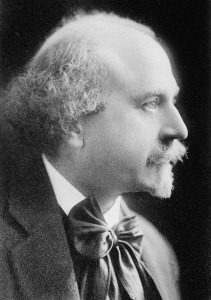

Arthur De Greef

De Greef continued his training in Weimar, studying for two years with Liszt. He toured Europe and North Africa and also gave concerts with Camile Saint-Saëns. His reputation was as a self-effacing and eloquent performer who enjoyed the approval of composers such as Grieg, who considered de Greef’s rendition of his piano concerto the finest he had heard. As his reputation grew, many composers began to write for him and he numbered among his friends some of the greatest composers of his day: Brahms, de Falla, Busoni, Pugno, Cortot, Paderewski, Rachmaninov, Ysaÿe, Gounod, Ambroise Thomas, Elgar, and von Bülow. This international set of composers can be matched with the international set of performers, including Caruso, Melba, Chaliapin, Gigli, and many others.

The clarity and simplicity of his performance can be heard in this final movement of the Grieg Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 16. He was the first to record this work in its entirety, without any cuts.

Grieg: Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 16

At age 30, De Greef took up composition himself and, although Saint-Saëns thought he had the potential to become a great composer in addition to being a great pianist, his works do not catch the feelings as a great composition should. It’s agreed that they are virtuoso works that require a virtuoso at the keyboard, but, ultimately, they are not long-lost masterpieces of the concerto repertoire that they might be. Here is the slow movement of his first Piano Concerto, and we can hear the careful placing of the string and piano voices, and yet it seem to be held at a distance from the music. The work was dedicated to Saint-Saëns.

De Greef: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor: III. Andante (André de Groote, piano; Moscow Symphony Orchestra; Frédéric Devreese, cond.)

He didn’t only write piano concertos, but many other works, including orchestral works and chamber music, all of which has fallen out of the repertoire. It’s rare that a performer with such a universal reputation would fail so utterly as a composer, particularly in a genre such as concerto of which he was a virtuoso.

Why ‘forgotten pianists’? Most of the named pianists in your article are the immortals of the recorded history of piano playing; I once gave a series of three broadcast talks for the BBC entitled ‘The Changing Art’, in which I introduced records of great pianists from the early days of recording to the last recordings of Arthur Rubinstein, so as to illustrate the radical changes in interpretative approach that had taken place during that period. Rosenthal’s first name was Moritz, by the way, not Morris.

And Wanda Landowska is mainly remembered as a harpsichordist.