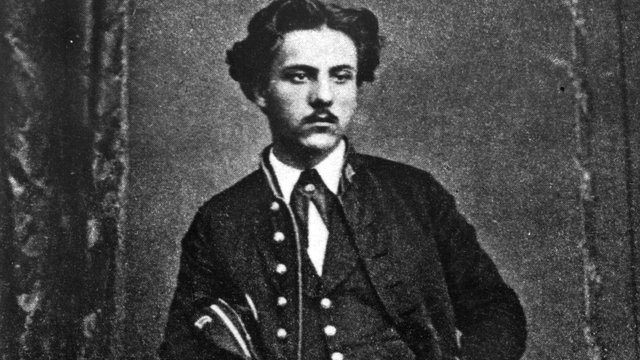

Gabriel Fauré

A good many commentators consider Gabriel Fauré the “greatest master of French song.” He composed stylish and elegant melodies, etched with sleight-of hand urbanity. His music flows effortlessly, “magically combining Monet’s liquid cool with the warmth of a Pisarro landscape.” Fauré was a meticulous and emotionally reserved figure of exquisite taste, who managed to compose music that is nobly restrained and beguilingly sensual at the same time.

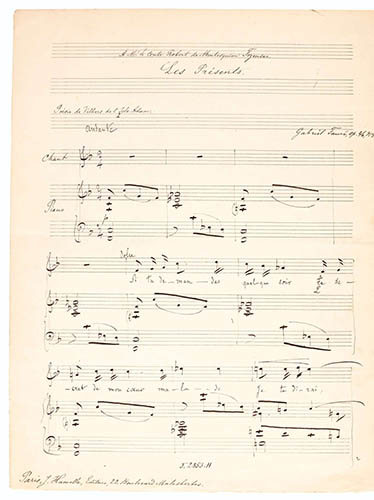

Fauré: Les présents, Op. 46 No. 1

In his mélodies, we don’t find great stories of drama or extravagant passion, but immaculately crafted scores full of grace and tranquility. Fauré’s melodies run like a silver thread through his entire oeuvre, and identify—broadly speaking—the evolution of his style as a composer. Initially we find a young salon charmer whose romances and songs are influenced by his student days at the École Niedermeyer and his close friendship with Camille Saint-Saëns. His association with Pauline Viardot and her daughter Marianne resulted in songs possessing a decidedly Italianate character. Be that as it may, the most successful songs of his youth are directly inspired by the form of the poem.

Fauré: Le papillon et la fleur, Op. 1, No. 1 (Elly Ameling, soprano; Dalton Baldwin, piano)

Fauré: Tristesse, Op. 6, No. 2 (Gerard Souzay, baritone; Dalton Baldwin, piano)

Fauré: 3 Songs, Op. 7: No. 1. Après un rêve (Gerard Souzay, baritone; Dalton Baldwin, piano)

