Joyce Di Donato as Cherubino (Met Opera)

In some cases, the vocal problem comes from changing audience taste. Beginning with the very first operas, including Monteverdi’s Orfeo of 1607, male singers with unchanged voice, i.e., castratos, had roles, including, it is thought, that of Orfeo’s beloved, Euridice. By the late 17th century, and for another century, the male lead was a high-voiced male. If there wasn’t a role for a castrato, the opera was probably going to be a failure.

But, in the modern world, castratos singers are non-existent and we still want to hear these operas. With the new found popularity of Handel’s operas, and the fact that most of the lead male roles were for castratos, we’re faced with two choices: write the music down in pitch so that a tenor can sing it, or cast a woman in the role. In both cases, we’re changing what the composer has given to us.

Now the question of difference between a castrato singing and a woman singing the same role is interesting: in one case, we have a defunct voice type sung with all the strength of a man’s voice, but which is as high in pitch as a soprano. On the other, we have a woman singing at pitch, but without the male strength behind it. The two were never equal. And, even today, the male high-voice singers such as countertenors do not match the sound world of the castrati. The combination of male strength and unchanged voice isn’t matched by male strength and falsetto voice today. In addition, the vocal range of a countertenor is that of a mezzo-soprano or contralto, not a soprano.

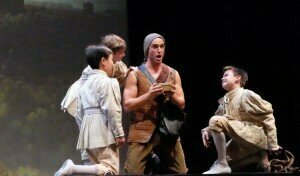

John Brancy as Papageno surrounded by sprits (Clarion Music Society) Photo by Hope Lourie Killcoyne

Handel: Serse (Xerxes), HWV 40, Act I: Frondi tenere e belle … Ombra mai fu, “Largo” (Carlo Bergonzi, tenor; Austrian Radio Symphony Orchestra; Paul Angerer, cond.)

Handel: Serse (Xerxes), HWV 40, Act I: Frondi tenere e belle … Ombra mai fu, “Largo” (Jochen Kowalski, counter-tenor; Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Chamber Orchestra; Hartmut Haenchen, cond.)

Handel: Serse (Xerxes), HWV 40, Act I: Frondi tenere e belle … Ombra mai fu, “Largo” (Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Les Arts Florissants; William Christie, cond.)

Three very different sounds for the same character – an unusual situation in opera today, but a common problem in dealing with operas of the 17th and 18th century.

Carrying the situation forward, we have roles that are boy characters but which are always sung by women. In Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, the servant Cherubino, who attempts through the opera to learn about women and who is eventually packed off to the army, is played by a soprano. In Act I, Cherubino is a boy played by a woman. In Act II, Cherubino dresses up like a girl thus giving us a boy playing a girl, played by a woman.

In Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier, The Marschallin’s young lover, Octavian, is a role for a mezzo-soprano. Strauss cast a woman in the role because he felt that a tenor voice would sound wrong for the part. In this production, Anne Sofie von Otter plays the young Octavian and Felicity Lott the Marschallin (start at 05:41).

Zolina Ngejane as Pamina surrounded by spirits (Isango Ensemble, South Africa)

In the second act, Pamina, fearing that Tamino’s silence means he has cast her off, contemplates suicide, but the three spirits dissuade her.

In this performance, the Three Spirits are played by young boys, with their attendant thin voices (at 2:15:32)

Here we hear how the stronger women’s voices put the music across better.

The decisions made by the composer can be changed by the decisions made in casting, and for us, the audience, the result may be quite different than intended. As a listener, you need to make your own decision about what you want to hear when you’re confronted with this situation: a lost voice or a better substitution.

You treat the origin of castrati oh so delicately, e.g., “…young men with unchanged voices…”, “…male singers with unchanged voice, i.e., castratos, …”. You do not define the term castrato. A castrato was a prepubescent male who was blessed or cursed with an outstanding voice. He was castrated to keep his voice from changing. A recent BBC article goes into some detail on the subject while also exploring the growing demand for counter tenors. The relevant part is about mid-way through the article.

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20160404-the-fascinating-phenomenon-of-men-who-sing-high

Most of the star castratos were actually altos, not sopranos, and so their roles should be sung by baritones, not tenors. If they are sung with original bel canto technique by a baritone they will sound much better than the necessarily non bel canto technique of counter tenors.