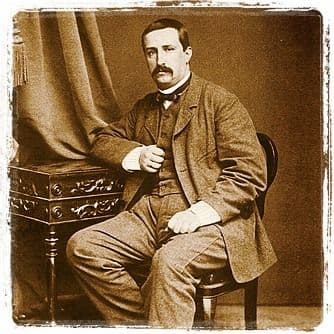

Alexander Borodin (1833–1887). Like many of his fellow composers in mid-century St Petersburg, had a professional career and a side career. Professionally, Borodin was Professor of Chemistry at the Medico-Surgical Academy, and in his spare time, was a composer. This meant that upon his death at age 54, there were many projects left incomplete. Fortunately, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and his pupil, Alexander Galzunov, thought these important enough to complete, Rimsky-Korsakov resigning his professional commission in the navy to take up music full-time.

Alexander Borodin

Borodin wrote 3 symphonies, one under the influence of Mily Balakirev, the most professionally trained of the group of composers known as The Five. The writing of it, always part-time, took him some five years to complete and its premiere in 1868, under the baton of Balakirev, wasn’t exactly great. It took its performance the next year in the first Russian Music Society concert to make its mark. This was Borodin’s first step in extended composition and, although the first movement was judged as quite original, a later critic saw the scherzo movement as being ‘second-hand Berlioz’ and the finale as being ‘second-hand Schumann’.

Alexander Borodin: Symphony No. 1 in E-Flat Major – I. Adagio (Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Stephen Gunzenhauser, cond.)

The third movement was another indication of the greatness in Russian music we would expect to see in the later Borodin.

Alexander Borodin: Symphony No. 1 in E-Flat Major – III. Andante (Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra; Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond.)

The second symphony took even longer to complete, having been worked on for seven years, and was interspersed with the composer’s attention being diverted by the opera Prince Igor. Now Borodin has gotten out of his German / French style and moved into a thoroughly Russian mood. The symphony shows the real development of the composer’s skills, due in part to his work on Prince Igor.

The first movement has dramatic statements in the lower strings, which the composer, in a letter to the critic Vladimir Stasov, said represented a gathering of Russian warriors. Within the basic symphonic framework, Borodin has found a way to be technically novel. The ‘indomitable ostinato’ theme at the beginning and the following cello theme that follows both serve to drive the movement forward. The return of the ostinato coda has been equated with the ‘rhythmic tramplings of Le sacre du printemps’.

Alexander Borodin: Symphony No. 2 in B Minor – I. Allegro (Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Stephen Gunzenhauser, cond.)

The third symphony, which exists in only two movements, consists only of a Moderato Assai and a Vivo. The first movement, Moderato Assai, was largely reconstructed by Glazunov both from Borodin’s sketches and from the string quartet that he had intended it for. Glazunov also had to recreate from his memory of having heard the work played because Borodin had lost the exposition second. The Vivo is a scherzo movement that Borodin had first experimented with as a string quartet some five years earlier, but which lacks a trio section.

Alexander Borodin: Borodin: Symphony No. 3 in A Minor (unfinished) (orch. A.K. Glazunov) – I. Moderato assai (Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra; Gennady Rozhdestvensky, cond.)

For a part-time composer, Borodin brought an elegant Russian sensibility to his work, once he was able to leave his imitations of his German and French models behind. His work on Prince Igor, especially the Polovtsian Dances, which went beyond being a thrilling dance finale to the second act to being a stand-alone work.

Polovstian Dances in Prince Igor

A Google Doodle honoured him in 2018 on his 185th birthday.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter