Frederic Mompou’s music exists in the liminal space between ancient and modern. Nowhere is this more true than his Musica Callada (which roughly translates as ‘Music of Silence’). In many ways, it is his most radically modern work, yet its extreme spareness and slowness suggest ritual and ancient mystery. Mompou referred to his style as ‘primitivista’. Even at his most dissonant, it always feels as if he is rediscovering something primordial – some very early kind of music.

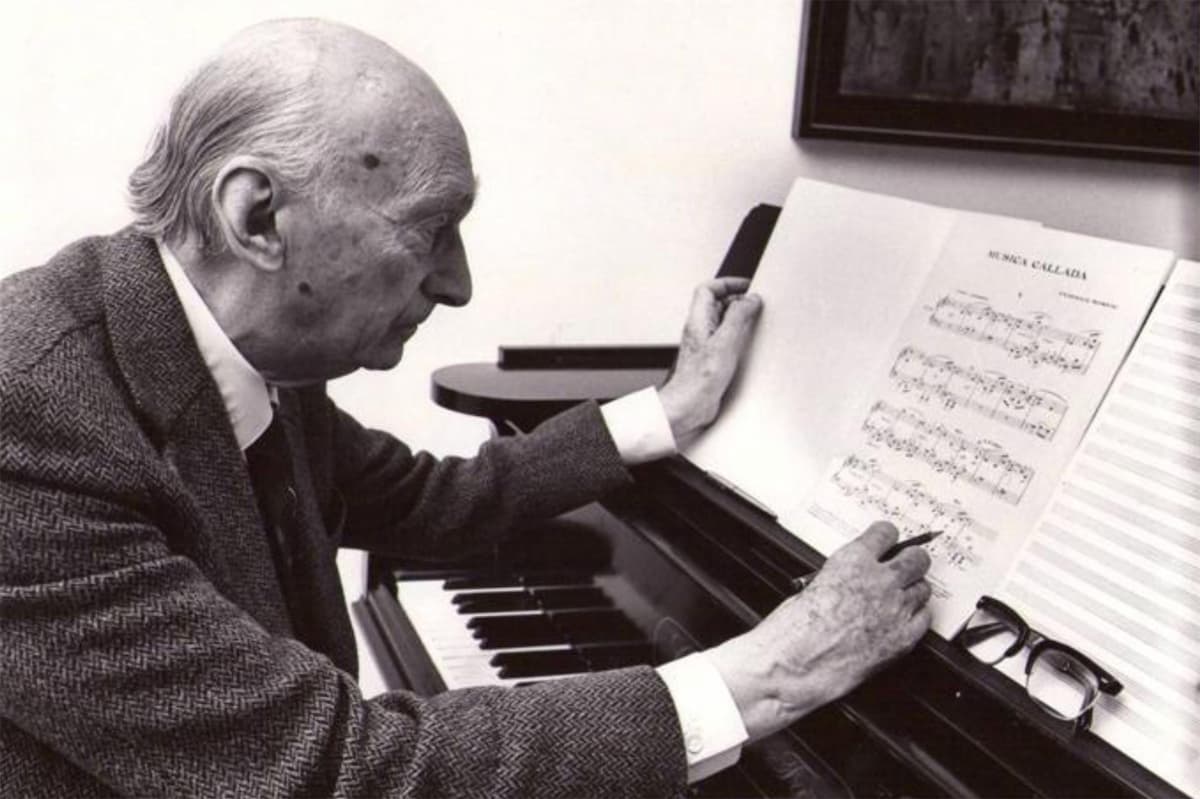

Frederic (Federico) Mompou © kazu-classicalguitar.co.uk

Musica Callada is his magnum opus, consisting of four books and twenty-eight movements. All the movements are relatively short – none are more than three pages of music – and a performance of the entire work only lasts around seventy minutes. Written over nearly a decade, Musica Callada was not conceived as a whole, but rather developed out of separate, smaller works; they were like saplings and seeds that grew independently, and yet together, into a woodland.

