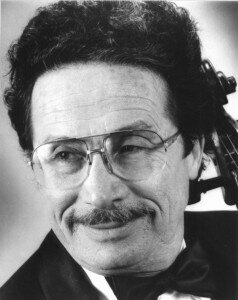

Hungarian cellist Laszlo Varga escaped war-torn Budapest, and Nazi forced labor, to become principal cello of the New York Philharmonic, a recitalist, quartet player, and revered teacher. He was born in Budapest in 1924, surrounded by music—his father was an amateur violinist, his mother an excellent pianist and art teacher, and his sisters were talented violinists.

Hungarian cellist Laszlo Varga escaped war-torn Budapest, and Nazi forced labor, to become principal cello of the New York Philharmonic, a recitalist, quartet player, and revered teacher. He was born in Budapest in 1924, surrounded by music—his father was an amateur violinist, his mother an excellent pianist and art teacher, and his sisters were talented violinists.

Beginning his cello lessons at age seven, Varga continued advanced studies at the famed Franz Liszt Academy—the conservatory where both Janos Starker, (who also was born in 1924) and my father, (born in 1922) all studied with Adolf Schiffer, and with composers Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, and Léo Weiner. Varga became the principal cello of the Budapest Symphony in 1940 as the war was raging. On March 19, 1944, the Nazis invaded Hungary and stopped a Sunday performance, firing and subsequently rounding up all Jewish musicians, including Varga and my father.

Varga came to live in the United States by happenstance. The Léner quartet, a very well-established and internationally renowned string quartet, who had moved to the U.S. during the war, suddenly needed a cellist. The first violinist would only consider a cellist who had studied with Léo Weiner. Varga got the job sight unseen. The first engagements for Laszlo was a concert tour in Switzerland in 1946—the first time he was out of Hungary, seven days of fiendishly long rehearsals, followed by 27 concerts in less than one month. Their touring then took them to South America. When Léner died in 1948 the quartet disbanded, leaving Varga in New York.

Like other newcomers he had to wait several months to join the musician’s union. An avid amateur violinist and patron of the arts invited Varga to play chamber music in his home. Why not? He had thought. The patron, it turned out, had some important friends. Varga met and played with Isaac Stern, Heifetz, Milstein, Piatigorsky, Primrose, Leonard Bernstein, and other great artists.

Like other newcomers he had to wait several months to join the musician’s union. An avid amateur violinist and patron of the arts invited Varga to play chamber music in his home. Why not? He had thought. The patron, it turned out, had some important friends. Varga met and played with Isaac Stern, Heifetz, Milstein, Piatigorsky, Primrose, Leonard Bernstein, and other great artists.

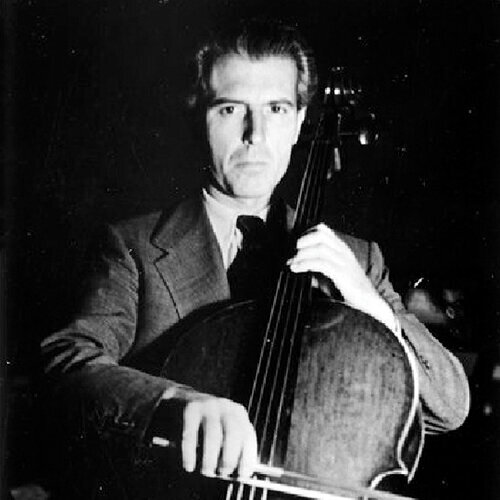

When Leonard Rose decided to retire as principal cello of the New York Philharmonic, Varga auditioned and won the position, which he held for 11 years under two great conductors, Mitropoulos, and later, Bernstein, and he performed as soloist with the orchestra many times.

Schumann: Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op. 129

Varga became interested in writing musical arrangements for cello ensemble, and to expand the cello literature. He formed the first cello quartet in America with three other cellists from the New York Philharmonic, and together they performed and recorded works such as the Bach Chaconne, from the Partita No. 2 in D minor originally for solo violin, for four cellos. Laszlo eventually wrote over fifty arrangements—for cello solo, duos, quintets, ensembles for multiple cellos, (which he loved to conduct) works originally written for orchestra arranged for cello and piano, and vocal music. Varga audaciously arranged the Beethoven Violin Concerto for cello and Béla Bartók’s Sonata for Solo Violin for a Five-Stringed Cello. It looks difficult! This work and the entire Laszlo Varga Musical Score Collection—34 boxes of music—is currently housed at the Martha Blakeney Hodges Special Collections and University Archives at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, NC, USA.

