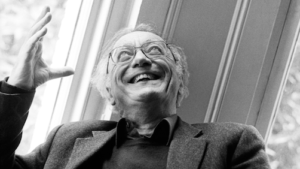

Alfred Brendel is one of the reasons why I play the piano. My mother was a great fan of Brendel, and my love of Schubert’s piano music, especially the Impromptus and Moments Musicaux, is the direct result of my mother hearing Brendel play this repertoire in concert. A few days after the concert, she presented me with an Edition Peters score of the music and urged me to learn it. I was only 11 or 12 at the time…

Brendel has been a hugely respected figure on the global piano scene for as long as I can remember, and his retirement from performing in 2008 (appropriately, for an artist who has focussed on the composers of that city, in the golden hall of the Musikverein in Vienna) was met with many generous plaudits tinged with sadness at the end of a great, music-filled career; he had been performing for some 60 years. He preferred not to continue to perform until his faculties or physical health deteriorated. So, there was no farewell tour, just a single concert, and the manner of Brendel’s retirement is perhaps typical of an artist who is intensely self-contained and a very private man.

Brendel has been a hugely respected figure on the global piano scene for as long as I can remember, and his retirement from performing in 2008 (appropriately, for an artist who has focussed on the composers of that city, in the golden hall of the Musikverein in Vienna) was met with many generous plaudits tinged with sadness at the end of a great, music-filled career; he had been performing for some 60 years. He preferred not to continue to perform until his faculties or physical health deteriorated. So, there was no farewell tour, just a single concert, and the manner of Brendel’s retirement is perhaps typical of an artist who is intensely self-contained and a very private man.

It takes a lot of imagination to bring a work alive but it is on the terms of the compositions and not on the terms of showing off. It is not possible without you, but I am responsible to the composer and particularly to the piece – Alfred Brendel

He is a musician whose intellectual curiosity and rigour has continually fuelled his understanding and appreciation of the music he plays. He is a great researcher and autodidact, an eloquent writer, who pursues parallel interests in art, literature, poetry and philosophy which undoubtedly feed his musical landscape. He was one of the first pianists of the modern era to perfect “intellectual” music making, and embraced the model of the thinking musician rather than one driven by emotion. For some, this has resulted in playing which is rather cool; Brendel may not be a risk-taker in performance, but his greatness perhaps lies in his impeccable taste and musical integrity, founded on a very deep understanding of the music in all its structure, nuance and variation, and the expressive effect of these formal qualities.

If I belong to any tradition, it is the tradition which makes the masterpiece tell the performer what to do, and not the performer tell the masterpiece what to do.

Alongside this, his evident affection for the music he plays enhances our own experience and appreciation of it. A communicator in his craft, he always manages to convey mood, be it wit and humour in Haydn, rhetoric and despair in Beethoven, or the bittersweet nostalgia of late Schubert. (Perhaps one of Brendel’s greatest achievements has been to raise the profile of Franz Schubert, a composer who, without Brendel’s, advocacy would probably still be regarded as the poor relation to Beethoven.)

He has avoided the usual channels to success with a stubborn wish to carve his own career path, avoiding the aura of celebrity which surrounds other artists, and allowing his musical development to mature at his pace and on his own terms. Thus, his reputation is almost entirely built upon his impeccable playing rather than the effect of marketing or powerful record companies.

He has avoided the usual channels to success with a stubborn wish to carve his own career path, avoiding the aura of celebrity which surrounds other artists, and allowing his musical development to mature at his pace and on his own terms. Thus, his reputation is almost entirely built upon his impeccable playing rather than the effect of marketing or powerful record companies.

At 20, I had no fanatic urge to be great. I knew that I had potential and wondered how far it could be taken by the time I was 50. (interview with the New York Times, 1981)

It is the Viennese masters – Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert – with whom Brendel feels the greatest kindship and to whom he has paid the most scrupulous attention, but it is worth observing that he started his career in the 1950s with notable performances of Prokofiev (Piano Concerto n°5), Stravinsky (Petrushka), Mussorgsky (Pictures of an Exhibition), and, in the sixties, Chopin. As for those composers with whom he is now most closely associated, when one considers the huge variety and complexities of their writing, his repertoire seems very broad indeed: Haydn’s Piano Sonatas, the complete piano sonatas of Mozart and Beethoven, not to mention his Piano Variations, Concertos, and Cello Sonatas; Schubert’s Piano Sonatas; Schumann’s Piano Concerto, Kreisleriana, the Fantaisie op. 17, Fantasiestücke, Kinderszenen. Then there are his acclaimed recordings of Liszt – the Concertos, Totentanz, Malediction, Années de pèlerinage, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses; plus works by Brahms, Busoni, Berg, Schoenberg….. Between 1958 and 1964 Brendel became the first pianist to record the complete piano works of Beethoven.

Liszt: 2 Légendes, S175/R17 – No. 2. St. Francois de Paule marchant sur les flots

Fortunately, Alfred Brendel has not disappeared from the music scene. A regular in the audience at London’s Wigmore Hall where he listens to and supports other musicians, he now has more time to mentor younger pianists such as Kit Armstrong (Imogen Cooper and Paul Lewis are amongst his more senior proteges). He also gives readings of his poetry and stimulating lectures on subjects such as Schubert’s last sonatas, ‘Light and shade in interpretation’ , ‘Does classical music have to be entirely serious?’, and debunking the image of Franz Liszt as a showman and charlatan, his thoughtful erudition tempered by wit and good humour. And for those who miss his presence on the concert stage, his fine, extensive catalogue of recordings remains.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

I totally agree, I have not heard another musician analyze music as profoundly and universally as he does. Bravo Alfred!!!

Brendel is Mozart for me, or Beethoven. The most faithful genius of the contemporary pianist. He is responsible for the exquisite hours of my delight listening sonatas from the great composers. Fortunately, I own a lot of his CD’s recordings.