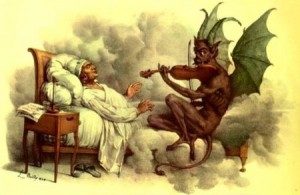

“One night I dreamed I had made a pact with the devil”

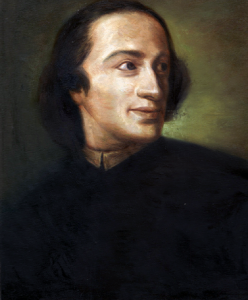

Giuseppe Tartini

His playing was renowned for its combination of technical and poetic qualities, and Italians proclaimed him “the finest musician in the world.” He also made a pact with the devil for his soul, and the “Devil’s Trill Sonata,” represents “a triumph of imagination which has never left the repertory.” Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) died in the year of Beethoven’s birth, 250 years ago in Pirano, then part of the Venetian Republic, now part of Slovenia.

Basilica St. Anthony Padua

Destined for a monastic career, he rejected his father’s wishes and enrolled as a law student at Padua University. According to contemporary accounts, Tartini devoted most of his time to improving his fencing and to the study of music. His secret marriage to the niece of the Bishop of Padua—I tell you more about that in an upcoming love article—necessitated his flight to Assisi. Locked away in a convent, he devoted himself to the study of the violin for at least three years. Forced to support himself, he became an itinerant violinist playing in the orchestra of the Ancona and also the Fano opera house.

Interior St. Anthony Padua

Tartini eventually established himself in Venice and came under the influence of the famed violinist Francesco Veracini, who was the head of the Venetian Academy of Music. Deeply impressed by Veracini’s playing, Tartini once again withdrew for several years of solitary study to explore the principles of violin playing. A good many of his technical and acoustic discoveries and elucidations served as the “basis of every violin school in the world.” In 1721, Tartini was appointed as director of the orchestra at the Basilica of St. Anthony at Padua. The terms of his contract granted him the freedom to perform internationally, and we find him taking part in performances in Parma, Bologna, Camerino, Ferrara, and Venice. He also spent three years in Prague, initially connected to a performance for the coronation of Emperor Charles VI.

Tartini’s The Art of Bowing

However, since a Venetian innkeeper accused him of fathering her recently born child, Tartini was in no hurry to return to Italy. Ill health obliged him “against his will,” to return to Padua in 1726. His first published works were issued in Amsterdam, and he was repeatedly invited to appear in France, Germany and England. He declined all invitations, and a stroke suffered in 1740 partially paralyzed his left arm. From then on he devoted less time to playing and composing, and focused almost exclusively on theoretical matters. His noted bowing study “L’Arte del Arco” was published in Naples during his lifetime, and after nearly fifth years of service to Parma, he died there on 26 February 1770.

Giuseppe Tartini: Violin Concerto in C Major, D. 12 (Federico Guglielmo, violin/cond.; L’Arte dell’Arco)

Louis-Léopold Boilly: Tartini’s Dream (1824)

Tartini principally composed in two instrumental genres, the solo violin concerto with string accompaniment and the violin sonata. We know that he had been asked to write music for the opera house in Venice, but he always refused because “the human throat is not a violin fingerboard.” To this day, no satisfactory edition of Tartini’s music has been issued, principally because the composer returned over and over to his original manuscripts of finished works and added and/or deleted whole sections. In some cases he moved entire movements from one place or one piece to another. In essence, Tartini produced successive versions of the same piece, and he steadfastly refused to append dates to his musical autographs. On the other hand, we have a much clearer picture of Tartini the music theorist. Over his lifetime he accumulated a large library on music, philosophy, religion and mathematics. He engaged in serious studies of the principles of acoustics, and published his discoveries in 1754. His treatise on ornamentation was even translated into French, and his famous letter to Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen explained in great detail the bowing practices of the time.

Tartini began his teaching activities after his return to Padua from Prague, establishing his violin school “Scuola di Nazioni” in 1728. As he was internationally famous, a great many students flocked to Padua, including the well-known violinists Pugnani and Nardini. Students were taught not only violin technique but also composition, with a course of study usually lasting two years. Apparently, he paid careful attention to each individual student, accepting only nine disciples in 1737. His teaching method was focused on “clarity of execution and intonation, beauty of sound, and subtlety of expressive nuance.” Much of his teaching was based on “the mastery of the bow,” and his legacy made its way outside Italy as well. Leopold Mozart’s “Violinschule,” for one, copies the first part of Tartini’s treatise on embellishments in translation. Alongside Vivaldi and Veracini, Tartini was one of the greatest violinists of the 18th century, and he has rightfully been referred to “as the godfather of modern violin playing.”