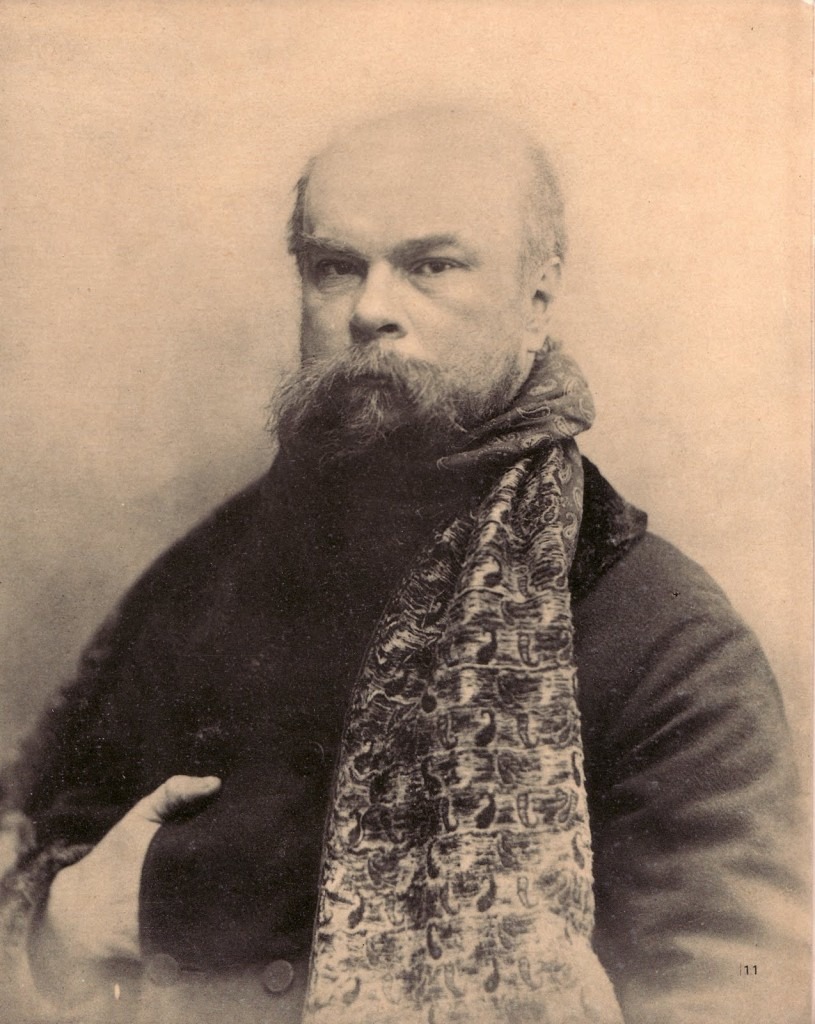

Paul Verlaine

Publishers have basically grouped Fauré’s songs into three collections, dating from 1879, 1897 and 1908, respectively. During his development into a mature master of ever-deepening musical experimentation towards the end of the century, Fauré broadened the scope of his melodic invention. But what is more, he gave novel structure to his song cycles. His setting of poems by Verlaine relies on a dual organization, one that is literary by selecting and arranging the poetry to form a story. Secondly, the music throughout the cycle is based on the use of recurrent themes. That particular harmonic and formal novelty found in La bonne chanson is said to have shocked Saint-Saëns and even intimidated the young Debussy. “The expressive power, the free and varied vocal style, and the importance of the piano part seemed to exceed the proper limits of the song.” In his boldest pieces, like the familiar Clair de lune, Fauré already anticipates the experimentations of his late style.

Fauré: Clair de lune, Op. 46, No. 2 (Jacques Herbillon, baritone; Theodore Paraskivesco, piano)

Charles van Lerberghe

In La chanson d’Ève, a sequel and extension of La bonne chanson, composed between 1906 and 1910, Fauré was looking for some advanced means of unifying the song cycle. Based on poetry by Charles van Lerberghe, it is Fauré’s longest song cycle. The poet describes his vision of Eve as “ a feminine soul, very sweet, very pure, very tender, very dreamy, very wise and at the same time very voluptuous, very capricious, very fantastic.” In his musical setting, “Fauré’ abolishes original sin from the Garden of Eden and forces us to imagine Eve’s relation to the world anew. “Unredeemed because never guilty, Eve does not transcend the world through personal immortality but rather returns to the world, is absorbed by it, becomes it.” The composer is creating a symbolic and musical arc by reducing the number of recurrent themes to two, and pays special attention to a concentrated vocal style. In addition, he infuses the piano accompaniment with a previously unknown polyphonic richness.

Fauré: La chanson d’Ève, Op. 95

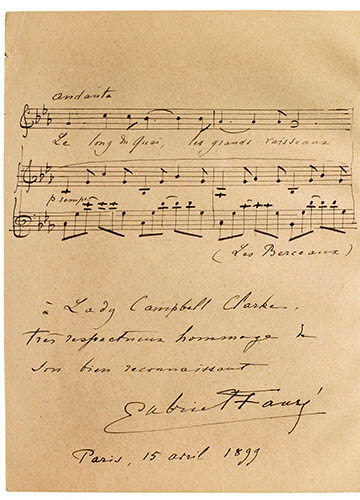

Fauré: Les berceaux, Op. 23 No. 1

In his last three song cycles, Fauré forgoes the idea of common musical themes. Instead, renouncing luxuriance, he is searching for a unity between subject and atmosphere. In fact, the metrical structure of the verse achieves a fine balance with melody, harmony and polyphony. Fauré chose his texts for their flexibility and for a lack of reference to sound, as he felt that such visual descriptions might actually restrict him. He frequently commented that his aim “was to convey the prevailing atmosphere rather than detailed images in poems of this kind.” In that way, Fauré could easily adapt the text to his melodic inspiration, and as is well known, he frequently took great liberties with the verse structure. However, his musical settings are highly sophisticated, as melodic curves coincide with the unfolding of the poem, or as syntax and melody develop continuously to create forward momentum. Striving towards total simplicity, the inscrutable sage Fauré composed music that remains challenging to this day.

Gabriel Fauré: L’horizon chimérique, Op. 118 (Jonathan Lemalu, baritone; Roger Vignoles, piano)