The Birth of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony

When he started work on his second symphony, Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) started with a funerary idea. After a performance of Carl Maria von Weber’s comic opera Die drei Pintos, which Mahler had completed from surviving sketches, he went home and staged his own funeral. Lighting candles and surrounding his bed with flowers received after the performance, Mahler lay in bed and imagined himself on his funeral bier. His new one-movement work was to be called Totenfeier (Funeral Rites).

Gustav Mahler: Totenfeier (Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; Vladimir Jurowski, cond.)

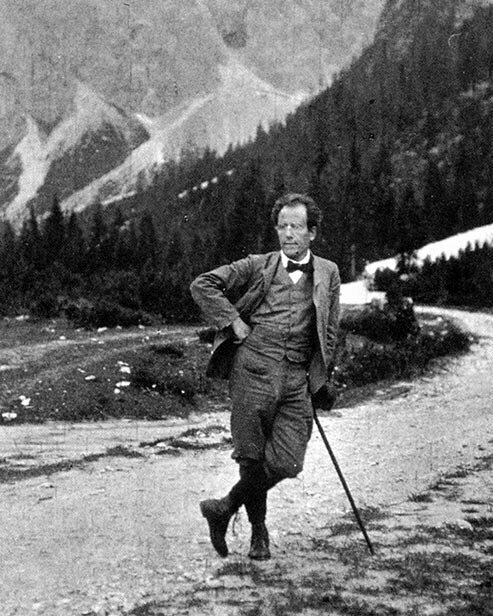

Gustav Mahler

Rethinking this idea, he developed a parallel title of Symphony in C minor. He also abandoned the idea of this as a one-movement symphonic work and started developing the slow movement. He played Totenfeier for Hans von Bülow, a resident of the city of Hamburg and the principle symphonic conductor in town, and he hated it, considering it not even music.

Rethinking the work again, he was inspired by a collection of anonymous German folk poetry that had been collected by Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano as Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn) and published between 1804 and 1808. One of the songs he set was Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt (St. Anthony of Padua’s Sermon to the Fish), which became the inspiration for the Scherzo movement of his nascent symphony. The finale came to him after attending the funeral of Hans von Bülow in February 1894. Hearing the choir sing Friedrich Klopstock’s Die Auferstehung (Resurrection Ode), Mahler took the poetry, expanded it, and used it for the final movement – the culmination of passing from death to eternal life.

Following the development of the final movement, Mahler added another movement in as movement 4. Urlicht (Primordial Light) becomes a haunting prequel to his apocalyptic visions of the Last Judgment in the last movement.

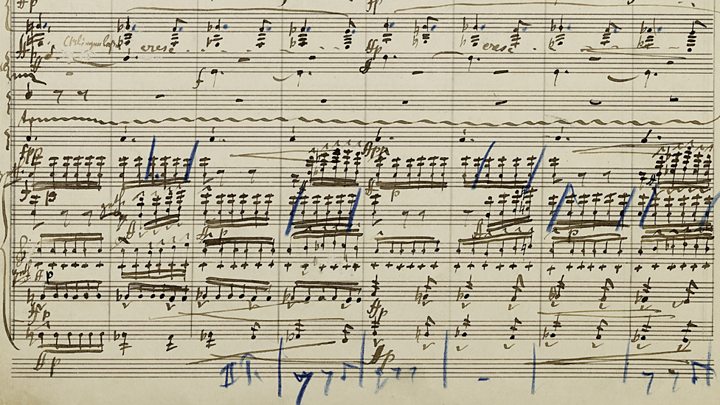

Autograph manuscript of the symphony

In creating his second symphony from all these different sources, Mahler finally transcended the normal symphonic ideas and created music that works in opposition: grim pessimism matched with tentative aspiration. In its first production, the symphony was performed without the vocal movements but within a year, a complete performance was staged.

Mahler was asked to provide a program for the work and we start again at a funeral bier. In the first movement, we stand by a coffin of a beloved friend and think back on his feelings, his struggles, and his aspirations. Our introspection leads us to think about the nature of life and death and the nature of a future life.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, “Resurrection” – I. Allegro maestoso. Mit durchaus ernstem und feierlichem Ausdruck (Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Antoni Wit, cond.)

The next three movements are like intermezzi – happy times in the life of the dead man are recalled as are the happy days, now lost, of his youth. The 3rd movement scherzo is our low point. The Scherzo, for all its merriment and its playful character, it is in fact a deeply pessimistic analysis of the futility and meaninglessness of life.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, “Resurrection” – III. In ruhig fliessender Bewegung (Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Antoni Wit, cond.)

The 4th movement is an answer of faith. The final movement brings the final trumpet to summon the dead to judgement and yet it is the final chorus, to Klopstock’s text, that returns us to a message of love and forgiveness. Here is where the true Resurrection message comes to us.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, “Resurrection” – V. Im Tempo des Scherzos. Wild herausfahrend (Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra; Antoni Wit, cond.)

The second symphony was the first work to bring Mahler his first true recognition during his lifetime. It was his most frequently performed symphony and was also one of his personal favourites: he conducted it regularly until one year before his untimely death, and it was heard at special occasions such as his departure from Vienna, at Carnegie Hall in New York and finally in Paris.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Like the symphonies of Beethoven, their greatness makes it impossible to choose a favorite. All the Mahler symphonies are great masterpieces that are remarkable in their grandeur, beauty, complexity, and the development of symphonic sound. Mahler and Strauss were great conductors who understood the potential for expansion and development of the orchestra. They were innovative masters of the late Romantic period in music.

Mahler’s 2nd Symphony is my favorite piece of any music – next to his 8th, of course!!