Gustav Klimt, 1914

In 1903, the Austrian painter and illustrator Gustav Klimt paid a visit to Ravenna, the capital of Byzantine Italy in the 6th century. The proclaimed goal of this visit was to broaden his range of artistic historical references by closely examining Byzantine mosaics that graced the interiors of both sacred and secular buildings. This technique of decorative art that combined small pieces of glass, stone or other materials to create patterns and pictures against a predominantly golden background, sparked, upon his return to Vienna a creative explosion.

In his so-called “Golden Period” Klimt incorporates his recently gained experiences into his allegorical and portrait paintings, embodying the highly erotic, psychological and aesthetic preoccupations of turn-of-the-century Vienna’s dazzling intellectual world. Klimt’s decorative mosaic style borrowed contours and shapes from Egyptian and Mycenaean sources and combined them with gold elements incorporated in a lustrous and iconic background. The subjects themselves became one with the glowing surroundings. While parts of his subjects emerge three-dimensionally, the space in which they are placed is projected into a framed and freely flowing plane. To perfect the harmony of space and material, that is, between the psychological exterior and interior worlds, Klimt employed the plane as a psychological aid in the process of dissecting space. “Suggesting formal flexibility and extenuating an ambiguous opposition of space and plane, he places the focus on the ornament and texture as advertisement and message.”

Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Violin Sonata in G Major, Op. 6

Portion of Klimt’s painting Medicine

Gustav Klimt was born in Vienna in 1862, into a lower middle-class family of Moravian origin. His father worked as an engraver and goldsmith, and his mother “had an unrealized ambition to be a musical performer.” Klimt was awarded a scholarship to study architectural painting at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts in 1876. Initially, Klimt revered Hans Makart, the foremost history painter of the time, and he readily accepted the principles of conservative training. Together with two brothers and their friend Franz Match, they formed the “Company of Artists” in 1880 and received numerous commissions to paint murals and ceilings in large public buildings. In 1886, the painters were asked to decorate the Viennese Burgtheater, “effectively recognizing them as the foremost of decorators of Austria.” Completing the work in 1888, Klimt received the Golden Order of Merit from Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria, and he also became an honorary member of the University of Munich and the University of Vienna. Klimt was considered one of the leading artists of his day, and in high demand as a portraitist. An art historian writes, “Paradoxically, it was at this point, with a fabulous career as a classicist painter unfolding before him, that Klimt began turning towards the radical new styles of the Art Nouveau.”

Johannes Brahms: Four Piano Pieces, Op. 119 (Paul Lewis, piano)

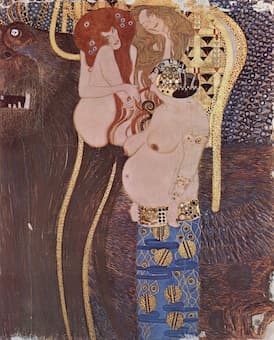

Portion of Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze

In 1894, Klimt was commissioned to create three paintings to decorate the ceiling of the Great Hall of the University of Vienna. His three paintings, Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence were immediately criticized for their radical style and called “pornographic.” The painter had transformed traditional allegory and symbolism “into a new language that was more overtly sexual.” The public outcry came from all walks of life, political, aesthetic, and religious, with the result that the paintings were never displayed. In fact, German forces burned all three paintings in May 1945. Klimt was not alone in his opposition to the traditional Austrian artistic establishment of the time. In 1897, together with forty other notable Viennese artists, Klimt resigned from the Academy of Arts and founded the “Union of Austrian Painters,” more commonly known as the “Vienna Secession.” Klimt became the president of the organization with the aim of providing exhibitions for unconventional young artists, to bring the works of the best foreign artists to Vienna, and to publish its own magazine. In 1902, Klimt finished the Beethoven Frieze in celebration of the composer, which was directly painted on the walls of the Secession building.

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 15 in A Minor, Op. 132 (Hagen Quartet)

Klimt: Schubert at the Piano

By 1910, Klimt had moved past his Golden Style, and in one of his last pictures in that style “Death and Life,” he changed the original golden background to blue. Klimt worked at home, normally wearing sandals and a long robe with no undergarments. He avoided café society, and his fame “usually brought patrons to his door, and he could afford to be highly selective.” Klimt died on 6 February 1918 in Vienna, having suffered a stroke and pneumonia due to the worldwide influenza epidemic of that year. Klimt embodied a type of modernism that still holds fascination today. As an artist he left his mark, especially on Vienna, “and he played a crucial role in shaping the era around 1900 together with his companions, among them Josef Hoffmann, Otto Wagner, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Richard Gerstl, Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka.” Together with Paris, Munich, and London, Vienna was a European intellectual center. The fields of visual arts, literature, music, architecture and science experienced a heyday, with new and groundbreaking ideas emerging at a pace and density rarely encountered before. Working against the interior of the previous century, that is the ideas, the moods and the gestures of pathos that permeated Vienna, Klimt sought to realize modernism by inventing a new style through the external form of objects. His expressions placed equal value on the content and its presentation, and the atmospheric frame undertook the same task of communication as the content it encased. As such, “the oeuvre of Gustav Klimt mirrors the artistic path from the historicist “Ringstrasse era” to the beginnings of abstract art in a particularly unique manner.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Richard Strauss: Four Last Songs