Franz Schubert

We still don’t know exactly where the idiom “Swansong” actually originated, but presently we use it to mean a last effort or final production coming from someone in a respective field before retirement, or sometimes, death. It is probably most familiar to us from the world of sports, “with Kobe Bryant scoring 60 points in his final game, or Peyton Manning winning the Super Bowl in his last season.”

The concept that swans sing a beautiful song just before death has a long pedigree in Western thought, and the Greek philosopher Socrates is credited with saying “Will you not allow that I have as much of the spirit of prophecy in me as the swans? For they, when they perceive that they must die, having sung all their life long, do then sing more than ever, rejoicing in the thought that they are about to go away to the god whose ministers they are.” The proverbial singing swan, used as a metaphor for the final great effort, becomes a much-embraced concept in the arts, literature, and music, as exemplified in the famous madrigal setting by Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625).

The silver Swan, who living had no Note,

when Death approached, unlocked her silent throat.

Leaning her breast against the reedy shore,

thus sang her first and last, and sang no more:

“Farewell, all joys! O Death, come close mine eyes!

More Geese than Swans now live, more Fools than Wise.”

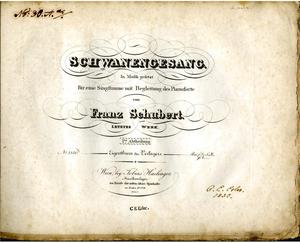

Franz Schubert’s final and horribly painful days in November 1828 included bouts of delirium, requests for novels by James Fennimore Cooper, ceaseless singing and moments of great lucidity when he was working on his compositions. Schubert had been seriously ill for some time, but it’s impossible to tell by the quantity and consistency of his compositions. “In just his final 14 weeks, he wrote his last three piano sonatas, and the heart-melting C-Major String Quintet.” A few short months after Schubert’s death, the Viennese publisher Tobias Haslinger published a group of fourteen Schubert songs composed to texts by three different poets. Wishing to present this publication as Schubert’s final musical testament to the world, Haslinger and Schubert’s brother Ferdinand entitled the collection Schwanengesang (Swansong). Containing some of the greatest Lieder that Schubert ever composed, there is still disagreement about whether or not Schwanengesang is actually a cycle.

Franz Schubert’s final and horribly painful days in November 1828 included bouts of delirium, requests for novels by James Fennimore Cooper, ceaseless singing and moments of great lucidity when he was working on his compositions. Schubert had been seriously ill for some time, but it’s impossible to tell by the quantity and consistency of his compositions. “In just his final 14 weeks, he wrote his last three piano sonatas, and the heart-melting C-Major String Quintet.” A few short months after Schubert’s death, the Viennese publisher Tobias Haslinger published a group of fourteen Schubert songs composed to texts by three different poets. Wishing to present this publication as Schubert’s final musical testament to the world, Haslinger and Schubert’s brother Ferdinand entitled the collection Schwanengesang (Swansong). Containing some of the greatest Lieder that Schubert ever composed, there is still disagreement about whether or not Schwanengesang is actually a cycle.

Franz Schubert: Schwanengesang, D 957 (Hermann Prey, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

Schubert’s Schwanengesang

There are contradictory accounts concerning the origin of Schubert’s thirteen songs with lyrics by Ludwig Rellstab and Heinrich Heine, published together with “Die Taubenpost,” with lyrics by Johann Gabriel Seidl. In the original manuscript in Schubert’s hand, the first 13 songs were copied in a single setting, on consecutive manuscript pages, and in the standard performance order. There is some suggestion that Schubert had intended to publish the settings of Rellstab and Heine separately, as he offered the Heine set of poems to the Leipzig publisher Probst. “Die Taubenpost,” meanwhile, has no connection to any of the first 13 songs and was appended by Haslinger to round out Schubert’s Schwanengesang. Rellstab’s poems passed to Schubert via Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s assistant. It has been suggested “almost every song in Schwanengesang deals with love or it’s absence, linking it to Beethoven’s “An die ferne Geliebte.” The Rellstab set ranges from the singer inviting a stream to convey a message to his beloved in the opening “Liebesbotschaft” (Message of love), to the concluding “Abschied” (Farewell) when the singer bids a cheery but determined farewell to a town he must now leave forever.

Franz Schubert: Schwanengesang, D 957 – No. 9. Ihr Bild (Hermann Prey, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

Franz Schubert: Schwanengesang, D 957 – No. 13. Der Doppelgänger (Hermann Prey, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

The site of Schubert’s first tomb at Währing

Schubert discovered the poetry of Heine only in 1827. He quickly realized the dark, stirring and modern voice of the poet, and probably saw it as the future of the Lied. The Heine set opens with a narrator blaming himself for the sorrow he has to bear, and proceeds to “Ihr Bild” (Her image), in which the singer imagines that the portrait of his beloved has smiled and shed some tears. The final song “Der Doppelgänger,” (The double) finds the singer looking at the house where his beloved once lived, and he is horrified to see someone standing in torment outside; it appears to be none other than himself. Schubert’s choice of poets seems to set up a polarity in the cycle, in which both the past and future of the Lied are showcased. The appended “Taubenpost” (Pigeon Post) is like the epilogue after the drama, and it is the very last song Schubert wrote. “Sehnsucht” (Longing) is the name of the pigeon, which flies out but doesn’t ever come back. It is indeed Schubert’s Swansong, as he “dispenses his love in music without self-pity.”

Franz Schubert: Schwanengesang, D 957 – No. 14. Die Taubenpost (Hermann Prey, baritone; Gerald Moore, piano)

Thanks for the insightful comments. I have transcribed and notated the Jeffrey Benton translation of the songs into English. Very elegant texts. Let me know if you’d like to know more. Best, Kevin Helppie, DMA

Schubert’s ‘In der Ferne’ seeks an assurance of being granted a transit welcome. The recitative flavour is sordid until the traveller., fugitive-like, gains a lyrical respite. Alas, temporarily. Allow a Chinese Hakka to share a similar foretold destiny as someone who has no permanency of abode.

Schuberts ‘ Schwanengesang ‘ is beslist geen cyclus. Een ‘ Schwanengesang ‘ is het wel. En wat voor eentje ! De allermooiste die er bestaat. Daarom een goede keuze geweest van uitgever Haslinger en broer Ferdinand om deze verzameling laatste liederen zo te noemen. Maar een cyclus is het stellig niet. Gelooft u mij !