Quatuor Calvet

Jean Champeil, Joseph Calvet, Maurice Husson and Manuel Recasens

Credit: http://www.rene-gagnaux.ch/

He didn’t know how lucky he was, to experience the thrill of history’s most music-obsessed century! The business side of music, royalties paid by publishers and concert organizers, finally started to break even, gradually replacing traditional aristocratic sponsorship. Scholars were salvaging folk music, and collecting instruments from across global colonial empires. Everywhere in Europe, Russia and the Americas, a career as a composer, virtuoso or teacher could be a passport out of poverty, and everyone was trying their hand at it.

Music benefitted from the social order prevalent until 1950: military hostilities were expected at short notice, and children as young as ten were deemed serviceable towards collective defence, albeit mainly as scouts and cadets.

Georges Bizet

Credit:Wikipedia

For those of limited financial means, public performance in churches, meeting halls, restaurants or street corners, offered the advantages of practicing from memory, sight-reading and improvising, while earning extra wages to relieve tight family budgets. After graduation, the luckiest could further improve their position through teaching, touring and landing a job with an orchestra or church – providing music for 200 weddings a year!

Financial incentives fuelled the careers of even the greatest: from the struggling Éric Satie (1866-1925), a busker and cabaret pianist into his mid-forties, surviving only by the generosity of admiring colleagues like Ravel, to the savvy Richard Strauss (1864-1949) who boasted about paying for a luxurious new home out of the proceeds of his titillatingly scandalous opera, Salomé (1905).

Again quoting the atheist, ever-lucid Bizet: “As a musician I tell you that if you were to suppress adultery, fanaticism, crime, evil, the supernatural, there would no longer be the means for writing one note.” This diagnosis, enunciated fifty years before the cataclysm of World War I, proved to be a more accurate basis for predicting the long term survival of music, than Brahms’ fretful speculations over a possible end to civilization.

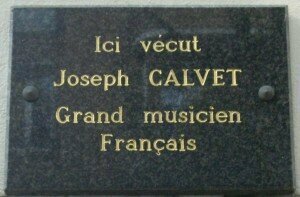

Joseph Calvet Memorial Plaque (at 2 Rue Gervais in Paris 17e)

Credit: Wikipedia

Debussy: String Quartet (recorded in 1931)

By the time Calvet graduated from the Paris Conservatoire in 1919, the century-old Franco-Belgian tradition of violin playing had continued to enhance its international prestige by officially adopting Belgian professor Lambert Massart’s aesthetic of sustained vibrato, and the further improved bowing technique developed by Lucien Capet in collaboration with bow-maker Arthur Vigneron (1851-1905) and his son André (1881-1924) – echoing Giovanni Viotti’s ground-breaking pre-French Revolution bowing innovations with bow-maker François Tourte.

Calvet was a disciple of Belgian violinist and composer, Guillaume Remy (1856-1932) a Massart First Prize pupil (1878), and contemporary of Ysaÿe in Liège. Remy premièred his own Piano Quintet, with dedicatee Camille Saint-Saëns at the piano, and fellow-Belgian violinist Martin Marsick (Marsick was Massart’s 1879 First Prize pupil, and became the Stradivarius-owning professor of future greats Jacques Thibaud, Georges Enescu and Carl Flesch; his reputation was ruined when he absconded with a married woman – the romance was short-lived, but he lost his lucrative teaching post and died in poverty!)

Upon graduating in 1919, Calvet formed an ensemble specialising in Beethoven Quartets, with violinist Georges Mignot, violist Léon Pascal and cellist Paul Mas.

However, it was only in 1928, coincidentally ahead of the death of the admired – yet intimidating – Lucien Capet, that Calvet felt they could accept an invitation by “music life coach” Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979) to perform a complete cycle of Beethoven quartets.

Ravel: String Quartet in F Major (recorded in 1946)

And it was in the 1930s, with Daniel Guilevitch on 2nd violin, that they made celebrated recordings of Beethoven, Debussy and Ravel quartets, and the Quintet by Florent Schmitt (1870-1958) – whose ballet “La Tragédie de Salomé” (1907) was the thematic and musical inspiration for Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913).

Schmitt: Piano Quintet, Op.51 – II Lent (Florent Schmitt & Quatuor Calvet, 1935)

At the approach of WWII, Quatuor Calvet disbanded, as 2nd violin Daniel Guilevitch (1899-1990) – a student of Remy and Enescu, and sometime accompanist to Ravel – fled the Nazis to the USA. Shortening his name to Daniel Guilet, he became concertmaster in Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra, and later founded the long-lived Beaux Arts Trio (1954-2008) with Casals-trained cellist Bernard Greenhouse and pianist Menahem Pressler who still performs, in his nineties!

Calvet’s violist Léon Pascal formed the Pascal Quartet (1941-1973), which enjoyed an enviable post-War reputation, not only in Beethoven, but also through an expanded range of recordings in the 1950s.

After initiating a Musical Youth Mouvement under the Occupation, Calvet reconstituted his quartet in 1944, with violinist Jean Champeil, violist Maurice Husson and cellist Manuel Recassens.

Recassens, in the 1960s, would famously try to return the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire to its glorious pre-WWI stature; however, government economic priorities, and decades of unrestricted export of Stradivarius and other precious violins, ultimately forced a concentration of the best local instrumentalists in the new Orchestre de Paris under Lucien Capet’s pupil, conductor Charles Munch.

Still regarded as the world’s foremost quartet between 1930-1950 – along with Belgium’s Pro Arte Quartet – many composers dedicated works to them, including: Vincent d’Indy, Marcel Delannoy, Jean Françaix, Florent Schmitt, Henri Sauget, Reynaldo Hahn and Guy Ropartz.

Calvet’s temporary ill-health forced the quartet to break up definitively in 1950, with remaining members regrouping as Quatuor Champeil, and continuing to produce high level performances and recordings.

Calvet would recover, and contribute another thirty four years to his art, as professor of chamber music at the Conservatoire (1935-68), and as a member of the jury of the Marguerite Long – Jacques Thibaud International Competition.

A memorial plaque on his former residence in Paris expresses the homage of the nation: Ici vécut Joseph Calvet, Grand musicien Français (Here lived Joseph Calvet, A Great French musician).

Calvet Quartet recordings continue to inspire amateurs and professionals, through their perfectly judged tempi, phrasing, blended colours and expressive insights.