Bach: Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: V. Ciaccona (arr. for 4 cellos by Varga)

Bach: Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor, BWV 1004: V. Ciaccona (arr. for 4 cellos by Varga)

In 1962 Varga left the Philharmonic to return to his first love—playing chamber music and to endeavors he was becoming interested in like conducting. He joined the Canadian String Quartet and taught at the University of Toronto for a brief time before he was invited to San Francisco State University to lead the first-rate symphony orchestra, and become the professor of cello and chamber music.

Varga became known for being able to learn difficult music quickly and he premiered several new works. He was often called upon for a last-minute replacement of a musician who was suddenly indisposed. During a 2002 interview, he told a hilarious story to Tim Janof of the Internet Cello Society. “Once, when I was teaching at a summer chamber music festival at the University of Houston, one of the six student groups almost had to cancel their performance of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet. They didn’t appear on stage when they were supposed to, so I went backstage to find out what was going on. I discovered that the violist had a sudden attack of carpal tunnel syndrome …and she couldn’t play. To remedy the situation, they sent for the viola teacher, who offered to sit in her place. When the teacher arrived, she looked at the music, and said, ‘I’ve never played this before. I don’t feel comfortable sight-reading this for a concert.’ I then asked her, ‘Are you willing to lend me your viola?’ Though bewildered by my offer, she handed it over and I walked out on stage and played the viola in my lap as if it were a little cello. I had no trouble at all because violists often missed classes when I was teaching and I often stood in for them…”

In his teaching studio, Varga had a motto: “God gave you a fourth finger so use it.” Unlike other cellists, Varga advocated using the fourth finger in the upper positions, whereas most of us do not. No wonder he could negotiate pieces not originally for cello—by Ravel, Stravinsky, Debussy, Mozart, and Schubert! He might have offended purists but he loved music, and thought they sounded great on the cello.

Saint-Saens: Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 33

He was an adventurous performer who lived with joie de vivre, who concertized on several continents, made numerous recordings, and touched countless lives. “Cellobrations” and groups such as the Yale Cellos, often include music arranged by Laszlo Varga. He passed away just short of his 90th birthday.

In December of 2014, conductor Kent Nagano, a former student of Varga, was quoted in the New York Times after Mr. Varga’s death: “Mr. Varga was one of the exceptional influences who, through his impatience, joy, intolerance of mediocrity, discipline and love of art, taught me those things which last a lifetime — that music is a metaphor for life and as such must be cherished, respected, shared and actively lived to its fullest every day.”

Debussy: Sarabande (arr. Laszlo Varga) 14 cellos

You May Also Like

-

Forgotten Cellists: May Mukle In 1909, May Mukle, one of the first female British cellists to achieve international acclaim

Forgotten Cellists: May Mukle In 1909, May Mukle, one of the first female British cellists to achieve international acclaim -

Forgotten Cellists: Bernard Greenhouse The acclaimed Beaux Arts Trio toured worldwide for nearly five decades

Forgotten Cellists: Bernard Greenhouse The acclaimed Beaux Arts Trio toured worldwide for nearly five decades -

Forgotten Cellists: Enrico Mainardi Born in 1897 in Milan, the Italian cellist Enrico Mainardi had a small cello

Forgotten Cellists: Enrico Mainardi Born in 1897 in Milan, the Italian cellist Enrico Mainardi had a small cello -

