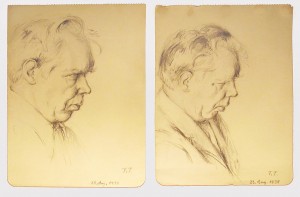

Two drawings of pianist Edwin Fischer by the German artist and musician Fritz Tennigkeit (1892 – 1949)

His particular area was music of the Baroque and early Classical era, hence his interest in Bach. He was one of the first to start to look at performance practice of the earlier eras, joining other performers such as Arnold Dolmetsch and Alfred Deller who started to experiment with the interpretation of earlier music. We wouldn’t necessarily look at Fisher’s work today as being historically true, particularly in view of current research, but he did return to such classical norms such as conducting from the keyboard, as in this performance of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25 with the Vienna Philharmonic.

Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 25 in C Major, K. 503: II. Finale: Allegretto (Edwin Fischer, piano; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Edwin Fischer, cond.)

In 1931, Fischer began a long association with the HMV recording company, recording for them for the next 11 years and resuming again after WWII. His recording of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier is considered a landmark – his was the first full recording and still remains one of the finest recordings of the work.

Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, BWV 846-869: Prelude No. 1 in C Major, BWV 846 (Edwin Fischer, piano)

Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, BWV 846-869: Fugue No. 1 in C Major, BWV 846 (Edwin Fischer, piano)

His textures are clear, he brings humour to a work that in others’ hands can become grim, and each voice is kept clear and separate.

One critic viewed Fischer as ‘represented an ideal middle ground between objective intellectualism and unabashed romanticism.’ Noted pianist and critic Paul Badura Skoda wrote of Fischer: ‘One hesitates to refer to a concert artist as a “genius”. But when Fischer played, he convinced his audiences that interpretation can and should be a creative art. In his view, to “create” and to “re-create” were practically synonymous. There were moments of indescribable emo¬tional ecstasy in his performances, moments when he became a prophet. The listener stopped taking notice of the instrument and the performer when the music began flowing directly into his soul in its own idiom, pro¬ducing a kind of religious experience.’

No one who heard, live, any of the pianists listed – and I heard Ney, Solomon, and Bachauer in the flesh, and others on the radio, would accept they are in any way “forgotten”. Even if you only heard most of them on disc – these days easier than it ever was. And it was MORITZ Rosenthal – not “Morris”