Easter in Moscow © angelfire.com

Franz Liszt famously proclaimed that instrumental music attempting to communicate or carry meanings, messages or concepts that originate from outside music itself, do need to carry a narrative or descriptive program in order to be understood. This program, essentially a preface or title to a piece of instrumental music, directs the listener’s attention to the poetical idea of the whole or to a particular part of it. What is essential to our understanding of program music then, is not how successfully music imitates musical or non-musical sound, but how it approaches the relationship between representation and expression. Program music therefore seeks to be understood in terms of its program and derives its movement and logic from the subject it attempts to describe. Essentially, it puts the listener emotionally in the same frame of mind, as could the objects themselves. Liszt’s theoretical foundations of “Program Music” extended its influence well into the 20th-century, and stood at the core of a variety of symphonic works that were concerned with the formation of a national, cultural and/or ethnic identity.

For Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908), program music provided not merely a novel means of artistic or nationalist expression. His Russian Easter Festival Overture, composed between 1887 and 1888, combined his gift for brilliant orchestration with a heightened interest in Eastern culture. This particular concert overture was part of a series of dazzling orchestral showpieces that also included the Capriccio Espagnol and Scheherazade. Dedicated to the memories of Modest Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov aimed to reproduce “the legendary and heathen aspect of the holiday, and the transition from the solemnity and mystery of the evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious celebrations of Easter Sunday morning.” In essence, Rimsky-Korsakov musically encoded his childhood memories, growing up in Tikhvin, in Novgorod province. Korsakov remembers the celebration of Easter — also called “Bright Holiday” in Russia — as a large gathering of “people from every walk of life, with several popes conducting cathedral service…the old liturgical chants and nearby monastery bells ringing out.”

For Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908), program music provided not merely a novel means of artistic or nationalist expression. His Russian Easter Festival Overture, composed between 1887 and 1888, combined his gift for brilliant orchestration with a heightened interest in Eastern culture. This particular concert overture was part of a series of dazzling orchestral showpieces that also included the Capriccio Espagnol and Scheherazade. Dedicated to the memories of Modest Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov aimed to reproduce “the legendary and heathen aspect of the holiday, and the transition from the solemnity and mystery of the evening of Passion Saturday to the unbridled pagan-religious celebrations of Easter Sunday morning.” In essence, Rimsky-Korsakov musically encoded his childhood memories, growing up in Tikhvin, in Novgorod province. Korsakov remembers the celebration of Easter — also called “Bright Holiday” in Russia — as a large gathering of “people from every walk of life, with several popes conducting cathedral service…the old liturgical chants and nearby monastery bells ringing out.”

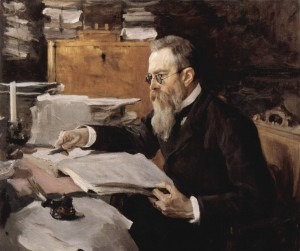

Rimsky-Korsakov © Wikipedia

The Russian Easter Festival Overture is entirely based on chants used in the Orthodox Church. The contemplative opening, evoking the martyrdom and mystery of Good Friday sounds the chant “Let God arise.” Mimicking the throaty incantations and chanting of the popes in quintuple meter, the chant continues to grow in intensity throughout the work, eventually being sounded by the trombone. Pizzicato strings prepare for the great proclamation of Easter, and the timpani introduce another chant quotation. Rhythmically intense “An angel wailed” contagiously spreads to the other instruments in the orchestra. Sparkling with orchestral virtuosity and instrumental luxuriance it musically imitates the Christian ecstasy of the Russian Easter. Finally, amid the trumpet blasts and bell tolling during the triumphant coda, we hear the chant “Christ has risen from the dead.” Powerful climaxes delineate individual sections in a composition of “masterful lucidity, exquisite melodies and intoxicatingly rich orchestration.” In deference to Franz Liszt, Rimsky-Korsakov suggested, “a great deal in my music is not mine.” Be that as it may, the Russian Easter Festival Overture nevertheless captures the unique spirit of Russian culture and music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Russian Easter Festival Overture, Op. 36 (Seattle Symphony Orchestra; Gerard Schwarz, cond.)

One of my first LP’s was Stokowski’s collection of Russian orchestral music. This piece, as Emily Dickenson has said, blew the top of my head off. That was in the 1950’s. I followed a long and clex path to Russian Orthodoxy, converting in 1998. Lors happened in between, but my journey began with tid piece. The joy of the Pascha Service is unbelievable. I’m glad you liked Rimsky-Korsakov’s pice, too!