Minimalism as a musical genre originated in the USA in the 1960s. It involves stripping music down to its bare essentials, to focus on pure sonic power, pulse and the internal processes of the music, without narrative or a defined goal. Its emergence marked a move by composers such as Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Philip Glass to turn away from the avant-garde and atonality and return to an age-old formula: rhythm + pitch = music. Its main features are “consonant” or pleasing harmony/tonality, steady pulse or the use of drones, and the repetition of simple motifs, phrases or small cells. Minimalist composers also looked east, to the rhythms, harmonies and idioms of Indian and Eastern music and incorporated these into their own works to create music.

Minimalist music remains perennially popular and the genre has been enthusiastically taken up by composers such as Michael Nyman, Arvo Pärt, John Tavener, Howard Skempton, Henryk Górecki, Ludovico Einaudi, and countless other imitators and extemporisers of the basic form. This article focuses on four American minimalist music composers, all masters of the genre.

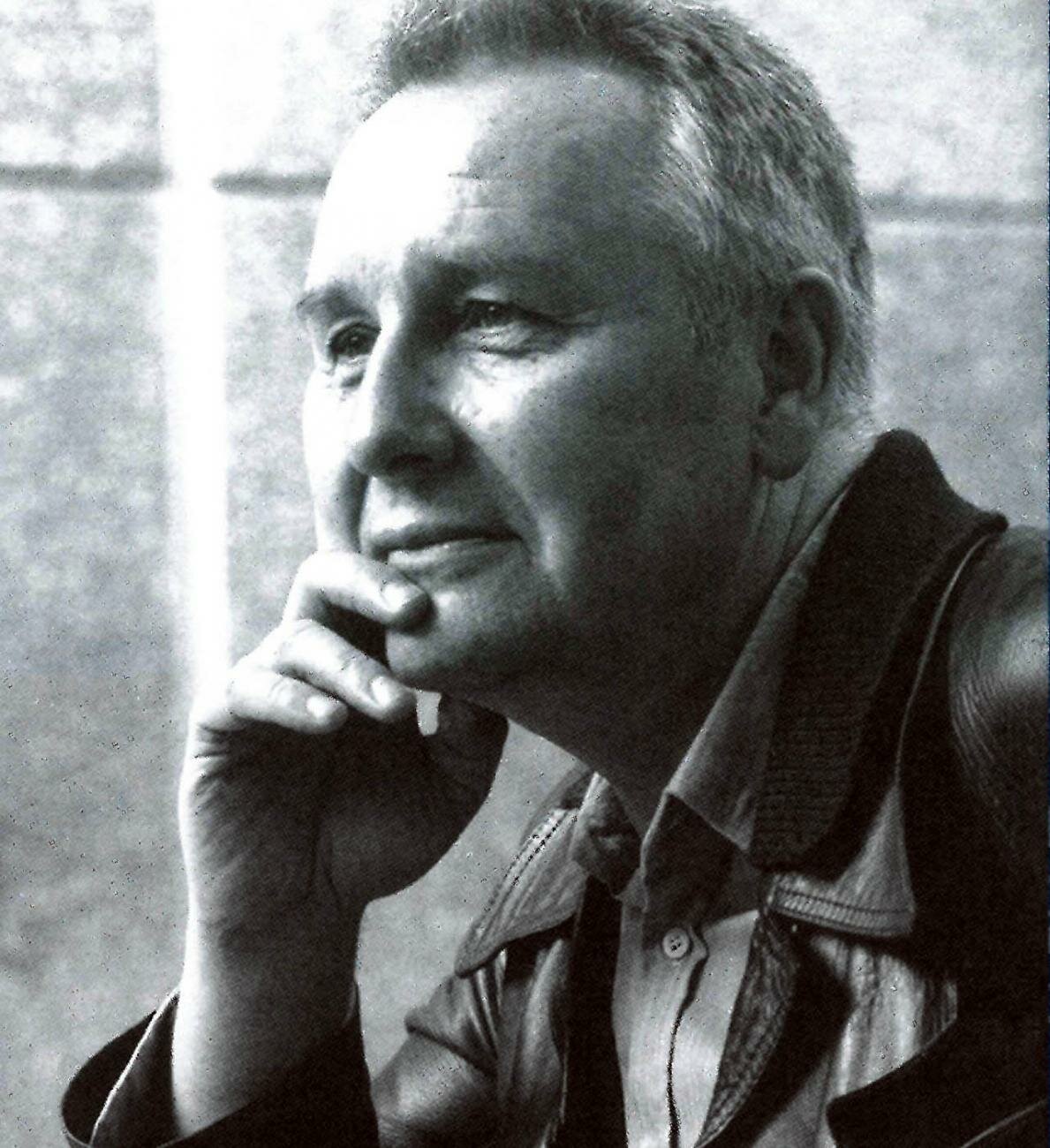

Steve Reich

Steve Reich: Music for a Large Ensemble (Steve Reich and Musicians)

Steve Reich

A pioneer of American Minimalism in the mid- to late-1960s, composer Steve Reich (born 1936) has been at the forefront of American avant-garde music ever since, and his influence crosses continents and musical boundaries. Drawing on both classical and non-Western influences, including Bach, Stravinsky and Bartók, John Coltrane, African drumming and Balinese gamelan, Reich’s music is tonal, harmonic, expressive and accessible, and his large and varied output demonstrates that Minimalism is far more than just repetitions or a fleeting musical trend.

