pianist’s death to keep his piano in perfect playing condition. “To this very day,” Mohr explained, “I still tune the piano in the Horowitz home, every month. Nobody plays it, but we keep it up.” Bill Hupfer initially took Mohr to the Horowitz residence, “but Horowitz didn’t even show his face. He was very much in seclusion at that time, although he did recordings. It took quite a few months; then all of a sudden, when I was in the home and had tuned the piano, he came down. I guess I was lucky enough that he liked me, and from that time on he always would come down as soon as he heard me finishing up my tuning. He would come down and talk or play.” Horowitz, like a good many pianists, used a different piano for touring and another one for recording. In all, he used about six pianos, and no two pianos are exactly alike. “Horowitz’s taste changed over time as the very, very super brilliant sound, which at one point he liked very much, gave way to much more mellow sound. Since it is impossible to give every piano the same touch, Horowitz selected the pianos that would come closest to what he wanted, and then I regulated them. Then there’s still a way to go to build the tone, which he likes, but a piano is born a certain way and you have to work with what is there.”

Rubinstein Plays Chopin

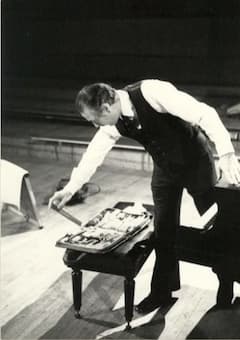

Franz Mohr at work © Crescendo

Apparently, Mohr was not allowed to utter the name of Arthur Rubinstein in Horowitz’s presence. But as a piano technician to both, Mohr was clearly attuned to some differences between these pianistic superstars. “Horowitz needed to play an easy action piano while Rubinstein wanted a piano with resistance; Horowitz had better technique and his style of play was electrifying while Rubinstein communicated music in a marvelous way, with a better tone born from cantabile singing. And finally, Rubinstein was a people person always greeting and chatting with strangers who recognized him, while Horowitz was shy and afraid of strangers.” At any rate, Horowitz was certainly a bit of a diva, and he had his beloved Dover sole flown in every day during a concert tour in Russia. Yet, Horowitz also had a less agreeable side to his personality. Mohr relates that during a black tie function, Horowitz put his finger straight into Mohr’s face and shouted, “I don’t’ want to see you. You remind me of work. I hate work.” Horowitz was also known for his tantrums in the studio, and there was a big fight in Milano, when Horowitz was playing Mozart with the Scala Orchestra and Giulini conducting. “There was always that G-sharp. He was fighting with Tom Frost, the producer, and he said, “Franz, that is not loud enough! Bring it up! Bring it up!” And Tom would say okay and I would go down there, sometimes even with the orchestra sitting there, and do something, which brought it up a little bit louder. But it was not loud enough. So then Tom Frost would say to me, “To my ears, that sticks out! Franz, it is impossible! You have to take it down!” So I’d go to take down again. Then Horowitz always said it was not enough! They went on for days. I said, “Tom, you tell him! You are the producer. I can’t be in between all the time!”

Horowitz Plays Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23, “Andante”

© Crescendo

Piano technicians are generally very happy to operate in the background. The only time Mohr sat in the hall during a concert was in Chicago at Orchestra Hall. Horowitz always loved to play there because he thought the acoustics to be just right. Mohr recalls, “But things were very tense at that time, even in the rehearsals. He had to live up to that tremendous reputation which he had built. But one day he said to me, “I have a ticket for you. Everything is fine with the piano. You sit the first tier there.” Then he played his first piece, which was a Haydn sonata. It wasn’t even Scarlatti! But I remember he went backstage after the first piece, and for the longest time he didn’t come onstage to go on with his program! I had already funny feelings, you know! Sure enough, the door opened in back of us and they said, “Is the piano tuner here?” So I run, and it took quite some time to get downstairs and then backstage. Horowitz was furious! He said, “I played so many wrong notes! Somebody touched my stool! It’s much too high, it’s much too high!” So I said, “Maestro, what do you want me to do?” He said, “Lower it! Lower it!” I said, “But how much?” Well, then he showed me with his fingers, about a quarter of an inch. So I walked out onstage to lower it, and of course you know what people thought. The performer always comes on and they clap. I took a few bows! So I adjusted the chair, and from that time on, I never ever went into the audience. Always I’ve been backstage. It was much more comfortable if he needed me for something.”

Horowitz Plays Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3

Mohr famously wrote, “I play more in Carnegie Hall than anybody else, but I have no audience.” Like any good piano technician, Mohr isn’t tied to a particular location and office hours, but he also makes house calls. He was invited to the White House when Van Cliburn played for Gerald Ford in 1975, and in 1987 when Mikhail Gorbachev visited Ronald Reagan. Mohr’s office used to be in the old location of Steinway’s Manhattan showroom, merely steps away from Gary Graffman’s apartment on West 57th Street. Whenever there was a problem, Mohr was onsite. “If he came because I broke strings, he would replace the strings,” Mr. Graffman said in an interview. “But if more extensive work was needed, he would take out the insides of the piano and carry it half a block to the Steinway basement. He would work on it and carry it back.” Sadly, Franz Mohr recently passed away, but his son Michael has stepped into his father’s footsteps and he is director of restoration and customer services at Steinway.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Graffman Plays Prokofiev’s Piano Concert No. 4

At a dinner following a successful concert, Vladimir Horowitz intoned, “Franz, you are the most important man in this room”.