Foxtrot

The composer, conductor and educator Bernhard Sekles (1872-1934) caused a minor scandal in 1928. Sekles was director of the Hoch Conservatory of Music in Frankfurt am Main, and he decided to put Jazz on the curriculum. The courses in the theory and practice of jazz would be taught by Mátyás Seiber (1905-1960), and concerts held in the “Volksbildungsheim.” Seiber started his musical career at the Budapest Academy of Music. When he entered a wind sextet for a competition and was not awarded a prize, Bartók resigned from the jury in protest.

Mátyás Seiber

In 1927 he joined a dance orchestra on a transatlantic liner, and visited both North and South America. A cellist by trade, he perfected his skills as a jazz musician in various jam sessions in New York and elsewhere. Seiber immigrated to England in 1935 and he collaborated with Adorno on a jazz research project in 1936. In a lecture on jazz to the “Music of Our Time Congress,” he was demanding that jazz be “taken seriously and subjected to intelligent analysis, chiefly through an appreciation of its rhythmic techniques.” Seiber was also a capable composer and educator, and he published a number of didactic pieces, including his favorite, the foxtrot—tracks 1 and 4 in this recording.

Mátyás Seiber: Easy Dances (Goldstone and Clemmow)

Mátyás Seiber

Sekles and Seiber did not simply invent an academic subject; they responded to various musical stimuli and interests that were part of the musical and cultural fabric of the time. Six years earlier, Paul Hindemith had already caused a massive scandal with his Kammermusik No. 1.

The Amar Quartet in 1921 with Hindemith

in the center

At that time, a culture struggle was long underway as a critic wrote, “A hissing and seething begins, a pushing, shoving, and pulling, screams and shouts assault our ears; one sees sensuously distorted, common faces, hears whipping and blowing, laughter and shouts, groaning and rejoicing, whistling and yelling; pairs mingle in the most lascivious manner in what are literally foxtrot melodies, barbaric sound of half-engrossed, giddily reeling people are uttered…” The incorporation of the foxtrot in the last movement of this work clearly shocked listeners, but it was not a cheap and reckless joke on Hindemith’s part. For one, the foxtrot quotation is linked to its structural surroundings, and secondly, it is the counterpart of the “Ragtime” for large orchestra that Hindemith had composed in 1921. As Hindemith writes, “I cannot offer analyses of my works because I do not know how I should explain a piece of music in a few words. Besides, I believe that my things are really easy for people with ears to understand, so an analysis is unnecessary. People without ears cannot be helped even with such guides for idiots.”

Paul Hindemith: Kammermusik No. 1, “IV Finale: 1921” (Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra; Werner Andreas Albert, cond.)

Erwin Schulhoff

Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) was born in Prague and began his studies of composition and piano at the age of 10. Schulhoff was one of the first generation of classical composers to find inspiration in the rhythms of jazz music. He meticulously organized concerts of avant-garde music, and in 1919 authored the following manifesto. “Absolute art is revolution, it requires additional facets for development, leads to overthrow in order to open new paths… and is the most powerful in music…. The idea of revolution in art has evolved for decades, under whatever sun the creators live, in that for them art is the commonality of man. This is particularly true in music, because this art form is the liveliest, and as a result reflects the revolution most strongly and deeply–the complete escape from imperialistic tonality and rhythm, the climb to an ecstatic change for the better.” Schulhoff’s 1920 declaration that “Music should, first and foremost, produce physical well-being, ecstasy even, by means of rhythm” underlines his affinity with jazz, as does a letter to Alban Berg in which he writes: “I have an absolute passion for the dance in vogue and myself have times when I dance with bar ladies night after night – purely out of rhythmic intoxication and subconscious sensuality… Thereby I acquire phenomenal inspiration for my work, as my conscious mind is incredibly earthy, even animal as it were.” Composed in 1931, the Suite dansante en jazz is clearly indebted to jazz idioms, and the concluding Foxtrot was Schulhoff’s self-proclaimed “favorite dance rhythms.”

Erwin Schulhoff: Suite dansante en jazz, “Stomp, Strait, Waltz, Tango, Slow, Fox-trot” (Caroline Weichert, piano)

Alexander Tansman at the home of Vladimir Golschmann and his wife in St. Louis (U.S.A.) in 1931, watching while Prokofiev tries out Tansman’s Second Concerto on the piano. (Photo: Ruth Cunliff Russel, St. Louis, U.S.A.)

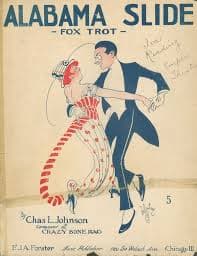

The origins of the Foxtrot are supposedly found with a Vaudeville actor born Arthur Carringford in 1882. He joined the circus early on, and when a music publisher liked his voice he was hired to sing songs in vaudeville theatres in San Francisco. Originally billed as “Mr. Frisky of Frisco,” Arthur eventually migrated to the East Coast and changed his stage name to “Fox.” When the New York Theatre was being converted into a movie house, management decided to try vaudeville acts between the shows. Harry Fox and his company of “American Beauties” were hired to provide the entertainment. As part of his routine, Harry Fox was doing trotting steps to ragtime music, which people referred to as “Fox’s Trot.” As the roof of the theatre was converted into a large dance floor, the “Foxtrot” became one of the featured dances in weekly dance contests. Mind you, there are various alternate histories regarding the origins of the foxtrot, but the dance quickly made it to Europe and found great popularity in the ballroom. And it also found it’s way into the toolkit of numerous composers across the continent.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Alexandre Tansman: Sonatine transatlantique, “Foxtrot” (Emma Schmidt, piano)