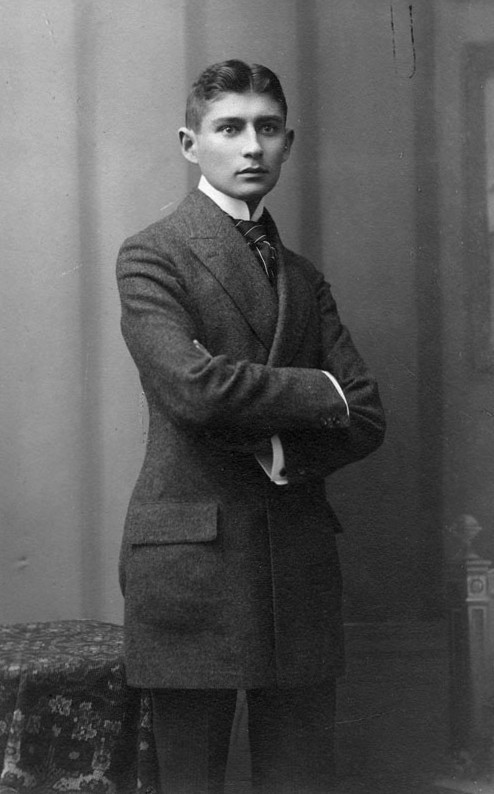

In the pantheon of modern literature, few figures loom as enigmatically as Franz Kafka. A Czech-Jewish writer born in Prague on 3 July 1883, Kafka crafted stories that resonate with a haunting, almost prophetic clarity that captured the anxieties of the modern condition. His works probe the absurdities of bureaucracy, the fragility of identity, and the alienation inherent in human existence.

Franz Kafka, 1910

Franz Kafka published little during his lifetime and died at the age of 40 in 1924. However, his posthumous legacy has cemented him as a cornerstone of existential and modernist literature.

As scholar Stanley Corngold writes, “Kafka’s gift was to make the unsayable speak, to give form to the formless terrors of modernity.” In a world still grappling with absurdity and alienation, Kafka remains not only a literary giant but a guide through the labyrinth of the human condition.

Jan Freidlin: Kafka Sonata (Andreas Hermanski, clarinet; Émilie Fend, guitar)

Between Silence and Screams

Franz Kafka

Born into a middle-class Jewish family in the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s multilingual Prague, Kafka navigated a cultural crossroads where German, Czech, and Yiddish coexisted uneasily. He had a tense relationship with a domineering father, and eventually settled for a career as an insurance clerk.

By day, he grappled with bureaucratic minutiae and by night poured his soul into writing.

This dual existence mirrors the tension in his stories, where ordinary characters confront surreal, oppressive systems.

Kafka suffered from tuberculosis, which ultimately claimed his life. His physical frailty contrasted with the intensity of his intellectual and creative output. Walter Benjamin described this paradox as “a life lived at the edge of annihilation.”

Kafka was engaged multiple times, but never married because he was haunted by fears of intimacy and failure. His diaries and letters reveal a man wrestling with self-doubt, yet they also shimmer with wit and philosophical insight. His private writings “offer a window into a mind perpetually at odds with itself.”

György Kurtág: Kafka-Fragmente, Op. 24 (Anu Komsi, soprano; Sakari Oramo, violin)

The Kafkaesque Universe

Franz Kafka: Metamorphosis

The term “Kafkaesque” has entered the dictionary to describe situations marked by absurdity, oppression, and existential dread. Kafka’s stories are populated by characters trapped in incomprehensible systems, their struggles both deeply personal and universally resonant.

In The Metamorphosis of 1915, Gregor Samsa awakens to find himself transformed into a monstrous insect, a metaphor for alienation. The Trial (1925) and The Castle (1926), both published posthumously, delve into the labyrinthine nature of authority.

Franz Kafka: The Trial

In The Trial, Josef K. is arrested for an unspecified crime, navigating a faceless judicial system that offers no clarity or resolution. Similarly, The Castle follows K., a land surveyor, as he seeks entry into an elusive bureaucratic stronghold. Both novels remain unfinished, as the “narrative ambiguity mirrors the uncertainty of modern life.”

Poul Ruders: Kafak’s Trial (Johnny van Hal, tenor; Gisela Stille, soprano; Marianne Rørholm, mezzo-soprano; Gert Henning-Jensen, tenor; Michael Kristensen, tenor; Johan Reuter, baritone; Hans Lawaetz, bass; Anders Jakobsson, bass; Bo Anker Hansen, bass; Hanne Fischer, mezzo-soprano; Mogens Gert Hansen, tenor; Royal Danish Opera Chorus; Royal Danish Orchestra; Thomas Søndergård, cond.)

Precision of Paradox

Kafka’s prose is deceptively simple, yet its precision and economy amplify its unsettling effect. Milan Kundera notes, “Kafka’s style is like a scalpel, cutting through the surface of reality to expose its absurdity.”

His use of allegory and surrealism invites multiple interpretations, from psychoanalytic readings to Marxist critiques and gendered dynamics, as Elizabeth Boa notes, “female characters often serve as enigmatic mediators between protagonists and oppressive systems.”

Kafka’s influence has extended far beyond literature, permeating philosophy, psychology, and political theory. Jean-Paul Sartre famously remarked, “Kafka is the poet of the impossible, showing us the world as it is when stripped of illusions.” From psychoanalytic critics to reading Kafka as a prophet of totalitarianism, the author’s relevance endures in the 21st Century.

Peter Wiegold: Kafka’s Wound (Will Self, reader; notes inegales; Peter Wiegold, cond.)

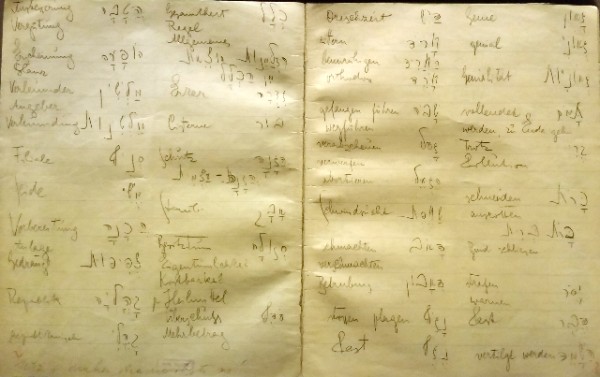

Franz Kafka’s notebook

Confronted with algorithmic governance and existential uncertainty, Kafa’s vision remains acutely relevant. As scholar Mark Anderson observes, “Kafka speaks to our age of faceless corporations and automated injustice, where individuals are reduced to data points.”

His exploration of alienation also finds echoes in contemporary mental health discourse, and Kafka’s cultural footprint is vast. He has inspired adaptations in film, theatre, and the visual arts. His aphorisms, such as “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us,” remain a rallying cry for literature’s transformative power.

Franz Kafka’s genius lies in his ability to distill the ineffable anxieties of existence into stories that are both intimate and universal. His life, marked by personal and cultural tensions, fuelled a body of work that continues to challenge and captivate. In a world still grappling with absurdity and alienation, Kafka remains not only a literary giant but a guide through the labyrinth of the human condition.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Ernst Krenek: 5 Lieder, Op. 82 (Christine Schäfer, soprano; Axel Bauni, piano)