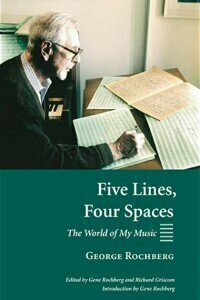

“Five Lines, Four Spaces”

As a composer and teacher George Rochberg (1918-2005) strongly believed that “music should express the passions of the human heart.” A robust proponent of serial techniques in the mid-1960s, Rochberg eventually sought new expressions by returning to traditional romantic and post-romantic values. “There can be no justification for music,” he writes, “if it does not convey eloquently and elegantly the passions of the human heart…The insistence on ignoring the dramatic, gestural character of music, while harping on the mystique of the minutiae of abstract design for its own sake, says worlds about the failure of much new music.”

As a composer and teacher George Rochberg (1918-2005) strongly believed that “music should express the passions of the human heart.” A robust proponent of serial techniques in the mid-1960s, Rochberg eventually sought new expressions by returning to traditional romantic and post-romantic values. “There can be no justification for music,” he writes, “if it does not convey eloquently and elegantly the passions of the human heart…The insistence on ignoring the dramatic, gestural character of music, while harping on the mystique of the minutiae of abstract design for its own sake, says worlds about the failure of much new music.”

George Rochberg: Three Elegiac Pieces, No. 1

100 years ago, George Rochberg was born in Paterson, New Jersey. He took piano lessons and eventually became interested in jazz and composition. After gaining a degree from Montclair State Teachers College, Rochberg enrolled at the Mannes School of Music in New York and counted George Szell as one of his teachers. Returning from active military service, Rochberg entered the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia in 1945 and studied composition with Gian Carlo Menotti. A Fulbright scholarship accorded him the opportunity to study with Luigi Dallapiccola in Rome, and by 1951 Rochberg became an editor of the music publisher Theodore Presser in Philadelphia. His first major works are stylistically modeled on Hindemith and Bartok, and George Szell with the Cleveland Orchestra premiered his Second Symphony.

George Rochberg: Symphony No. 2

The work immediately attracted critical attention and a recording contract. By 1960, Rochberg became chairman of the music department at the University of Pennsylvania, but the premature death of his son Paul forced a complete reevaluation of his artistic compass. “Modernism ended up allowing us only a postage-stamp-sized space to stand on, and we cut the rest away,” he wrote.

Rochberg and Solti

George Rochberg: 3rd String Quartet (excerpt)

Following the premiere, Donal Henahan wrote in The New York Times, “The appeal of the work, and on one hearing it seems certain to have lasting value, lies not in any literary stance but its unfailing formal rigor and old-fashioned musicality. Mr. Rochberg’s quartet is—how to put this—beautiful.”

But not everybody was happy, and much heated and hateful commentary appeared in conservatories and music journals. In his music and his writings on music, Rochberg firmly declared serialism “finished, hollow, and meaningless.” Clearly, this put in question the most scared of all modernist dogmas, “the necessity of the stylistic revolutions of the 20th century.” Fiercely critical of modernism’s misplaced notion that music could break cleanly from its own history, Rochberg “exhibited an honesty and courage that transcended all differences of ideology.”

But not everybody was happy, and much heated and hateful commentary appeared in conservatories and music journals. In his music and his writings on music, Rochberg firmly declared serialism “finished, hollow, and meaningless.” Clearly, this put in question the most scared of all modernist dogmas, “the necessity of the stylistic revolutions of the 20th century.” Fiercely critical of modernism’s misplaced notion that music could break cleanly from its own history, Rochberg “exhibited an honesty and courage that transcended all differences of ideology.”

George Rochberg: Violin Concerto

Rochberg had strong views on the excesses of modernism, but he always maintained that every composer must find his own voice. “I reserve the right to compose 12-tone music in the future–or any other music I choose. I’ve tried very hard to rid myself of that stultifying conception of historical line, and if I want to contrast dissonant chromaticism cheek by jowl with a more accessibly tonal style, I will do so. All human gestures are available to all human beings at any time.” Rochberg died in 2005 at the age of 86, and the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, Switzerland holds the vast majority of his compositions.