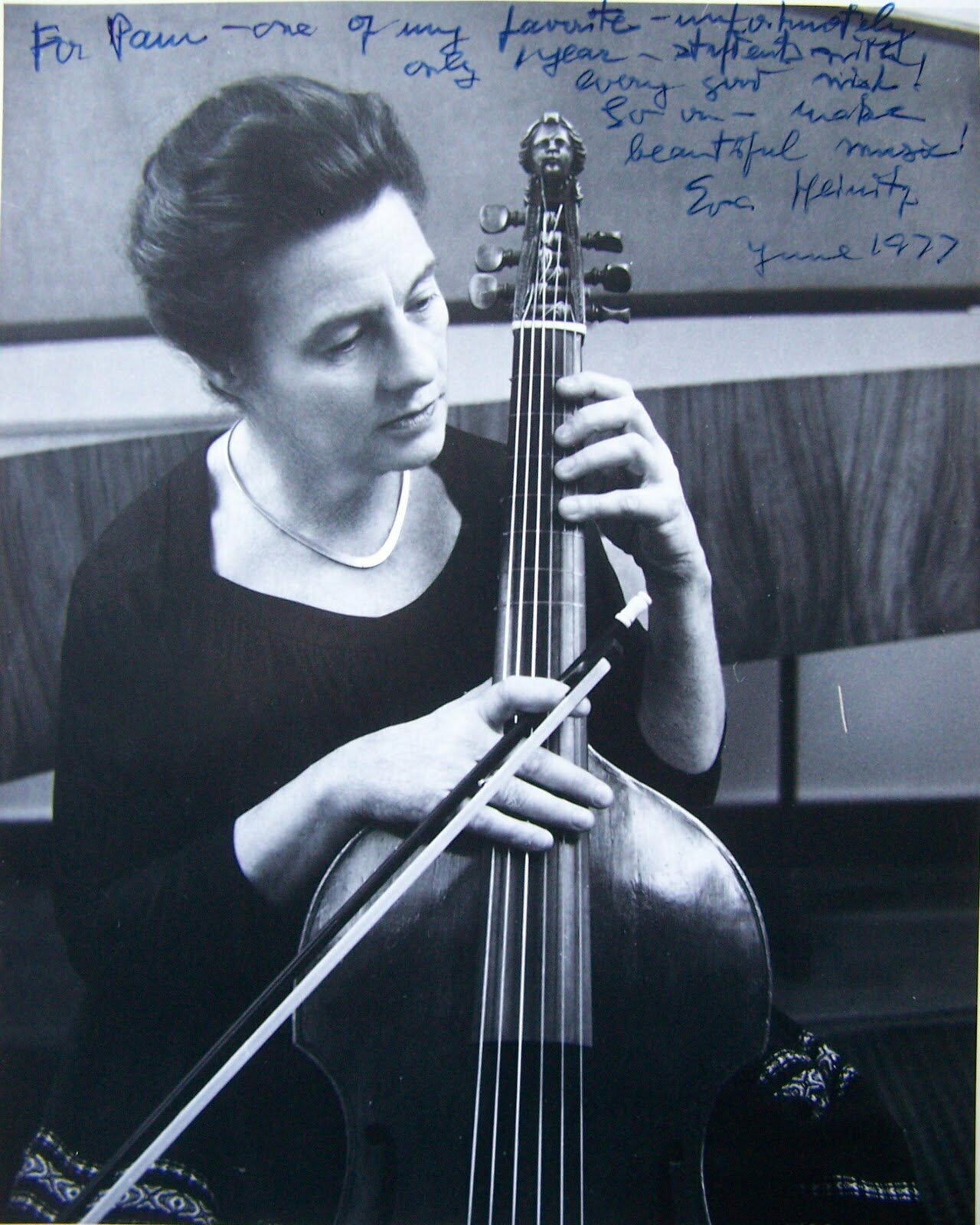

Forgotten Cellists: Eva Heinitz Eva Heinitz, cello soloist of international repute, who performed chamber music with violinists

Forgotten Cellists: Eva Heinitz Eva Heinitz, cello soloist of international repute, who performed chamber music with violinists

More Blogs

-

Best Quotes from Chopin’s Letters: Emotional, Witty, and Heartbreaking Explore his innermost thoughts and personality

Best Quotes from Chopin’s Letters: Emotional, Witty, and Heartbreaking Explore his innermost thoughts and personality - Buzz, Flutter, and Crawl

Celebrate National Be Nice to Bugs Day (July 14) Discover Chopin's Butterfly Etude, Bartók's Diary of a Fly and more -

Three Violinists Who Survived the Nazi Concentration Camps Stories of Sandor Braun, Helena Dunicz-Niwińska, and Abram Merczynski

Three Violinists Who Survived the Nazi Concentration Camps Stories of Sandor Braun, Helena Dunicz-Niwińska, and Abram Merczynski -

What Was It Like Being Liszt’s Student? Inside stories of the legendary composer's teaching methods and personality

What Was It Like Being Liszt’s Student? Inside stories of the legendary composer's teaching methods and personality

Interesting articles.