Curiously, until Book III none of the movements have end bar lines. There is a sense that the music emerges from, and then gives way to, an infinite silence – but something more like the Japanese concept of silence, ma, which is not an absence of sound but a force and resonance in itself. The other-worldly opening movement, marked ‘Angelico’, does not even have single bar lines. With one exception, it only uses the white notes of the piano, and it has no dynamic marking greater than piano. The music essentially consists of a chant harmonised with close intervals and sevenths that, at a few wonderful moments, open up and transform into a major or minor chord. Although an extreme example, this is nevertheless characteristic of Mompou: he takes a simple melodic idea – sometimes of his own invention, and other times borrowed, such as folk song or chant – and adds slightly strange and often spare harmony.

Federico Mompou: Musica callada, Vol. 1 – I. Angelico (Federico Mompou, piano)

Unusually for Mompou, some pieces in the Musica Callada are almost – though never entirely – without melodic lines. No. 21 could be at first mistaken for a slow movement from Olivier Messiaen’s Vingt Regards sur l’enfant-Jésus: the harmonies are uncannily Messiaen-esque, and the piece makes use of high appoggiaturas reminiscent of birdsong. No. 25 is Mompou at his vaguest, the music fragmentary and economical – like Webern, but more ethereal. We hear so clearly the ‘silence’ to which the title Musica Callada refers – the spaces between Mompou’s reverberant bell-like notes. Nevertheless, in the middle of both pieces melody still finds its way through, for a short time. And to my ears, both movements establish a tonal centre by the end – No. 25 by implication, and No. 21 rather magically, by way of crystalline harmonies using perfect fourths.

Federico Mompou: Musica callada, Vol. 3 – XXI. Lento (Federico Mompou, piano)

Federico Mompou: Musica callada, Vol. 4 – XXV. Quarter Note = 100 (Federico Mompou, piano)

Mompou was exact and perfectionistic, seldom using more notes than was necessary. He would labour over these short works for a long time. The delightfulness of so much of his music comes from its smallness and transparency. What seemed to attract him was more the raindrop than the rain shower, the petal rather than the flower. The result was nearly always an intimate kind of music; his works often feel as if they were written not for an audience, but for one. From his earliest music in the 1910s this style is clear and remained so until the end.

He wrote the overwhelming majority of his music for piano; its bell-like attack and deep but fading resonance particularly suited his soundworld. As a composer of shorter works only for piano – and moreover a composer from Spain, a musical culture on the periphery of the classical tradition – he has remained a fairly obscure figure, even though his work has both an immediacy and a depth that ought to make it as popular as, say, Arvo Pärt’s. (Thankfully, this seems to be changing, with many new recordings of the Musica Callada in particular. I especially recommend Stephen Hough’s album from earlier this year.)

Mompou was also a quiet man, and his music has none of the prestidigitation that easily impresses – the sort of virtuosic effect that is often a kind of captivating trickery rather than real enchantment. Indeed, he is a composer you could never accuse of deliberate cleverness, let alone deceit. His music is childlike in his honesty and clarity – and what a rare and beautiful quality this is.

His lack of cleverness is not a lack of craft or some sole reliance on intuition. Certainly, on the line between intuition and technique which all composers straddle, he leant much more on the intuitive side. This is perhaps why he remained wedded to the instrument with which he was most familiar, the piano. But listen to the last movement (No. 28) of Musica Callada and you find a careful exactness in its voice leading, with inversions gradually moving towards the satisfying conclusiveness of root-position chords. The harmonies become more adventurous and restless in the middle of the movement, but then we are led, almost without realising it, to the noble return of the theme. Mompou knew well what he was doing, and the resulting music has an extraordinary hymnic strength.

Federico Mompou: Musica callada, Vol. 4 – XXVIII. Lento (Federico Mompou, piano)

This triumphant ending changes the whole narrative structure of the work. I find myself comparing it to the gospels, where all the strangeness and ugliness are transformed at the end when we discover that Christ is resurrected. The end becomes a new beginning. That is, it draws our mind back to the beginning as it changes and reshapes all of what we have heard. Mompou himself said that:

“I desire my Silent Music, this newborn child, to bring us a new warmth of life and expression of the human heart, always the same and always renewing itself.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Steven Watson is a classical guitarist, composer and writer in the United Kingdom.