© University of North Carolina at Greensboro UNCG Cello Music Collection

Ralph Kirshbaum: Walton Cello Concerto: I Moderato

Lynn Harrell and Pinchas Zuckerman: Brahms Double Concerto: I Allegro

Lev’s earliest memories are of deportation. The Aronson family hailed from Mitava, a small town, which borders Lithuania, the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Riga. Lev’s parents, a tailor and a seamstress, were amateur musicians. One could hear everything from Schubert lieder, violin playing, and klezmer music in their home. In order to further their skills, the family traveled to Germany and enrolled in the School of Fashion Design. There in 1912, Lev was born. The First World War broke out soon after the family returned to Mitava. The town, inundated with refugees, deported 40,000 Jewish citizens in crowded cattle cars, Lev’s family among them. They disembarked in Voronzeh, a dismal city located a few hundred miles from Moscow.

Lev received his first cello lessons there after hearing a classmate play the cello and falling in love with the instrument. But in 1918 persecution again reared its ugly head, and the family moved back to Latvia, settling in Riga. Lev resumed his cello studies with Paul Berkowitsch, a medical doctor who had studied at the St Petersburg Conservatory and with Julius Klengel. One day, they had the opportunity to hear the principal cello of the Berlin Philharmonic, charismatic cellist, Gregor Piatigorsky, perform in recital. That concert changed Lev’s life.

When Lev was sixteen years old he was accepted by the University of Berlin to study law. He was anxious to right wrongs, which he himself had experienced. A chance encounter in 1929 with an amateur orchestra led him to an introduction to Julius Klengel who was still teaching in Leipzig. Klengel thought very highly of the boy’s talent. After a year of studies, Lev switched to Berlin’s Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory, where Piatigorsky was teaching.

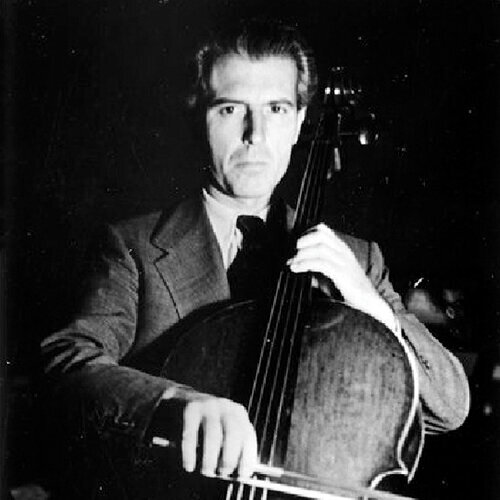

Lev Aronson with Joseph Schmidt

© June 8, 2017 Patron magazine

Aronson began to concertize in the 1930s as the political situation in Germany worsened. Somehow, he acquired a priceless Amati cello. Perhaps his father raised the money, or Piatigorsky loaned the instrument to Lev. Perhaps he acquired it when eminent artists were fleeing Europe, who sold their instruments for quick cash. Lev, who had blond hair and blue eyes, thought he could continue his career but violence and chaos was all around him. With Jewish people boycotted, beaten, or worse, Lev returned to Riga in 1933.

Listen to Lev here.

He continued to perform and play chamber music, making several recordings for the Bellacord Electro label and in 1937, he became principal cello of the Libau Philharmonic Orchestra. Within the year, Jewish artists and Jewish music were prohibited. No Latvian orchestras or conservatories would hire him. By 1938 Lev barely eked out a living teaching a few students. In 1941 the German army invaded Latvia bombarding the city. The Aronsons didn’t dare venture outside. Then, a knock on the door. “Two Latvians wearing armbands, one holding a document: Are you the cellist? You have two cellos, four bows, and cases. Get your instruments. Follow us,” and with that Lev was marched to the post office, the repository for looted possessions. He later recalled the grief-stricken faces of other musicians, and being pushed down a long staircase.

Lev was rounded up for the most inhuman slave labor and incarcerated in a series of concentration camps. Once he had one hour only, to load and unload a truck with rocks, or he would be shot. Lev concentrated on three 20-minute cello pieces as his stopwatch, the melodies swirling in his thoughts. Music saved his life. By the end of the war, 25 members of Lev’s family had perished, including his parents and his sister. Lev was convinced that his hands were permanently ruined by the brutal toil and four years without a cello.

Aronson painstakingly built back his health and his technique, on cellos he found in the rubble—instruments covered in soot, missing strings, and with holes in them. Piatigorsky came to the rescue when in 1948, Lev and his wife Nina emigrated to New York. Piatigorsky bought Lev an adequate cello, a bow, and promised to help him find employment, by arranging auditions and introducing him to contractors. Lev, plagued by nightmares, worried about money, about learning English, and whether he could restore his technique, practiced like a fiend. Fortunately, he encountered a sympathetic voice—Antal Dorati, the Hungarian conductor who was rebuilding the Dallas Symphony. Dorati had engaged Janos Starker as principal cello, and Aronson would be the assistant principal.

In 1949, Starker left Dallas to become the principal cello of the Metropolitan Opera. Aronson took over as principal cello, a position he held until 1967. That year, he joined the faculty of Baylor University, Waco, Texas, and in 1980 he became professor of cello at the Meadows School of the Arts, Southern Methodist University, in Dallas.

Sometimes his heavy accent made him sound like a task master, “Show me where in the score it says, ‘batter the cello!’” Harrell recalls, “Lessons sometimes lasted over two hours… Lev was totally captivating and a mesmerizing influence.” His passion for music was remarkable.

In the 1970s, Aronson collaborated with cellist Rudolf Matz and published “The Complete Cellist,” a two-volume book on cello technique.

One of the most influential cello teachers of the twentieth century, since 2013, the Lev Aronson Legacy Festival has been held at the Meadows School of the Arts to celebrate the master, and to spread his passion for teaching the cello. Artistic Director Brian Thornton hopes Aronson’s story will inspire people—art and music can make a positive difference in the world.

For more about Lev Aronson’s remarkable life, “The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson” by Frances Brent is a beautifully written tribute.

Lev Aronson Legacy Festival

I have met and had a nice conversation with Mr. Aronson after a competition in Dallas in 1972. (first prize).