Kiss of Life

Franz Ignaz Danzi

Sinfonia concertante in B flat major, Op. 41

Wind Quintet in B flat major, Op. 56, No. 1

Between 1777 and 1778, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart spent a total of five months in the city of Mannheim. On one hand, he eagerly observed the pioneering musical efforts of the Manheim Orchestra, which included unified bowing, the independent treatment of wind instruments and the employment of a dedicated conductor. On the other hand, he fell passionately in love with Aloysia Weber. Given his initial romantic infatuation and his never-ending quest to secure a proper job, Mozart probably did not notice the unassuming fifteen year-old boy who had recently been invited to join the cello section of the famous Orchestra. Franz Ignaz Danzi (1763-1826), however, had no problems remembering Mozart’s visit! In fact, it served not only as the inspiration to publish his first compositions, but also was the defining moment that launched an extended and successful musical career.

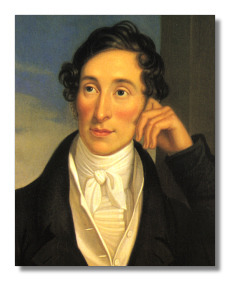

Carl Maria von Weber

Franz Ignaz received his initial musical instruction from his father Innocenz, who was one of the highest paid musicians at court. In fact, Mozart lavished high praise on Innocenz for his cello performance at the premiere of Idomeneo. Franz also took composition lessons with Georg Joseph Vogler, known throughout Europe as Abbé Vogler, who also taught Giacomo Meyerbeer and Carl Maria von Weber. When the orchestra transferred to Munich in 1778, Franz initially stayed in Mannheim but eventually rejoined his colleagues in 1783. In 1789, two of his stage works, the singspiel Der Triumph der Treue (Triumph of Loyalty), and the comic opera Der Quasi-Mann (Almost a Man) were performed in Munich. A year later, he married the celebrated singer and pianist Margarethe Marchand, who had received instructions from Leopold Mozart in Salzburg. The newlyweds embarked on an extended concert tour lasting several years before eventually returning to Munich. With his comic operas Mitternachtsstunde (The Witching Hour) and Der Kuss (The Kiss), Danzi finally enjoyed some success as an opera composer, and it secured his appointment as Assistant Kapellmeister. However, the unexpected death of his wife in 1800 significantly “lamed his ambition as a composer,” and when court intrigue and professional jealousies became unbearable, he departed for Stuttgart in 1807. Danzi was employed as music director at the Stuttgart Court Theater, where he met the young Carl Maria von Weber. Highly supportive of Weber’s quest to promote serious German-language opera, the two composers became close friends. Ill health forced Danzi to resign his post in Stuttgart in 1812, and he subsequently took a less strenuous post in Karlsruhe. Although he continued to compose short operas and singspiels, he focused his primary efforts on lending support to Carl Maria von Weber. As such, he produced every one of Weber’s early stage works in Karlsruhe shortly after their respective premieres. Danzi’s health continued to gradually deteriorate and he died on 13 April 1826. In all, Danzi composed seventeen German-language stage works, but only a few have survived the ravages of time. He also composed instrumental music in virtually all the genres then in use. Prominently among them are several bassoon concertos, symphonies and a delightful Concertante for flute, clarinet and orchestra. Today, he is primarily known for his chamber music compositions, in particular his woodwind quintets. His first set, published as Op. 56 in 1821, was not only designed to raise the level of musicianship at the court of Karlsruhe, it also sought to emulate the tremendous financial success Anton Reicha has reaped with his twenty-five woodwind quintets composed in Paris between 1811 and 1820. Danzi skillfully embeds a combination of distinctive instrumental sonorities within a light and entertaining musical texture. He published a second set, his Op. 68, shortly before his death. Danzi lived and worked during a transitional, yet highly significant time in the history of music. He knew and adored Mozart, equally disliked the music of his contemporary Ludwig van Beethoven, and his efforts on behalf of Carl Maria von Weber significantly aided the establishment of serious German Opera. The music critic Friedrich Rochlitz summarized Danzi’s achievements and historical position in his obituary in 1826, “in the great revolution that has occurred in instrumental music during the last decade and that Danzi of course witnessed, recognizing its great results and holding them high, he could not quite appropriate them and even less proliferate them — his works have fallen asleep or are going to their rest with so many other works likewise worthy of respect and very popular in their time.” Danzi’s music is charming, entertaining and a worthy and valuable product of its culture and its time; maybe we should bring it back to life?