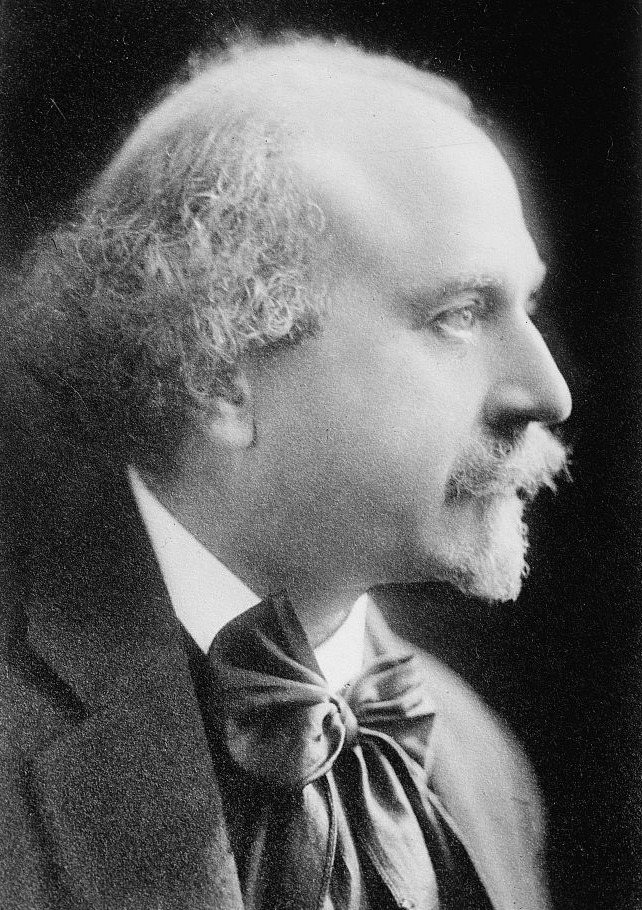

Ignace Tiegerman

Credit: http://www.egy.com/

The majority of his recordings were made in his house, rather than in recording studios, so their quality isn’t of the best.

Tiegerman was a student of Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna but it is through his work with Leschetizky’s assistant, Ignaz Friedman, that was more influential. By his mid-teens, Tiegerman was already considered capable of handling Vienna’s large concert halls. Although in the 1920s many of his contemporaries were already relocating to America, Tiegerman decided to go to Egypt instead. By 1934, the Conservatoire Berggun had become the Conservatoire Tiegerman and by the 1960s, it was one of the only remaining conservatories in the city.

Vladimir Horowitz viewed Tiegerman as his greatest competitor and is said to have been thankful that he had taken up residence in remote Egypt rather than in New York.

He made few public appearances, but when he did perform, it was to a full house. It is said that the rarity of his appearances had to do with the size of his fee – even if he was a local performer, he insisted that the Egyptian Symphony Orchestra pay him as much as if he were coming from Europe.

He had a special affinity for the music of Chopin, a fellow-countryman of Poland. One of his most important performances was for the centenary of Chopin’s death, held at the Royal Opera House in Cairo in 1949.

In the recording of this Chopin Etude, you can hear Tiegerman speaking at the end.

His pupils in Egypt recalled a teacher who, unlike other teachers, didn’t have them spend hours on scales or exercises, but took them directly to the music. ‘After a few lessons, if you were lucky to be accepted as his student, you entered a new universe, the universe of music. You started understanding why Chopin wrote the way he did, why Beethoven put a pause after this note, what is legato, and so on, and so on.’ said his student, Stephen Papastephanou. Another student recalled the price of not preparing for a lesson: the door of the studio would open, the score would come flying out, soon followed by the student!