His distinctive music is made up of repetitive patterns and pulses. He combines electronics, tape loops, phases, and fragments of speech or spoken word with traditional instrumentation to create complex textures and multiple shifting layers – hypnotic, engrossing music whose rhythms and patterns move in and out of synchronisation with one another, creating an ambiguous and intriguing range of timbres and effects which grow in complexity and variation. In a piece like ‘Piano Phase’, Reich transferred the techniques of electronic tape loops and phasing to real instruments: a sequence of pitches played on two pianos moving steadily in and out of sync result in a kaleidoscopic musical narrative.

‘Drumming’, perhaps his most seminal work and an example of “pure minimalism”, uses a single tiny rhythmic cell as the basis for an ambitious large-scale musical structure. ‘Different Trains’, a personal and deeply moving work, marks his return to the use of sampling where train whistles and interviews with Holocaust survivors are juxtaposed with writing for string quartet.

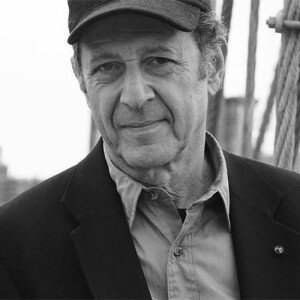

Philip Glass

Philip Glass: Mad Rush (Nicolas Horvath, piano)

Philip Glass

He used to work as a plumber and taxi driver; today he’s the undisputed master of Minimalist music.

Now in his 80s, Philip Glass is one of the most prolific and important composers of the 20th and 21st century, and his oeuvre encompasses solo works, symphonies, concertos, operas, chamber music, songs and film scores. Arguably, the most influential composer across the whole range of musical genres, his distinctive spooling, note-spinning, compulsively repetitive music has made an impression on Brian Eno and David Bowie, Aphex Twin and Nico Muhly, amongst others, and he enjoys a privileged position amongst contemporary classical composers in that his music is both listener-friendly and experimental.

While some find his music mechanical, cold and undemanding, others adore its complex yet subtle layers of atmospheric sounds and instrumentation, the hypnotic rhythms, piquant harmonic deviations – almost redolent of Schubert – and mesmerizing shifts in mood and intensity.

Meredith Monk

Meredith Monk: Between Song (Allison Sniffin, vocals; Kate Geissinger, vocals; Meredith Monk, vocals; Bohdan Hilash, clarinet; Allison Sniffen, piano; John Hollenbeck, bells)

Meredith Monk

Her vocal music is redolent of Hildegard von Bingen, performance artist Laurie Anderson and Liz Fraser of The Cocteau Twins, all rolled into one. Her piano music contains the meditative repetitions, loops and pulsations of minimalism, while her chamber music reveals striking dissonances and unusual instrumentation. Her musical roots lie in folk and rock music, whose idioms subtly infiltrate her oeuvre. One of America’s coolest composers, Meredith Monk defies categorisation.

Her pioneering interest in the range and capabilities of the human voice led her to develop what is now called “extended vocal technique”, which uses the voice as an instrument rather than the conveyor of words, and gives her music a universality which makes it sound both arcane and contemporary. She combines Medieval plainchant and oriental melodies with drones, wordless incantations, ululations and chattering murmurs. It’s direct yet lyrical, accessible yet otherworldly, serene yet challenging. Essentially tonal, her wordless music is powerfully communicative, arresting and transporting. As a cross-disciplinary artist who uses music, dance, film and performance, Monk has always taken on themes that can’t always be expressed but can be suggested through her work. Her distinctive music is just one fascinating facet of a much greater whole.

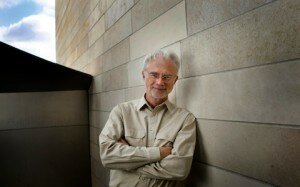

John Adams

John Adams: Grand Pianola Music – Part II: On the Dominant Divide (John Alley, piano; Shelagh Sutherland, piano; London Sinfonietta; John Adams, cond.)

John Adams

Half a generation younger than the founders of American Minimalist music, John Adams’ music perhaps falls more comfortably into the category of “post-minimalist”, but it’s a description which does a disservice to Adams’ vibrant creative output. While his music uses the hypnotic repetitions and loops, subtly shifting harmonies, and spooling melodies of minimalism, Adams successfully melds the rigorous purity of minimalism with a far richer palette, to create music which can be grand, inventive and dramatic, lushly textured, almost to the point of excess, emotionally expressive, or quietly moving and meditative.

Adams rejected atonality at a time when it was deeply fashionable and viewed by many as the only way to compose; instead his compositional language draws on the Classical tradition – at times deeply romantic – and also on American folk music, and pop. ‘Grand Pianola Music’, for example, mixes the heady late nineteenth-century romanticism of Rachmaninoff with Liszt-meets-Liberace virtuosity, the mesmeric minimalist conceits of Steve Reich, the subtle but piquant harmonic shifts of Philip Glass, and a memorably joyous major-key anthem.

In ‘Harmonielehre’ – a three-movement symphony in all but name – Adams pays homage to the monumental structures and opulent romanticism of Wagner, pre-atonal Schoenberg, Sibelius and Mahler (the second movement makes reference to the Adagio of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony). Its complex textures and haunting melodies are interwoven with Adam’s distinct use of sparkling percussion and hovering strings, from the booming, attention-grabbing chords and propulsive energy of the first movement to the finale which unfolds like the sunrise opening of Schoenberg’s ‘Gurrelieder’ before building to an astonishing, emphatic blaze of sound.